Most people know that after the financial crisis, banks were hit by tighter capital requirements, which has been blamed by some for the decline in bank lending. But a new study shows that (i) this decline in bank lending started much earlier, and (ii) the main driving force behind it was the rise of shadow banking.

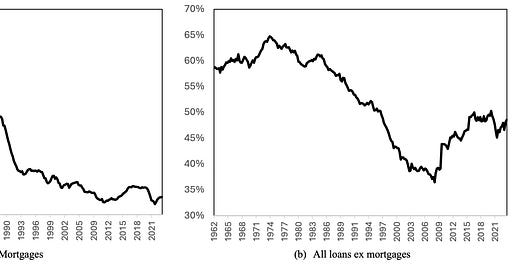

Between 1970 and 2023, the share of total loans made by US banks and recognised on their balance sheets dropped from 60% to 35%. This drop has been particularly large in the mortgage space where mortgages backed by the US government have become available. This means that most mortgages in the US today are issued with some form of government agency backing, and banks have little incentive to issue mortgages that cannot be pushed off their balance sheets. But even if we look at bank lending ex-mortgages we see that the share of loans held on banks’ balance sheets has dropped significantly.

Bank balance sheet lending as a share of total lending

Source: Buchak et al. (2024)

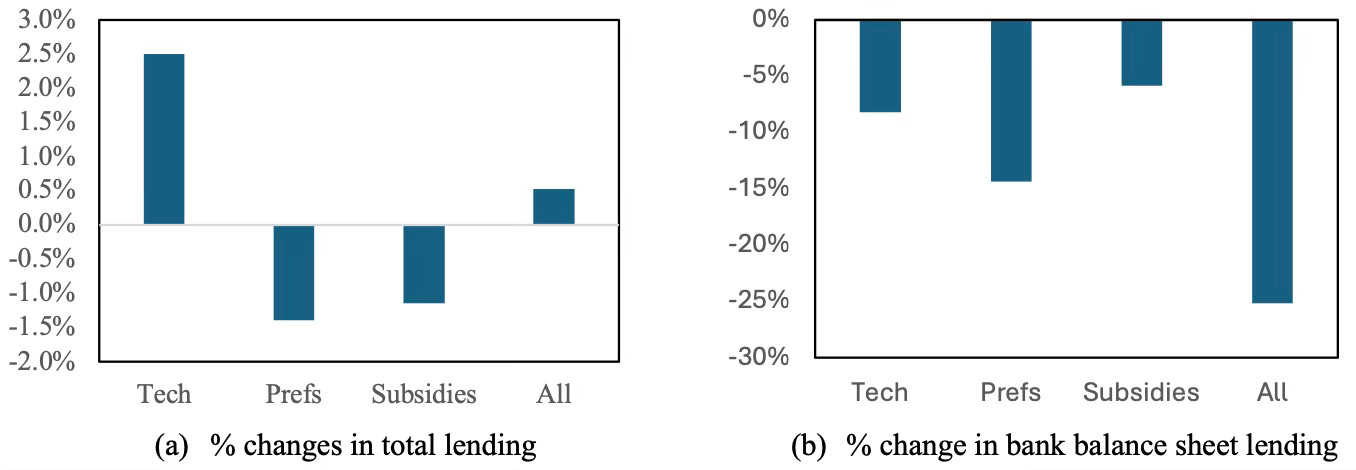

Where it gets interesting, though, are the two charts below. They show the results of estimates in the study of what change has been driven by one of three forces:

Technological progress in securitisation of debt and the rise of the shadow banking system.

Changing saving behaviour by households which have reduced bank deposits in favour of money market and securities with money market-like structure.

Change in capital requirements for banks holding loans on their balance sheet.

As you can see in the left-hand chart, technological advances and the rise of shadow banking have led to an overall increase in total lending activity in the US. But less and less of that is done by banks in the form of traditional on-balance sheet loans. Instead, about half the decline in on-balance sheet lending has been driven by a secular decline in deposit holdings while one-third was due to the rise of shadow banking solutions and only a small part (about a fifth) is a reaction to higher capital requirements.

Drivers of change in total lending (left) and balance sheet lending (right)

Source: Buchak et al. (2024)

This brings me to an important point that is simply not discussed enough in my view. We are focusing so much on bank regulation and are constantly monitoring the quality of bank loans and mortgages. But more than half of all loans are now held outside of bank balance sheets and a large part of these loans is in the shadow banking system, held by hedge funds, pension funds, and others. And there is almost no regulation or oversight of these instruments. Heck, there is hardly any data available on how much of that stuff is around and where it is held. We have no idea what is going on with these loans and if there are any problems with them. The best data I know comes from Chapter 2 in the recent Financial Stability Report of the IMF which shows how prevalent and leveraged private debt loans are in the US

It feels to me like we are still trying to fight the last war of the financial crisis of 2008 while the real crisis will come from a part of the economy that is as opaque and unmonitored as any I have come across in my career.

I suspect, without any evidence whatsoever, that after 2008 a lot of "money" shifted from lending and investing (different parts of the capital stack) into unregulated sectors in a search for better opportunities, both higher reward and less regulated. ("Money" here I define as entities that collect cash and then have to deploy it. e.g. Pension funds, Insurance Companies, Hedge Funds, etc. I'd include retail traders, but I think they mostly went the crypto routes.)

I agree with Joachim that these unregulated areas hold the greatest risk for a future crisis. We don't know the levels of leverage being employed, and we don't know how a domino type failure will, or if it will, impact the regulated markets. The primary purpose of most financial regulation is to prevent normal economic and business cycles from effecting systemic destruction crises. When a significant portion of capital deployment (50%???) evades regulation, it means the odds of systemic failures are maybe twice as high when the inevitable next business or economic cycle panic occurs.

Standard risk management requires you to calculate, or estimate the likelihood of an adverse event, and then the likely loss associated with the event. Economic reversals (panics, crashes, etc.) have a reasonably predictable probability. But if we have no transparency or regulation of the systems, we can't get a handle on the size of the loss if an event occurs. You can take a SWAG, but that's about it. Leverage is the gasoline on the fire.

There is probably more regulation than you think. A large part of direct lending exposure is take on by insurers, which you dont mention as an asset class. This is usually in mandates with rules that limit the portfolio managers in terms of the risk they can take. In the US, insurers will not take on these loans without an external rating (and the mandate will prescribe a minimum rating). In Europe, the insurers take on unrated loans but specify other limits such as leverage limits and interest coverage limits. In each market, the insurance regulators pay a lot of attention to the loan asset class.