We all would want analyst ratings and recommendations to be objective. But alas, analysts are humans, too, and that means they exhibit all kinds of biases in their recommendations. One of the latest biases to be documented is that analysts are like bad teachers: they rate on a curve.

Rating on a curve, the practice where a teacher or an analyst provides an assessment not based on absolute merits but on the relative merit of each subject relative to the pool, is not helping anyone. In schools and universities, it means that an unqualified student can graduate with flying colours just because the rest of the year has been even dumber. And with equities, it can mean that among a peer group of pigs, the one wearing lipstick will get a ‘buy’ rating.

But according to new research, that seems to be happening in equity markets all the time. Think about it this way. In an ideal world, an analyst should provide a buy/hold/sell rating in absolute terms or relative to the sector average.

For simplicity, let’s assume these ratings are only driven by the valuation of a company. Then the company with the lowest valuation in a sector should be a buy while the company with the highest valuation should be a sell (at least relative to the sector). In absolute terms, the stocks may all be buys or sells depending on the valuation level of the stocks in the sector.

But hardly any analyst can cover all the stocks in the sector. Typically, they only cover a selection of stocks. This selection of stocks covered by the analyst influences the rating each stock gets.

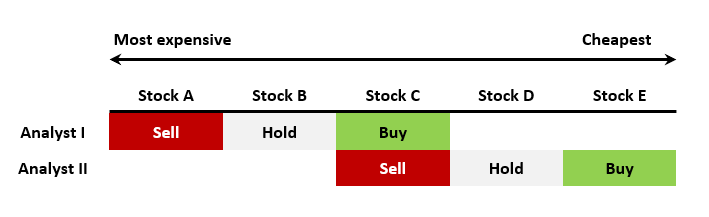

To see how this works, assume the sector consists of five stocks and two different analysts cover three stocks each. Assume further that stock A is the most expensive one, then stock B, stock C, down to the cheapest stock E.

What happens when analysts grade on a curve?

Source: Bhattacharya et al. (2024)

Because Analyst I covers the three most expensive stocks in the sector, stock C looks like it is the cheapest in his coverage. Hence, if the analyst grades on a curve, stock C looks like the one-eyed among the blind and gets a better rating than stocks A or B.

Compare this with analyst II who covers the three cheapest stocks in the sector. From his perspective, stock C is the one-eyed among a group of people with 20-20 vision, so he may give stock C a worse rating than stocks D and E. The result is that stock C gets a buy rating from analyst I and a sell rating from analyst II.

That’s really not helpful for investors, because to understand the rating, each investor needs to be aware of the entire universe the analyst covers. And obviously, most investors aren’t able to do that.

So, what can one do? The good news is that as analysts get better at their job and gain more experience, this bias is reduced. Hence, as investors, we may want to put more emphasis on top analysts and analysts with more experience covering a sector rather than the up-and-coming analysts.

Problem solved: substitute analysts with gpt4-o