The Hitchhiker’s Guide to Investment Research, Part 3: Time is Money

So far in this trilogy, I have addressed the need to focus on what really matters for investment success instead of what some theory says should matter. I also showed how any given theory can stop working as the world and the behaviour of people changes. It is this second phenomenon where many strategists and economists as well as investors in general can fall into the trap of becoming stubborn.

Take for instance the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). I told you I would get back to that. This theory (or model) of how capital markets work assumes that one can summarise the interactions of billions of people in financial markets with one linear variable: the systematic risk of a security vs. the market portfolio.

The empirical evidence against the CAPM is overwhelming and has been known for a long time. James Montier has summarised much of it in his all-time great CAPM is Crap note. Yet, many investment practitioners continue to use the CAPM in determining allocations and expected returns of stocks and other investments. If only you make this tweak to the CAPM here or define the market portfolio like this, the CAPM starts to work again, they say. Don’t believe me? Look here for a 2022 example.

By now, several hundreds of violations of the CAPM in the real world have been documented. We call them ‘factors’ and the factor zoo has become so overpopulated that it has created its own problems. I was originally trained as a mathematician and physicist and if there ever was a theory or model in physics that was violated hundreds of times in experiments, physicists would long have abandoned that theory. But in finance, many people still use the CAPM.

And if a theory or model doesn’t work in practice, they tell you to just wait and collect more data. Eventually, it will work. This is the argument that I get most often from monetarists when it comes to forecasting inflation based on a theory that has stopped working three decades ago, but also from strategists who use the CAPM to ‘forecast’ returns.

The problem is that in practice when we invest money, most people don’t have the luxury to accumulate losses for years and decades before they may or may not be proven right. In the investment world, time is indeed money.

Jeremy Grantham loves to rant about career risk, that is the risk that your investments turn out correct, but you have to wait so long that you lose all your clients or your money before you are proven right. I am not talking about the famous adage that markets can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent. Even in a rational market without exaggerations, a theory or model can stop working for a long time.

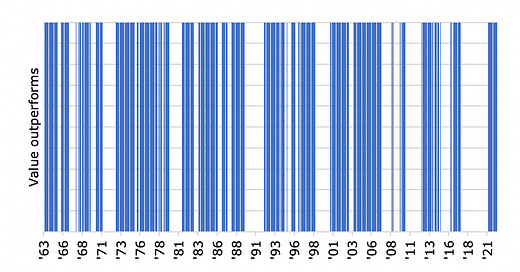

Take a look at the chart below. The top graph shows the 12-month periods when value stocks outperformed growth stocks and the bottom graph shows the 12-month periods when momentum worked and stocks with strong past performance outperformed stocks with weak past performance. We know from this study that value and momentum are the two factors with the strongest empirical evidence that they do work. These are among the very few factors that are above suspicion for both practitioners and academics. Yet, if you look at the last 20 years, you can see how periods of value outperformance became less frequent, and the wait time until value worked again became longer and longer.

12-month periods of value (top) and momentum (bottom) outperformance

Source: Liberum, Ken French Database

How did value investors fare over the last 20 years? Not well if you look at their assets under management. According to my calculations, equity value funds lost some 20% to 30% of their starting assets in the three years from 2019 to the end of 2021. Even now that value has started to outperform again do we see larger outflows out of value funds than growth funds in the UK and Europe. Investors have given up on value stocks and after a long period of underperformance they won’t come back that quickly.

Yesterday, I showed how equity markets started to react very differently to macroeconomic news after the financial crisis when interest rates went down to zero. The experimental evidence I showed was based on some six years of data, but by now it has expanded to some 12 years of data. If your job is to help people make money and your forecasts turn out to be wrong for a decade, it doesn’t matter if you are eventually proven right. By the time your theory starts working you will have lost most of your clients or your money.

So, whenever someone tells me that his theory or model is going to be right in the long run, I go somewhere else. Career risk is a real thing and while I would love to only have clients with infinite patience, the reality is that one can only use models and theories that work within a manageable time frame. I had a computer science professor at university who said that in practice it doesn’t make a difference if a computer can never perform an action or if the user has to wait five minutes for the computer to finish the calculations. The same holds for the world of finance and investments.

Don’t take this as a call for short-termism, though. I am against short-termism. The trick is to let the real world guide you and rely on data to tell you what the market is doing over reasonable time frames. Focus on very short time frames like days or hours and you are likely to follow the noise, not the signal. Focus on extremely long time frames like decades and you are going to be right, but also out of a job.

Oh, and don’t ever try to match the data to the model. If the data contradicts your theory, it is time to abandon the theory or adjust the theory to the data. In practice, too many strategists and economists do the opposite and try to ignore data that doesn’t fit the data. But nature, as Richard Feynman wisely said, cannot be fooled.