We all have different talents. For example, I am good at maths and abstract thinking. And that’s not bragging, it is just that I have a postgraduate degree in mathematics and physics which statistically puts me into the top 10% of the population with the highest math skills. But while I am good at maths, I am absolutely rubbish at languages. I speak German and English but have struggled to learn any other language. Similarly, I cannot keep a tune or play an instrument (and I think this is connected to my inability to learn languages).

But what if I tell you that while we may all have different starting points in terms of talent, every one of us can become proficient in any subject? And we do so at the same rate as the most talented people do. I might be bad at languages, but I might still be able to become proficient in Japanese or Arabic (two languages that I really would love to learn). You may be struggling with maths, but you may still learn to do advanced calculus and integrate the living daylights out of functions.

That may sound overly optimistic, but it is what research about learning shows.

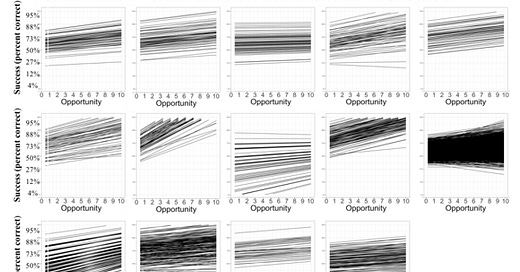

Look at the strange charts below. They show the learning progress of college students in different subjects from maths to languages and for different courses. Two things stand out. First, there tends to be a wide variety of skill or knowledge at the start of the course as indicated by how far apart the individual lines are. As students have opportunities to learn (noted on the horizontal axis of each chart) they tend to get better at answering exam questions. But note that the individual lines don’t just rise at random speeds. All the students, whether they start out as good or bad students tend to learn at the same speed as indicated by the largely parallel lines in the charts.

Speed of learning in academic courses

Source: Koedinger et al. (2023).

The authors of the paper where these charts come from provide the best summary of what that means:

“Our evidence suggests that given favorable learning conditions for deliberate practice and given the learner invests effort in sufficient learning opportunities, indeed, anyone can learn anything they want.”

And this is really the point. What keeps us from learning the things we want to learn is not a lack of talent. It is either a lack of practice or a lack of deliberate practice.

I may not have the time to enrol in a Japanese language course, so I never practice, and my Japanese never gets any better. Or I may enrol in such a course, but my practice sessions are not of high quality, i.e. I don’t practice deliberately. Deliberate practice is what makes us successful at a task. Deliberate practice means breaking down a skill into its constituent parts and then fully focusing on learning the individual parts of each task. Rinse, repeat, but always focus. Never get distracted, never mentally drift off and never slack or take shortcuts.

If that sounds hard, that’s because it is. In my experience most students at school or university sit in a class and only pay partial attention (if at all). Even if you are participating in a course that you want to study, you are often distracted by other things going on around you, whether it is the message popping up on your phone or the sounds from the kitchen, you tend to lose focus and that undermines your efforts and reduces learning.

I would even go as far that we are most likely to engage in deliberate practice consistently over time if we are truly passionate about a subject. And as far as I am concerned, I like maths and thinking about the world in broad abstract terms, but I am not very passionate about memorizing Japanese syllables and words. So, while I practiced my maths skills deliberately for many years, I have never deliberately practiced my Japanese.

But that doesn’t mean I cannot do so in the future. I have the skills necessary to learn Japanese and you have the skills necessary to learn whatever you want to learn. Now it is up to you to decide how to create an environment where you can deliberately practice this skill until you master it. You can do it. We all can.

Self-help, as viewed via the lens of finance and logic.

I wonder if this implies, contra Buffett, that knowledge does not compound but is linear? If knowledge compounds wouldn’t we expect more proficient students to learn at a faster rate?