In the United States and Western Europe, inflation is at multi-decade highs and central bankers are rightfully afraid that high inflation might lead to high wage inflation and stat a wage-price inflation spiral similar to the 1970s. But the link between inflation and wages today is much weaker than it was fifty years ago and examining the reasons why gives us an understanding of what needs to happen to start a new spiral.

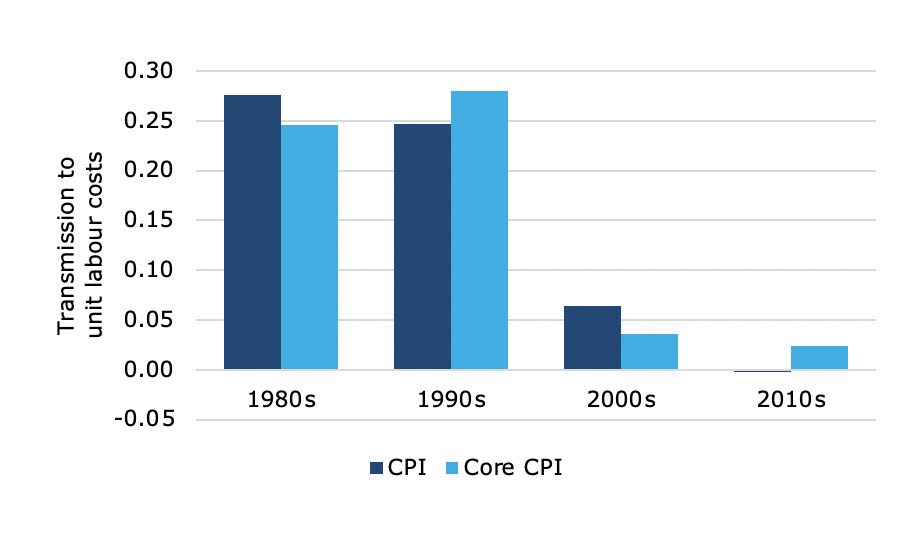

That the link between inflation and wages has weakened enormously can be seen with the data collected by economists from the Bank for International Settlement. The chart below shows the impact an increase of one percentage point in CPI or core CPI has on unit labour costs across 21 developed economies ranging from the US to the UK, all Eurozone countries to Australia. For example, in the 1980s a one percentage point increase in headline inflation led on average to an 0.28% increase in unit labour costs. It’s important to use unit labour costs here because if wages rise, businesses react to higher wages with investment in productivity-enhancing measures like better machinery which reduces the demand for labour and thus reduces unit labour costs. Because of these mechanisation efforts, the impact of higher inflation is less than the pure impact on higher wages. But while it was 0.28 in the 1980s, we see that it has almost completely vanished by the 2010s.

Impact of 1% higher inflation on unit labour costs

Source: Kohlscheen and Moessner (2021)

But why did the link between inflation and unit labour costs drop so much in the early 2000s? The answer seems to be the rise of globalisation and in particular the membership of China in the WTO in 2001.

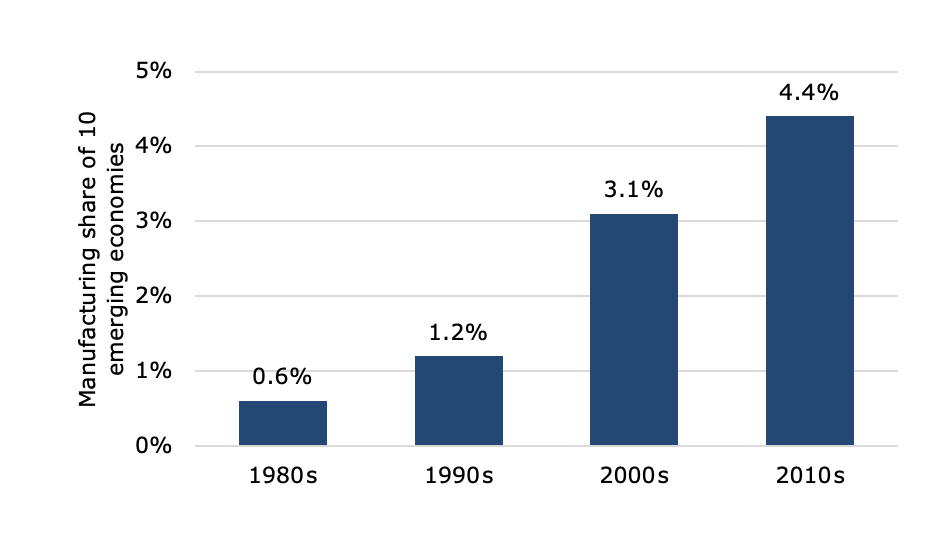

A study in 2013 already found that for every percentage point of the manufacturing market captured by six large emerging markets (China, India, Mexico, Philippines, Thailand, and Malaysia), producer prices dropped by 3%. Below is some data for 10 emerging markets (adding Czechia, Hungary, Poland and Turkey) and their share in developed markets manufacturing.

Manufacturing share of emerging markets

Source: Kohlscheen and Moessner (2021)

Knowing this brings us both good and bad news. The good news is that it is unlikely we are going to see a wage-price spiral unfold in the next couple of years that is similar to the 1970s or the 1980s. As long as global supply chains remain intact, wage competition from developing economies is so strong that wages in industrialised countries cannot rise significantly faster than inflation. In fact, real wage growth will likely remain close to zero or even negative.

The bad news is that the link between globalisation and producer prices is extremely sensitive (remember the 3 to 1 sensitivity mentioned above?). Even a little bit of de-globalisation can increase the link between inflation and wages significantly. And with our recent experiences from the pandemic and supply chain disruptions there more businesses starting to think about how they can become less dependent on countries like China, Taiwan, or now Russia. This means reshoring production facilities closer to home, whether that is Mexico for US businesses or Turkey and Central Europe for European businesses. And in some instances, this may mean re-shoring production facilities to a developed country.

All of this will take time. One cannot redirect global supply chains in a year or two. Rather it will take three to five years or even longer. And re-shoring to high wage industrialised countries will likely come with heavy investments in robots and other labour-saving technologies in order to avoid having to pay high wages. But while we are probably safe from starting a wage-price spiral in 2022, we will become increasingly vulnerable to such a spiral as the decade progresses. And investors need to monitor these developments closely in order not to be caught off guard.

Thanks for your article!

When I'm looking at producer prices, I'm seeing double-digit numbers for most developed countries by just glancing at tradingeconomics.com. I agree that it could even be a lot worse if China saw some inflation, but it's impossible for productivity growth to catch up with that rise in PPIs anytime soon.

https://tradingeconomics.com/country-list/producer-prices-change?continent=europe