It is Fed Day (again) and the central bankers have to decide how on Earth to deal with a US economy that not only has gone on a glide path to a soft landing but for the longest time looked like it would not slow down at all. Of course the US could still slip into recession and later this week the Sahm Indicator as a recession signal in the US could be triggered. But for now, it very much looks like the US will be able to avoid a recession or at least land much softer than Europe.

The impact of the rate hikes could hardly be more different across the Atlantic where both the Eurozone and the UK slipped into recession in late 2023 and are now slowly climbing out of a hole. How is it possible that central banks on both sides of the pond did essentially the same thing but the economy reacted in very different ways?

A paper by the San Francisco Fed provides some answers. Adam Shapiro, one of the authors of the paper, has developed some time ago two data series that show the inflation from supply-driven factors like the sudden loss of natural gas after the Russian invasion of Ukraine and demand-driven factors like a buoyant job market and strong consumer demand.

He shows that in 2022 the US first experienced a supply-driven inflation shock that quickly abated while a demand-driven inflation shock driven by household and government spending after the pandemic emerged.

Many people expected some form of financial crisis to emerge as the Fed ended 15 years of zero interest rate policy, but besides a short-lived shake-up of US regional banks in the wake of the Silicon Valley Bank failure nothing happened. Barely a month later we were back to business as usual.

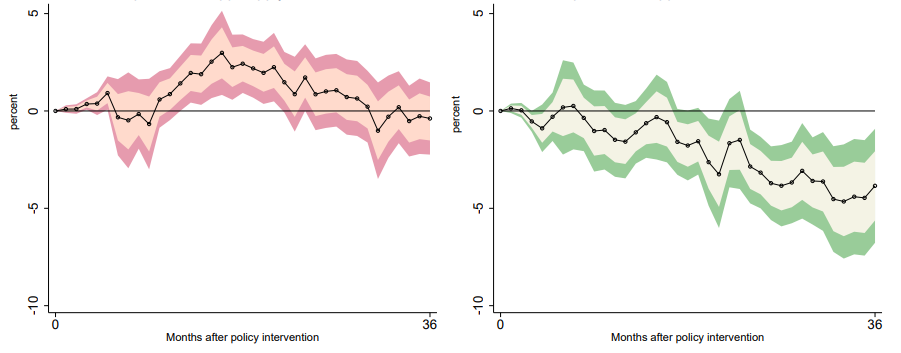

The charts below show that financial stress does indeed increase after the Fed fights a one percentage point inflation shock. But it only increases if the inflation shock is driven by supply factors. When the inflation shock is driven by excess demand as it was in 2023, financial stress tends to decline in the aftermath of rate hikes.

Financial stress in the aftermath of inflation shocks

Source: Boissay et al. (2024)

What seems to happen is that supply shocks hit businesses and households when their finances are already not ‘optimal’. Some businesses may be struggling anyway to make a profit and any cost increase rapidly forces a business into bankruptcy. But when the economy is running hot, such business defaults are rare and businesses have more of a margin to digest higher interest rates from the Fed.

The same pattern can be seen when one looks at the unemployment rate after an inflation shock. Supply-driven inflation shocks lead to an increase in unemployment as businesses go bust and people are being laid off. Demand-driven inflation shocks don’t because businesses try to keep as many people on payroll as possible to cope with high demand.

Unemployment rates in the aftermath of inflation shocks

Source: Boissay et al. (2024)

Which brings me back to the original question of why the US economy was so much more resilient than Europe in the wake of large rate hikes by central banks.

If you think back to 2021, the US economy bounced back much faster and much more vigorously from the pandemic than most of the Eurozone or the UK. On top of that the US government turned on the spending taps big time through pandemic relief and later the Inflation Reduction Act. When Russia invaded Ukraine and gas prices spiked, the US economy was in a much better state than Germany, France, Italy, or the UK.

These weaker economies were also hit much more directly with the supply disruption from a stop to Russian natural gas exports so that businesses in Europe had a very difficult time digesting the rapidly rising energy costs. The result were more defaults and more layoffs in the UK and Eurozone and an economy that eventually dropped into recession, just like most economists expected. There was hardly any demand-driven inflation in the UK and Eurozone in 2022 or 2023 because households didn’t see many wage increases and suffered under rapidly rising energy bills and mortgage rates.

In the US, the energy crisis was not that extreme and mortgage rates hardly moved since everyone is sitting smugly on a 30-year fixed rate these days. So why worry about higher mortgage rates. Rather spend the money and enjoy yourself, thus adding more demand-driven inflation and forcing the Fed to stay higher for longer in its interest rate policy.

Of course, now the tables are beginning to turn as the Eurozone and the UK come out of recession and central banks can cut interest rates while the Fed has to keep rates high and slow down the US economy. 2025 is shaping up to be an exciting year in terms of monetary policy and financial markets…

It always baffles me why the UK and European banks don't simply issue 30-year fixed-rate mortgages. UK floating rate resets appear to be particularly disruptive events.

The energy thing is huge; we manage our household finances very tightly (especially now that I'm retired), but sharply higher gas and electricity prices in Germany have us economizing and forgoing discretionary expenses to an extent I never contemplated. Meanwhile, back in the States, it's business as usual for my retired parents, who just bought a new car.