Unsexy risks

Today, the annual gathering of the World Economic Forum in Davos ends, and the global leaders of politics, business, and entertainment gathered there can finally stop their virtue signaling and go home to their daily activities where they don’t give a damn about the problems of the world. As if Davos Man wasn’t discredited enough already, this year they even had to deal with the actions of one of their own, Carlos Ghosn, who has shown to the world that you can attend Davos every year and talk a big game about equality and justice, yet, when it comes to facing justice yourself, you rather use your influence and money to escape to a non-extradition country. Peter Tasker has written a great piece about the likely boost these actions will give to left-wing politicians. As I tend to say about Carlos Ghosn:

The entitlement is strong with this one.

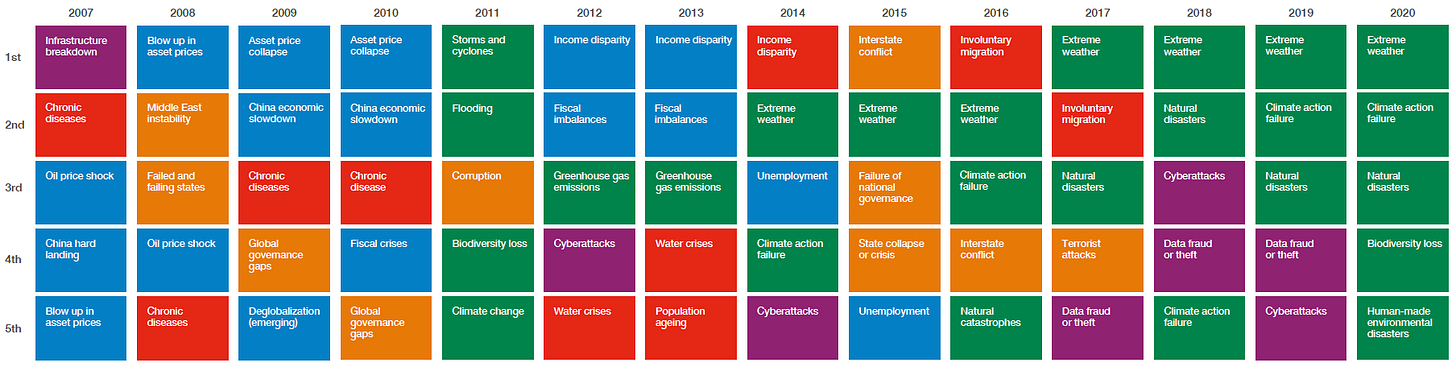

But the WEF also publishes its annual Global Risk Report around the time of the event. In it, the participants of the WEF and experts are asked which global catastrophic risks they find most likely to happen. And every year all they can come up with are the risks that materialised in the previous one to three years. Here is the list of risks the leaders of the world thought most likely to materialise from 2007 to 2020:

In 2009 and 2010 these leaders of the world were most concerned about another financial crisis – mind you that was after the world collapsed and right at the beginning of the longest bull market in history. Inequality only became a topic of concern after the Occupy movement blocked access to office towers on Wall Street and the City of London. And climate change and extreme weather events were only cited once they became so prevalent that they were impossible to overlook.

As a tool for investors or decision-makers in politics and business to forecast future risks, the Global Risk Report isn’t worth the paper it is printed on. But as a reflection of the biases and blind spots of decision-makers, it is indispensable reading. The Global Risk Report is probably the best summary of what Karin Kuhlemann calls sexy risks.

Sexy risks, as Kuhlemann defines them, are neat, quick, and techy.

They are neat in the sense that they are easy to circumscribe and have clearly defined boundaries. The experts who can think about these risks and propose solutions to them are usually specialists in one particular field. Astronomers can help us assess the risk of a meteorite hitting Earth that will wipe out humanity similar to the meteorite that led to the extinction of dinosaurs 65 million years ago. In finance, a stock bubble in a specific market of industry like the technology bubble at the end of the 1990s is another example of such a neat risk.

Sexy risks are also sudden to materialise. They don’t creep up on us, but instead, they materialise after a tipping point is reached or a flip is switched, so to say. A classic example is the likelihood of a global thermonuclear war. If Russia and the United States start throwing nuclear missiles at each other, we can be pretty sure civilisation is going to look quite different in a few months’ time than it did in the past. Similarly, if a stock market bubble bursts, your portfolio is likely to look rather different in a few months than it did in the past.

Finally, sexy risks involve technology. Either technology is the source of a global existential risk (e.g. the rise of deadly AI in the form of Skynet in the Terminator movies), or technology is the solution to any existential risk we may face (e.g. a vaccine to fight off the zombie apocalypse in World War Z, to stay with the movie analogy). In finance, this typically means that bubbles can be found in stocks of companies that promote a new technology like the internet or social media. The risk management tools to reduce risks are often also highly technical and use some form of financial engineering.

