Last week, I explained why the oft-cited criticism that “ESG investing is investing with additional constraints and must thus lead to sub-optimal outcomes” is a red herring.

But there is another argument, ESG critics often use to claim that ESG investing must be inferior to conventional investing. It is the argument that in equilibrium, brown stocks and sin stocks must have higher returns than green stocks or ethical stocks. I oversimplify a little bit, but the argument goes something like this: If more and more investors invest in green stocks and underweight or divest from brown stocks, the valuation of these brown stocks will drop. Eventually, the valuation of these shunned stocks will become so low and the risk premium on these stocks will become so high that they will start to significantly outperform green stocks.

If an investor just holds on to his or her oil and gas stocks for long enough, they will be handsomely rewarded as ESG investors abandon the market creating a significant risk premium for these stocks.

Again, there is a lot of truthiness to this argument. In fact, it is a correct argument if the assumptions made in the argument hold true. And there are two crucial assumptions in this argument that, in my view, are debatable. Let’s look at them based on the example of fossil fuel stocks.

The first assumption is that the companies that issue these stocks (i.e. oil and gas companies) are a going concern and continue to generate positive cash flows in the future. This is not at all a given. History is full of these value traps. When horses were replaced by cars, the makers of horse carriages became incredibly cheap investments. When the railways were replaced by the airplane, many railroad companies became deep value. When the housing crises hit in 2008 many mortgage lenders like Countrywide became very cheap indeed.

That is not to say that these companies will go under wiping out investors. What happens when you have a structural shift in the economy is that many companies seize to be a valid proposition as a going concern and will go bankrupt. Other companies will survive but because of the structural shifts, they will never recover to the same level as before the shift. In the year 2020, we don’t have listed companies that are specialised in making horse carriages, but we still have listed railroad stocks. Yet, they are so small that an investor who stuck to railroads in the wake of the shift to airplanes will never recoup his losses.

I don’t think that the oil & gas industry as a whole will go extinct. Even in the year 2100, we will have global oil & gas companies. But with the structural shift away from fossil fuels towards renewable energy sources their cash flows will permanently decline and as a result, many of today’s oil & gas companies will go bankrupt and those that survive will be permanently smaller than in the past.

Arguing that brown stocks will command a risk premium and thus higher returns than green stocks assumes that the economy of the future is practically the same as the economy today. And that seems highly unlikely to me.

The second assumption of the argument that brown stocks should eventually outperform green stocks is that there is a more or less stable equilibrium in markets. In essence, the argument assumes that there are no flows of assets between ESG investors and conventional investors. I have a lot of sympathy for this argument as a long-term steady state. But let’s take a look at the current reality rather than an idealised steady-state.

