What gets measured gets done, ESG edition

We all know that how you measure things determines what will be done and how it will be done. Interestingly, this also has implications for ESG investing and the ESG activities of corporations.

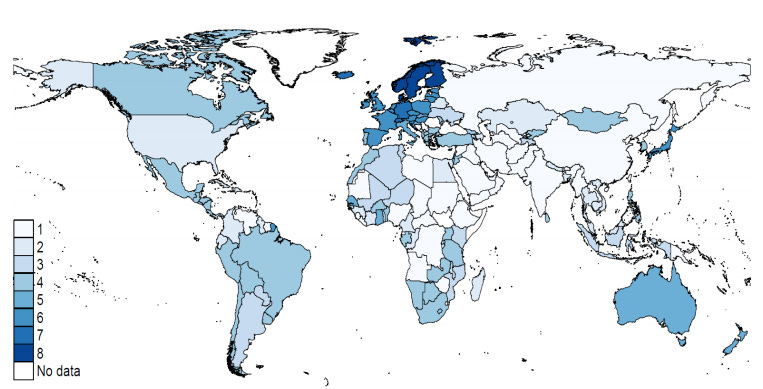

The chart below shows the average ESG scores of companies in different countries. Scandinavia is clearly ahead of the rest of the world, followed by continental Europe, then the UK, followed by North America. The worst ratings are in the former socialist countries like Russia and Eastern Europe.

Average ESG rating of companies by country

Source: Liang and Renneboog (2017).

As someone who is a trustee of a North American not-for-profit and deals with investors from all over the globe, I always find it interesting how different the opinions on ESG are between Europe, the US and Asia, let alone emerging markets. I am willing to give emerging markets a break because they have to catch up with the developed world and ESG issues are not top of the agenda in many cases. But why do American companies and investors care less about ESG than Europeans? Come to think of it, why do British companies and investors lag French, German or Scandinavian companies and investors?

Hao Liang and Luc Renneboog claim that a major explanation to this puzzle (much more than fundamental differences in the nature of the business of companies, etc.) is the structure of the legal system. In continental Europe and Scandinavia there is a civil law system which, in the context of corporate law, emphasises the diverging interests of different stakeholders. There simply is a far longer history of stakeholder management in Europe as reflected by employee representation on the board of directors in Germany and a mandate for boards to act in the best interest of all stakeholders.

Meanwhile, in the Anglo-Saxon world the common law tradition emphasises the primacy of shareholder interests as owners of a corporation. These countries are relative newcomers and less experienced in balancing diverging interests of different stakeholders. In fact, a common objection in these countries is that stakeholder value maximisation is not possible because of contradictory objective. This concern has by now been shown to be unfounded since shareholder value maximisation leads to pretty much the same contradictions in objectives. Together with my friend Michael Falk, I have recently written a paper on stakeholder capitalism that I will talk about here, once it has been published.

In the meantime, let us just show that as the legal setup changes, different things get measured. And as a result, corporations act more or less sustainably and have better or worse ESG ratings. What gets measured gets done…

Average ESG rating by legal tradition

Source: Liang and Renneboog (2017). Note: Score ranges from 0 = lowest to 6 = highest.