A former colleague of mine who covered bank stocks likes to say that banks cannot cut their way to profitability. In my view this applies not just to banks but to every high-tech manufacturer and most services companies. In other words, most of our modern economy. You cannot cut costs to become more profitable. You can only invest your way to profitability.

When times get tough, business executives tend to have an instinctive reaction: We need to cut costs to preserve our profitability. While there is nothing wrong with temporarily cutting costs to reduce overhead and bloated company structures, cutting costs also means cutting knowledge, damaging customer relationships and reducing employee productivity (nothing like a wave of redundancies to demotivate the workforce). Hence, the more a business relies on knowledge, expertise or its network of relationships, the higher the costs of short-term cost cutting.

But as I said, in today’s economy, the majority of businesses are knowledge businesses, so reducing employees imposes a significant cost to the organisation. Alternatively, one can cut capital investments, which preserves knowledge but reduces future growth and innovation.

History is full of businesses that have tried to cut their costs to profitability, just to end up cutting themselves into irrelevance. And I have to say that in my experience this is a particularly American disease. American managers are obsessed with costs and don’t care about the decline in quality of the product as costs are being cut:

Think of Boeing after the merger with McDonnell Douglas when the ethos of the company changed from being run by engineers to one being run by accountants.

Or think of US airline companies in general. Here is a list of US airline companies that have filed for bankruptcy: American Airlines in 2011, Continental in 1983, Delta in 2005, Northwest in 2005, PanAm in 1991, TWA in 2001, United in 2002, and US Airways in 2002 and again in 2004. Meanwhile, there has only been one major airline bankruptcy in Europe (outside of no-frills startups) in the form of Swissair in 2002.

And what about US Steel which has tried to cut its costs to compete with cheaper rivals from Asia just to end up on the verge of bankruptcy?

I could mention General Electric, General Motors, and many others, but let’s look at a more systematic picture.

The chart below shows the profitability of companies in the US, UK, and Europe as measured by return on capital. Clearly, the profitability of US businesses has significantly accelerated well above the one seen in the UK and Europe over the last 15 years.

Profitability of companies in the US, UK, and Europe

Source: Liberum, Bloomberg

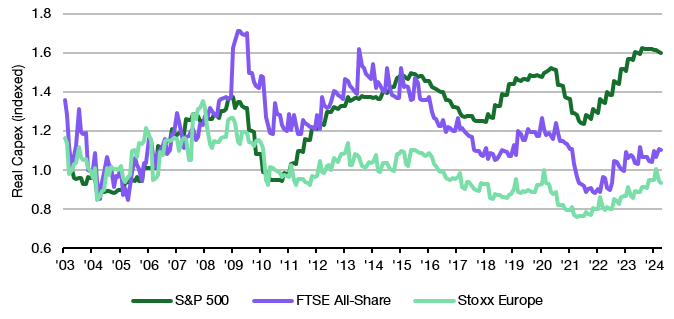

One reason could be the rise of US megacap tech companies which have higher profitability than other businesses, but I would suggest that this higher profitability is not just a result of intrinsically higher margin, but at least partly a result of higher capex. My second chart below shows total capex adjusted for inflation and indexed to the same starting level (January 2003 = 1).

Real capex in the US, UK, and Europe

Source: Liberum, Bloomberg

Until the financial crisis, capex trends in the US, UK and Europe were almost identical, but since then, things have diverged significantly. In Europe the companies in the Stoxx Europe index have systematically reduced their capex (after inflation), while US businesses continued to invest more and more. In the UK, businesses followed the US model until about 2015 and since then capex has declined significantly in real terms.

If we look at the relationship between capex and profitability, the short-term relationship is from profitability to capex. Businesses that see their profitability decline decide to cut investments and reduce capex. But if one looks at longer-term trends, it becomes clear that this cuts both ways. Reduced investments create less productive assets and employees, which in turn reduce future profitability. Below is the rolling 3-year average profitability of the companies in the S&P 500 together with the rolling 3-year growth rate in real capex.

Trend profitability and capex growth in the S&P 500

Source: Liberum, Bloomberg

The correlation is obvious. And in my view, this is not just correlation, but causation. Indeed, I have written before about how businesses that cut the right costs can preserve profitability while cutting the wrong costs (most notably R&D expenses) leads to significant long-term impairment of profitability.

For completeness, let me sow you the same charts for the FTSE All-Share and the Stoxx Europe.

Trend profitability and capex growth in the FTSE All-Share

Source: Liberum, Bloomberg

Trend profitability and capex growth in the Stoxx Europe

Source: Liberum, Bloomberg

What these charts show is not just that you cannot cut your way to profitability, but also, in my view, that you have to invest to increase profitability. Indeed, in the long-term it seems to me that one can only increase profitability by increasing investments. And for long-term investors that implies that one should be very cautious before investing in companies that focus on cutting costs or have a history of reducing their capex in real terms.

The correlation in the chart 'Trend profitability and capex growth in the S&P 500' is obviously there but I am asking myself whether the causality is not the other way round

- If the causality were as suggested, there would be a substantial time lag between capex and profitability (investments need time to pay off). One cannot see that in the chart.

- If the causality were the other way round, no time lag would show (as is the case in the diagram): High profits (for any reason) make management immediately more optimistic and increase capex.

This is not in contradiction to the argument that capex increases profitability in the long run, it just reverses cause and effect in the short term.

Fished this important piece out of the must-read printed off stack. It's spot on to address the question of the relationship between spend and growth. Stops short of macro or managerial NPV analysis (what can anyone do in a 3pp Substack!).