Long-time readers of these missives will know that I am fascinated by the long-term memory of societies and how things like the German aversion to debt and fear of inflation have become cultural traits. The fascination started with the seminal Depression Babies study by Ulrike Malmendier and Stefan Nagel and has since been fuelled by many additional papers. So, forgive me for going off that tangent once again. Still, as Germany embarks on a Zeitenwende of using larger deficits to finance defence and infrastructure spending, the ghosts of inflations past once again haunt my fellow Germans…

Research on the long-term effects of inflation and other major economic shocks has so far almost exclusively focused on the difference between people who experienced the shock and people who didn’t. People who were alive during the Great Depression were more afraid of inflation and taking financial risks than people who weren’t, even some 70 or 80 years later.

But nobody is alive in Germany today who has first-hand experience with the Weimar hyperinflation of 1922 and 1923. All that is left is a collective memory of the event. So, no matter who you ask in Germany, they should, on average, be equally sensitive to inflation.

Alas, a fascinating study shows that you can still trace the Weimar hyperinflation in today's attitudes towards inflation and financial decisions. To show this, the researchers exploited local differences in the severity of the Weimar hyperinflation across Germany. Here is a beautiful map of the average inflation between 1920 and 1924 for each zip code (!) in modern-day Germany.

Local inflation in the 1920s by today’s German zip code areas

Source: Braggion et al. (2025)

Here is the relationship between local inflation a hundred years ago and the inflation expectations of Germans living in these areas today. A 10% increase in local inflation from 1920 to 1924 is associated with a 0.4 percentage point increase in inflation expectations today.

Local inflation and today’s inflation expectations

Source: Bragggion et al. (2025)

The memories of the 1920s persist in Germany at a very granular level. Indeed, they have become part of the local folklore. The researchers show that migrants who live in different areas show a significantly smaller effect size. Their inflation expectations today are much less sensitive to the local inflation during the Weimar hyperinflation than native Germans.

But they are not entirely free of this effect. Indeed, analysing speeches of members of parliament mentioning inflation shows that politicians from areas where local inflation was higher in the 1920s today emphasise the threat of inflation more than politicians from other areas.

In short, the Weimar hyperinflation is transmitted within German households from generation to generation, influencing public discussion and perception of inflation threats today.

This spills over to financial decisions. People who lived in areas with higher local inflation in the 1920s still had a higher savings ratio and invested substantially less in stocks and bonds.

But what caught me by surprise was when they checked for robustness. Typically, these checks are boring because the authors repeat the same exercise with other variables. But I didn’t expect how they did the robustness checks in this case.

One possible explanation for the local variation in inflation concerns the local economic dynamism or levels of wealth. The first chart shows that local inflation in the 1920s was particularly high in the south of Germany. These areas are today the richest and economically strongest regions of the country. Plus, they tend to be politically more conservative, which in Germany is deeply linked with being more conservative on fiscal matters such as the aversion to debt and deficits.

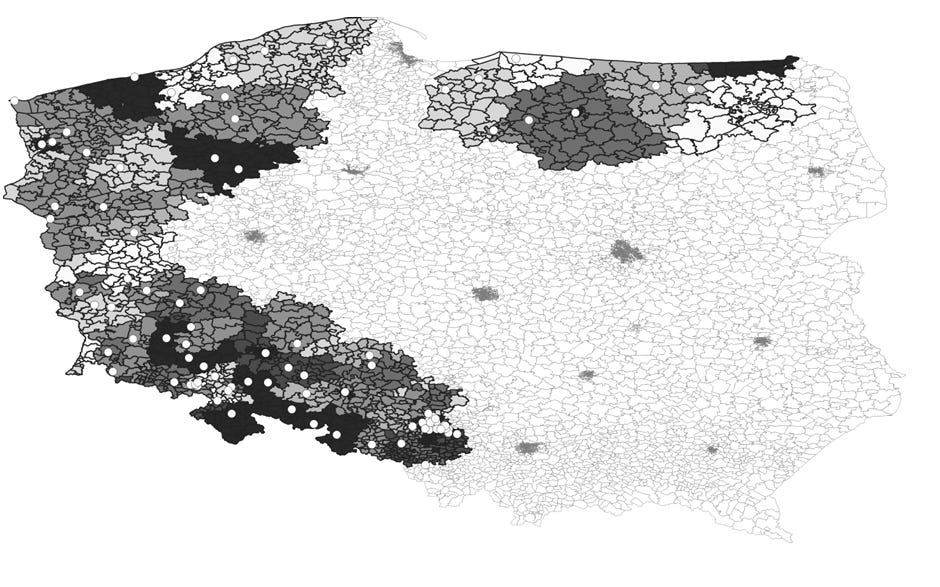

To test that this did not spoil the results, the researchers went abroad. Germany in the 1920s was much larger than it is today (and let’s not talk about what caused that loss of land…). So, they checked the local variation in inflation expectations of people in Poland who live in former German areas. I was pretty surprised to see that there is almost the same fear of inflation and increased inflation expectations in regions of Poland that experienced higher local inflation in the 1920s compared to the rest of the country.

They say that history teaches us that we don’t learn from it. Well, Germans seem to be unable to unlearn their history.

Local inflation in the 1920s of former German territory in Poland

Source: Braggion et al. (2025)

This is really interesting analysis. I wonder if there is any effect cause though by the displacement of people after the war, plus the effects of immigration and how the demography of Germany has changed overall since the 1920s. It’s a great case study on collective memory at a local level but I wonder how much those localities have changed over the last hundred years.

fascinating! I had no idea the cultural aversion to inflation is so strong in now-Polish Silesia and Pomerania.

It all fits the theoretical structure of cultural materialism à la Marvin Harris, whereas culture follows economic structure and circumstances, and not vice-versa.

I would assume there is another variable, though. Hyperinflation in Germany was coupled with extreme social unrest and societal dysfunction. Ian Kershaw has written tomes about how the murder rate increased exponentially in Germany in the 1920s, to levels unparalleled anywhere in the world nowadays. I suspect e.g. Turkish folks who knew hyperinflation don't have the same degree of engrained collective aversion as Germans did.