Index funds and ETFs are gaining market share in most countries. And yet, if they buy shares in a company, who sells their shares? As index trackers become more prominent in the marketplace, who is divesting? That is the question Marco Sammon and John Shim asked and their answer may surprise you.

My intuitive answer to the question of who sells to index trackers would have been active fund managers. After all, many active fund managers have seen systematic outflows for years. However, using quarterly holding data of US equity funds and US companies, they find that actively managed equity funds tend to buy when index trackers buy as well. Yes, in the long run, actively managed funds have to sell stocks to cover redemptions, but they do not tend to sell the stocks index trackers buy, or at least not at the time when index trackers buy them.

The same is true, though to a lesser extent, for hedge funds, insurance companies, and pension funds. Other financial institutions like banks tend to sell a little bit to index trackers, but it hardly makes a difference.

Wait a minute. All the big investor groups from active fund managers to pension funds, insurances, and banks tend to either buy at the same time as index funds or not change their positions at all. Then who is providing the liquidity?

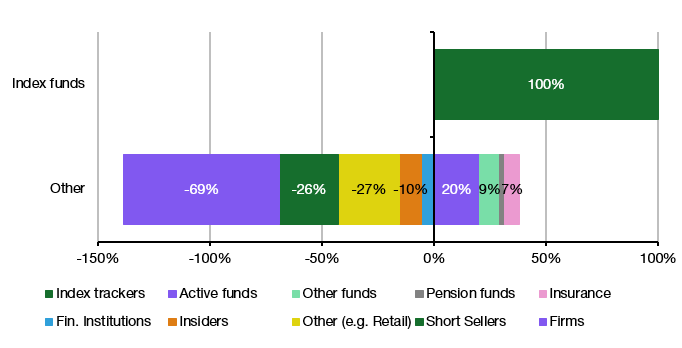

The chart below gives the answer, and it did surprise me, I have to say. The largest sellers of stocks to index trackers are the companies themselves. For every share bought by index trackers in a specific company, the company itself issues about 0.7 new shares to the market. Another big chunk of the total supply comes from short sellers and other investors like retail investors. Plus, corporate insiders tend to sell shares in their company to the market when index trackers buy.

Supply of shares bought by index trackers

Source: Sammon and Shim (2024)

Again, wait a minute. Aren’t companies buying back shares all the time rather than issuing new ones? Yes and no.

Be aware that the statistics above are an aggregate over the entire market. While some companies are buying back shares, others are issuing new shares through primary offerings. And while the media is full of reports of company X announcing a new buyback programme, news reports of company Y issuing new equity capital are exceedingly rare (and typically only happen when a distressed company raises new capital to survive).

But the chart below shows that in any given year, companies issue many more shares (by number and value) than buying them back. And because with a higher number of shares in circulation, the weight of a company in an index increases as well (note to self: it’s not just share price performance that matters for index weighting). Index trackers are then forced to buy more shares of the companies that issue this new capital.

Aggregate share issuance and buybacks in the US

Source: Sammon and Shim (2024)

All this shows two important things, in my mind:

First, always check the number of outstanding shares of a company. Reducing the number of shares through buybacks boosts earnings per share because the same profit is divvied up between fewer shares. However, increasing numbers of shares in circulation happen more often and dilutes earnings per share.

Second, when we talk about earnings growth and valuation measures like price/earnings-ratios, we tend to implicitly assume that the number of shares remains constant while demand for these shares from investors changes. This is not true. A rising P/E-ratio indicates demand outstripping supply while a declining P/E-ratio indicates supply outstripping demand. Demand for shares in a company can rise and yet the price can drop if the company issues more shares than the market can handle. It’s a subtle difference but one that sometimes can be very important.

Wow, surprising indeed. This is one of these topics about which when noobs ask me, all I can do is shrug. Not no more, tho!

One wonders what this implies. Can I assume that all this easy issuance with a reliable buyer effectively lowers to cost of capital? If so, then this could be a positive feedback loop explaining some of the U.S.'s stock market strength (until the point where it turns into a circulus vitiosus).

Confess to a slight uneasy feeling here. Index fund gives £1m to large corporation (market cap say £10bn). Corporation creates £1m worth of new shares (0.01% of market cap) and gives them to index fund.

Existing shareholders might just have had their pockets picked... depending whether the company spends the £1m on something useful or on giving the top management team two weeks all expenses paid skiing holiday in a five star hotel in a fancy resort...