Cyclical companies should have higher returns in the long run than defensive companies. At least if markets price the risk of a company being more exposed to the business cycle, I expect returns on cyclical stocks to be higher. But how much higher exactly? And how should one identify cyclical stocks?

Will Goetzmann from Yale and Akiko and Masahiro Watanabe from the University of Alberta came up with a deceptively simple approach to measuring the cyclicality of US stocks: they regress the excess return over the market of each stock on the stocks market beta and the forecast GDP growth from the Livingston Survey of professional forecasters. In short, they add consensus GDP forecasts as a second factor to a simple CAPM.

As the charts below show, this makes all the difference in the world. A simple CAPM cannot explain any variation in stock returns, which is just a reiteration of what everyone already knows. But with GDP forecasts added to the regression, 71% of the variation in return between stocks is explained.

Forecast returns vs. realised returns in the CAPM (left) and CAPM plus GDP forecasts (right)

Source: Goetzmann et al. (2024)

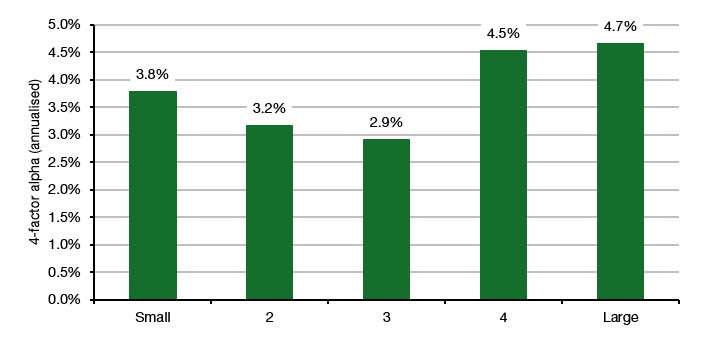

And when one sorts stocks based on size and their sensitivity to GDP forecasts, one can see that the stocks that are most sensitive to GDP outperform the stocks that are least sensitive. The chart below shows the difference in returns between the 20% stocks most sensitive to GDP and the 20% stocks least sensitive to GDP for different sizes. All data is outperformance per year after adjusting for the usual four factors of market beta, value, size, and momentum. What I find particularly interesting is that this outperformance of cyclical stocks is stronger for large caps than small caps, which is the opposite of what normally happens in these tests.

More cyclical stocks outperform less cyclical stocks, particularly for large caps

Source: Goetzmann et al. (2024).

But it’s not just large caps that show pronounced outperformance for cyclical stocks. The largest sensitivity and outperformance can be seen for value stocks. The most beaten down stocks with the cheapest valuations and largest GDP-dependence show the highest outperformance in the long run.

More cyclical stocks outperform less cyclical stocks, particularly for value stocks

Source: Goetzmann et al. (2024).

So now you know what to buy. Cyclical stocks with low valuations. Then hold on to them for a long time. This is really the hard part because value investing is already psychologically demanding, but value investing in highly cyclical companies is a step up from that.

Would be interesting to know what their universe of cyclical stocks is. Wondering if their methodology ireveals that they might not be exactly what we generally think they are…

That would presumably mean now, buy gold miners