ETFs are great investments. They are low-cost and easy to understand. Yet, they are not without their drawbacks. One well-known drawback is that hedge funds replicate indices and this means that if the index changes and drops a company from its membership while admitting another, ETFs become forced sellers of the dropped stocks and forced buyers of the newly included stocks. This gives hedge funds an opportunity to front-run the ETF trades.

This is why the announcement effect isn’t really visible anymore in stock markets. In the past, the share price of a stock newly included in a major index like the S&P 500 would jump on the day this inclusion was announced. But with indices having relatively strict rules (not so the S&P 500 which has a panel that has discretion about index inclusion) hedge funds can anticipate the likely inclusions and buy them weeks in advance. This hedge fund arbitrage tends to increase the price of stocks that are included in the index and lower the price of stocks that are excluded.

A study from Lancaster University looked at ETFs tracking US indices and examined hedge fund investment positions around the time of index reviews. They found that ETF investors who replicate indices on average buy stocks newly included in an index at a 0.86% higher price than is justified when compared to share prices of stocks with similar characteristics that are not introduced in the index (either because they are already included in the index or because they are too small to be part of the index). And of course, once these newly added stocks have become part of the index, hedge funds close their positions and share prices of these stocks drop more than normal creating underperformance in indices and the ETFs tracking these indices.

But don’t worry. Because index changes are typically small, the performance impact on ETFs is generally small. However, some readers may think if a hedge fund can do that, so can they. Why don’t other funds and investors not join in the frontrunning game thus pushing this effect further out and possibly making it even larger?

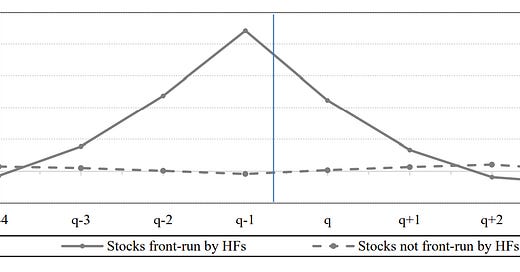

If you look at the chart below you will find the reason. It shows the timing of hedge funds putting on these arbitrage trades of buying newly included stocks and selling excluded stocks. Because hedge fund data about their portfolios are only available on a quarterly basis, the researchers had to look at the different quarters before an index review and could not be more granular. But even so, the results are surprising to me. Hedge funds put their arbitrage trades on about a quarter before the index actually changes creating the peak in share price appreciation (blue line in the chart below) a couple of months before the index review is implemented.

That is a very long time. Hedge funds start betting on new stocks in an index shortly after the last review has been implemented and then create the index inclusion effect so early, that share prices peak one or two months before the actual inclusion in the index. I don’t think any normal investor can predict index inclusions that far in advance, which is why in practice it might simply be impossible to front-run or even join in with sophisticated hedge funds in index arbitrage.

Hedge fund arbitrage trades before index revisions

Source: Wang et al. (2023). Note: Quarter q is the quarter of index review, the vertical blue line indicates the time of maximum share price impact.

Could it simply be that hedge funds have alpha, so the stocks they buy tend to rise in price and that makes them more likely to meet index criteria? It’s not necessarily an explicit index arbitrage trade.

Curious why only ETFs? Wouldn't this impact mutual funds as well or is this like the financial media moving away from the DJIA? :)