I am going to do something very dangerous today. I am going to touch on one of the most controversial topics in current politics. I am going to write about immigration. To be clear, this post is not intended to upset anyone. I know there are many dimensions to this debate, most of which have nothing to do with economics, such as the impact of immigration on social cohesion and cultural identity. I am not going to say anything about that except that I agree these are valid concerns. All I am going to focus on today is the economic impact of immigration, knowing full well that this is only one part of the story.

When it comes to the economic dimension, there is the notion that immigrants tend to compete with domestic labour (particularly unskilled labour) for jobs. Thus, higher immigration should lead to higher unemployment and lower economic growth as more government resources are needed to support immigrants through the established social safety nets.

A team from the IMF has shed new light on these claims by looking at large waves of immigrants and refugees to developed countries. The interesting feature of their research is that they differentiate between regular immigration and refugee streams, and they focus only on instances of ‘large’ immigration waves where the annual inflow of migrants is larger than the median annual inflow of both the host country and the average inflow experienced by all OECD countries in the five years before to five years after the ‘shock’. On average, this analysis then looks at migrant flows where the annual inflow of migrants was larger than 1% of the population of the host country (or about 600k per year for the UK, 800k for Germany, and 3.5m for the US).

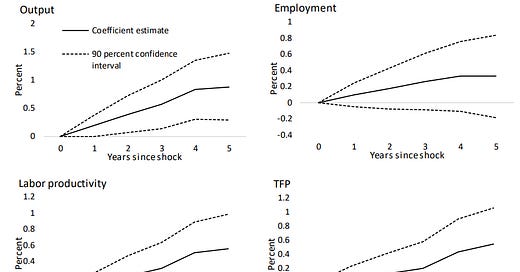

Going back to 1980, here is what happens on average in the five years after an immigration shock for regular migration (i.e. excluding refugee inflows).

Impact of immigration flow of 1% of total employment on host country economy

Source: Engler et al. (2023)

Crucially, these large immigration waves seem to have almost uniformly positive economic consequences. Immigration of 1% of total employment leads to a c. 1% increase in GDP five years after the shock. About two-thirds of this additional output is due to increasing labour productivity and one third is due to an increase in job creation and employment. This explains why countries with relatively strong migration flows over long periods like Australia, New Zealand, or Switzerland all tend to have more robust growth and experience fewer and shorter recessions.

However, much of the immigration shown above is geared toward skilled immigrants. What about the refugee waves that have dominated the political debate? Below is the same analysis for the five years after large refugee shocks.

Impact of refugee flow of 1% of total employment on host country economy

Source: Engler et al. (2023)

Here, the results are more mixed. The economic benefits to GDP are smaller than for regular immigration flows though marginally positive as well. After five years, a refugee flow of 1% of employment leads to a c. 0.5% increase in GDP. This increase in GDP is entirely driven by increasing employment and, crucially, the authors of the study find no evidence for refugees competing with or even crowding out native workers. As so many studies have found previously, immigrants are not competing with native workers but form a different class of job seekers. Yet, there is evidence in the data that where there is strong social support for refugees and refugees are integrated into society (and most importantly the job market) faster, the economic impact is larger.

Overall, the research points to a relatively benign economic impact of immigration. Skilled immigration is undoubtedly positive for the economy, employment, and productivity. Refugee waves are more ambivalent, but countries can make refugee shocks more of a success by developing policies that enable refugees to integrate into the local job market faster (e.g. through intensive language courses and the recognition of foreign professional certifications and degrees).

.....and sometimes these waves of industrious immigrants include people who publish economic data, articles etc. and thus increase the human capital of the population as a whole.

Sensible to restrict scope to effects on economy and within that only the effect on GDP.

This article addresses absolute increase in GDP - increase from £100 to £102. What about GDP per capita of population - at the same time this could fall from £1 to £0-98. Is GDP per capita a better measure of benefit to citizens?

Outside scope, but still an ‘economic’ effect, is competition demand for resources adversely affecting citizens e.g. average house price rises from £1000 to £1250.