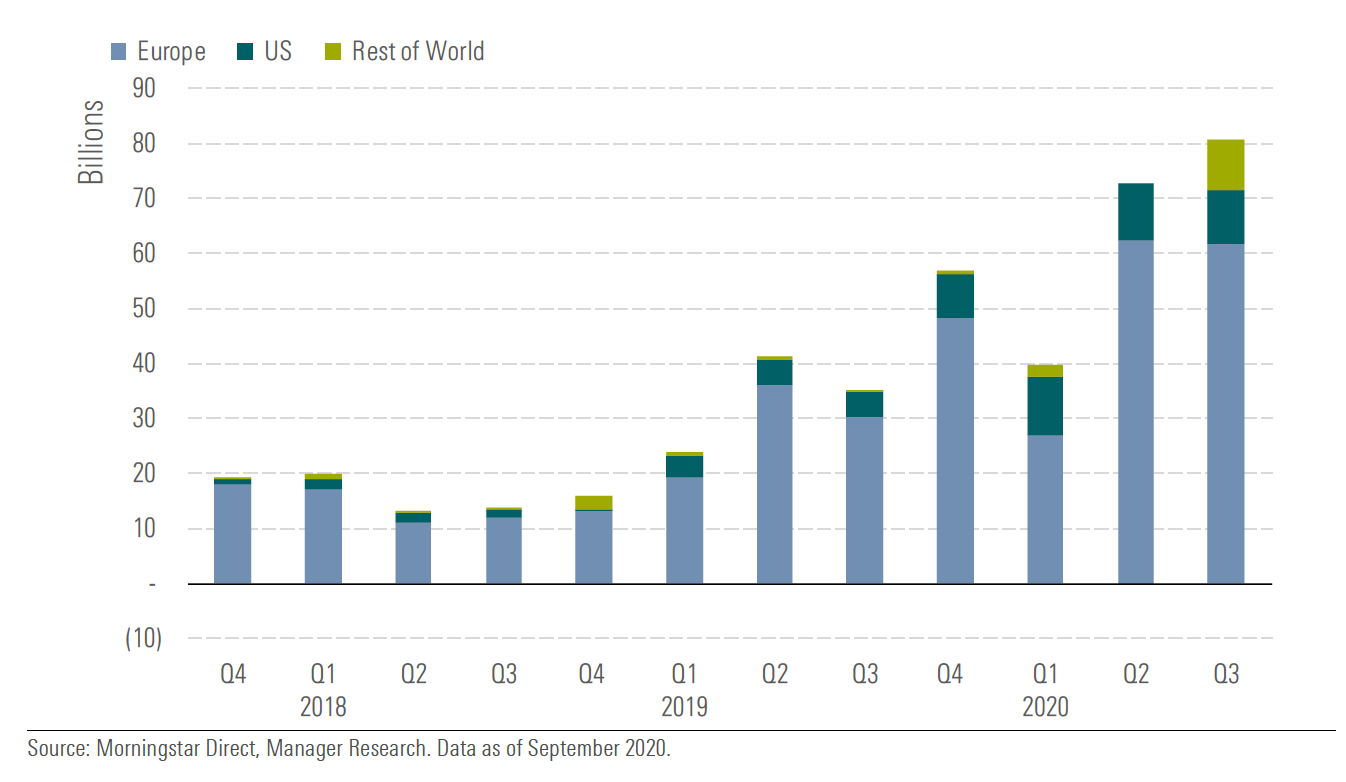

Today, we are very far away from a steady state, simply because the area of ESG investing is growing so much faster than conventional funds. Morningstar has recently published its global and European ESG fund flow analysis for Q3 2020. The chart below shows the inflows into ESG funds globally over the last three years. Flows into ESG funds in 2019 were about four times as large as in any year before that. And in the first three quarters of 2020, flows into ESG funds have already broken the record for the entire year 2019.

Global flows into ESG funds

Source: Morningstar.

Meanwhile, conventional funds see their assets climb at a very low pace if at all. I couldn’t find global data, so I had to make do with the cumulative flows in Europe. Notice the big difference between ESG funds and conventional funds.

European fund flows

Source: Morningstar

This is not a steady-state at all. Instead, we face a steady imbalance between buyers and sellers of green stocks. As ESG funds gather more and more assets they have to constantly bid up the price of green stocks. And as long as this imbalance remains in place, green stocks will continue to outperform brown stocks and there is simply no risk premium for brown stocks that can materialise in the market.

Don’t get me wrong, though. While I think green stocks will continue to outperform brown stocks, I am also convinced that green stocks will eventually end in a bubble and a crash. Just like bank stocks in the 2000s, tech stocks in the 1990s, energy and mining stocks in the 1970s, the Nifty 50 in the 1960s, etc. green stocks will eventually suffer from excessive investor optimism and end in a bubble and crash.

The question is not if we are going to end in a green bubble, but when. And when it comes to the “when” I am pretty relaxed at the moment. Note that ESG investing is not a niche area but encompasses the market as a whole. Just like the rise of index investing, the rise of ESG investing is not constrained to a sector or part of the market. So, a good measure, in my view, of how close we are to a bubble or even a situation where ESG investors dominate the market and thus create a significant shift away from equilibrium that can eventually give rise to mean reversion and thus higher returns for oil and gas stocks, for example, is what share of total stock markets is invested in ESG investments.

Morningstar provides the total assets under the management of ESG funds globally and calculates that to be about $1.2tn. And while that sounds like a lot, it is just about 1% of global equity market valuation. In Europe, the share of ESG funds is highest at around 12.7%. In the UK it is c. 3%. In the United States, it is less than 0.5%. This is nowhere near the levels where one would have to be concerned about ESG investors shifting market valuations.

In essence, while the argument about brown stocks in equilibrium will outperform green stocks may be true, I think the equilibrium is so far in the future that no investor should bet on it today. You will simply have to wait longer than you can stay solvent.

This is a great read. Well, I am biased because I thought similarly. However, there is one piece of ESG that I thought can be profitable (if my ear is on the ground) - shorting companies like Uber at the time the scandal was percolating and then re-enter as a value play later. In the same vein, I should have shorted ATVI (Activision) last week! :-)