In short, a sexy risk is like Catherine Tramell in Basic Instinct. You know it is dangerous, but somehow you think if you are careful enough you can engage and have fun while getting away with it.

Meanwhile, unsexy risks are messy, creeping and politicised.

They are messy, because they have no clearly defined boundaries and to understand them, a number of experts from different fields of expertise have to work together. Take the deforestation of the Amazon rainforest as an example. To understand the consequences of this risk, one needs to understand not only the life cycle of trees but also how the rainforest impacts local and global weather and climate. Furthermore, one needs to understand how poverty drives small landowners and independent miners to invade the forest to make a living farming the soil and searching for gold. One also needs to understand how large landowners need grazing land for their massive cattle herds and push indigenous tribes and local villagers to sell them their land or help them burn down forests.

In finance, such a messy problem is given for example by globalisation. Trade experts may have an understanding how lower tariffs create higher profits for corporations and an incentive to invest in poor countries and create jobs overseas, but it requires insights from psychology and business management to understand how the excess profits from lower tariffs and global value chains will be used in practice. Is the cash going to be handed out to investors in the form of dividends and stock buybacks, or used to invest in capital intensive projects? Or is the money used to increase compensation for existing employees? And how do these measures filter through the rest of the economy? What happens to workers in high-income countries that lose their jobs due to globalisation? How will these workers react to these developments and what kind of social and political pressures will emerge from globalisation? As we have learned in the last decade, no mainstream economist put much emphasis on rising inequality due to globalisation. And the result was a rise in populist policies and policy pressure to reduce inequality.

Unsexy risks have the additional disadvantage that they creep up on us slowly until it is too late. Climate change is a classic example of a risk that increases slowly. For decades, the consensus amongst scientists has been that climate change is real, man-made and needs to be limited in order to prevent catastrophic changes to our weather system and extreme damages to society. Yet, the risk was ignored for many years because it didn’t seem urgent enough. Today, we are in a situation where limiting global warming to 1.5˚C above pre-industrial levels is impossible because it would require reducing carbon emissions to zero by 2030 or at the latest by 2040. Even limiting global warming to the Paris goals of 2˚C seems increasingly unlikely given the non-existent progress we have made on a global scale to reduce greenhouse gas emissions since 2015.

In finance, a similar problem is the funding of our pension system and the social safety net in developed countries. The unfunded liabilities for social security and pension plans alone typically surpass 200% of GDP in Europe. In short, most developed countries cannot afford the social welfare systems they have at the moment, but instead of doing something about it, we continue to kick the can down the road and let our children and grandchildren figure out how to deal with the mess.

Which brings us to the third element of unsexy risks: they are politicised. At the heart of the current climate crisis as well as many other social and environmental crises is one factor and one factor alone: overpopulation. The world’s population has grown too fast. And even though population growth is slowing down since the 1960s, the slowdown is too slow to prevent any of the major catastrophes driven by the need to feed and house too many people on our planet. We might be able to find solutions to our population catastrophe through technology, as Larry Siegel argues in his book Fewer, Richer, Greener. But there is a simple solution that we tend to ignore because it is politically incorrect to discuss: Reduce population growth and global population through policy action. Policies that would penalise having children or limit population growth on a macroeconomic scale are such a taboo that to propose them would make you a Hollywood supervillain. After all the baddie in Avengers: Infinity War is Thanos who tries to eradicate half of the human population.

In finance, all our long-term challenges are highly politicised. From retirement financing to taxes to globalisation. Everything becomes a political football as soon as someone is willing to tackle the problem. And the problem is always the same: We like to protect the benefits we and our family and friends receive while we ignore the costs to people that we do not know (e.g. people living far away in another country or people who aren’t even born yet). It is this present bias and self-centred behaviour that makes solutions to unsexy economic and financial problems impossible.

In short, unsexy risks are like Annie Wilkes in Misery. Not a looker but much more deadly than Catherine Tramell in Basic Instinct and even though you try getting away from her, she chases you down and tries to get you again and again and again.

It is definitely no fun to tackle the unsexy risks in this world, but if we don’t do it, they will eventually transform into sexy risks. Unfortunately, when they do, it is often too late to do anything about them and the end result is catastrophic. Just think of populism in the 1930s or inequality in 18th century France and early 20th century Russia.

And since you have the weekend ahead of you, I challenge you to think about some of the unsexy risks I have mentioned in this post and consider how you and your family can help reduce these risks. Let me know your answers. I am curious.