Finance, Bubbles, Negative Rates: The What Ifs . . . ?

This article was originally published on the Enterprising Investor blog on 24 February 2020.

I rewatched the Orson Welles docudrama F for Fake the other day. The 1973 film is an exploration of what is fake and what is real in the art world. I was curious to see how it held up in the age of fake news.

Well, the movie doesn’t have too much to say about fake news, but it does reveal quite a lot about financial markets, financial bubbles, and our current interest rate environment. One of the key concepts the film examines is how a forgery can be passed off as authentic in the ecosystem of the art industry.

In that world, there are real artists who create paintings, sculptures, and literary works that truly stand out and provide deep insights into humanity. Then there are the art forgers who imitate these true pieces of art for financial gain. What these forgers need is an expert to certify that the forgery is indeed authentic and then an art dealer to sell the fake as real to unsuspecting investors and collectors.

See where this is going?

Today’s financial industry has true entrepreneurs who create products and services that improve our lives and bring real progress to our society. Then there are fake entrepreneurs (or managers) who imitate true entrepreneurs to increase the market value of the companies they work for — and their personal financial wealth through higher share prices — without actually creating anything new.

In the business world, they tend to accomplish this by cost-cutting and M&A activity. What these fake entrepreneurs need are experts (or analysts) to certify that their actions constitute authentic added value for the company. And they need stockbrokers to sell fake progress as the real thing to unsuspecting investors.

If the stockbrokers are successful enough in pushing up the share price or of the market as a whole, it will become so obviously detached from reality that some analysts will call it a bubble. Which is another important concept F for Fake explores. When is a fake a fake?

When Is a Bubble a Bubble?

In the art world, a fake is a fake when the consensus opinion of experts declares it as such. As Oja Kodar asks in the movie: “If there weren’t any experts, would there be any fakes?” Without experts, all art would be real.

A friend told me he is trying to find a way to classify bubbles before they burst. Which raises the question: When is a bubble a bubble? Is a bubble that never pops still a bubble? Can we only identify bubbles after they burst? Or is their objective criteria that defines a bubble independent of the pop? Plenty of effort has been spent identifying bubbles in real time, so far with very limited success.

So what if there are no bubbles in financial markets? What if bubbles can only be identified based on their bursting. No bursting, no bubble.

Or to put it in the words of art forger Elmyr de Hory in the movie:

“If you hang them in a museum in a collection of great paintings, and if they hang long enough there, they become real.”

What if Negative Is the New Reality?

In today’s financial markets, we live in constant fear of the low interest rate bubble bursting. Wary of extremely low or even negative interest rates, many analysts and economists expect a massive devaluation of assets once interest rates normalize.

But more than 10 years after the financial crisis, interest rates have yet to normalize in the United States or Europe. And in Japan, 30 years after the bubble burst, interest rates haven’t normalized either.

How long do low or negative interest rates have to hang before they become real? What if this isn’t a bubble or historic aberration but a permanent state of reality?

According to the currently accepted wisdom on financial markets:

Real interest rates and nominal interest rates cannot stay this low forever.

Real interest rates remain stable in the long run and fluctuate around a level of 1%.

The difference between the real rate of interest and the real rate of growth is constant over time fuelling rising inequality between owners of capital and workers.

The equity risk premium is constant in the long run.

What if all these assumptions are wrong?

In an absolutely fascinating must-read, Paul Schmelzig challenges each of these doctrines. He compiles data on global real interest rates and the difference between real economic growth and real interest rates spanning more than 700 years. His extended timeframe and reliance on primary rather than secondary source data paints a very different picture of the above assumptions.

If his data is correct — and the results are so revolutionary, we ought to be cautious about assuming as much — then real interest rates are in a long-term decline, with a slope of about 1 to 2 basis points (bps) per year. This means that today’s low real interest rates aren’t an anomaly. Rather they represent a return to a long-term secular trend that was interrupted by rising real interest rates from 1950 to 1990.

Again, if Schmelzig is correct, “normal” real interest rates are not coming back. Instead, they will eventually turn negative on a global scale. And they will stay there for a long time — with only occasional cyclical upward swings.

Long-term declining trend in real interest rates

Source: Schmelzig (2019).

The share of global GDP with negative long-term real rates correspondingly shows a rising trend. All the last decade has done is bring the share of global GDP with negative real rates back to historical norms. If the research is accurate, the United States will eventually join the club of countries with negative long-term real rates.

Share of developed market GDP with negative long-term real rates

Source: Schmelzig (2019).

But that isn’t the end of Schmelzig’s revelations.

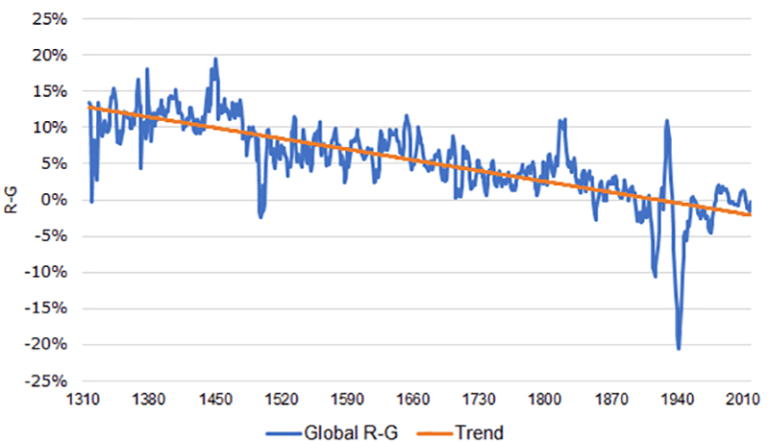

In what may be even more consequential for investors, he demonstrates that the difference between real interest rates and real economic growth (R-G) is not constant at all, but also steadily declines. The current level of R-G is effectively a little high, which suggests that it will continue to fall in the years ahead.

This is of immense importance because it implies several important trends:

Sustaining high volumes of sovereign debt without defaulting grows easier over time. So Japan’s debt-to-GDP ratio might not be an outlier but a harbinger of what is to come in Europe and the United States.

Inequality between labor and owners of capital, which is driven by R-G, might not increase forever but eventually level out and decline. It can only grow indefinitely if savings rates rise at least as fast as R-G falls — something we have yet to observe.

Risk premia for risky assets like equities are largely determined by R-G as well. If R-G remains low for the foreseeable future, these risk premia should remain low too — barring the usual spikes in risk premia during recessions, etc. This means that equity returns and excess returns over bonds and bills will remain low and continue to decline in the coming decades.

Declining risk premia imply a sustained increase in valuations so such long-term valuation metrics as the cyclically adjusted PE (CAPE) ratio may never fully revert to their historical means.

To be sure, these are all big What ifs? But if Schmelzig’s analysis is right, we might have to fundamentally reconsider what is real and what is fake in financial markets.

Long-term difference between real interest rates (R) and real economic growth (G)

Source: Schmelzig (2019).