While the forecasts of the decline of the US Dollar come straight out of the land of flying pigs, today’s topic of common doom and gloom forecasts isn’t outright crazy. In fact, it is entirely possible to happen, but as I will argue in this note, I think the consequences of such a development would be so severe that it is highly unlikely it will ever materialise. I am talking about normalisation of short-term interest rates to 5% or more, levels we used to have in the 1970s to 1990s.

To keep things simple, I will talk about the Fed Funds Rate in the United States as the reference rate for short-term interests. I have done the same exercise for the UK and Eurozone and readers who subscribe to Liberum research can send me an email to get the full analysis. Here, I will just show why I think it is impossible at the moment that we will see a permanent return to interest rates of 5% or more in the US.

First, let’s have a look at Fed Funds Rates in the US. Yes, over the last 15 years or so, the interest rate was very low and it only now moved back up to 5% in response to the significant inflation we experienced in 2022. The argument of some doomsayers is that inflation will remain so persistent that the Fed will not only have to keep interest rates at current levels for a very long time but have to hike much more than is currently expected and move rates back to levels well above 5% and even 10%.

Fed Funds Rate since 1954

Source: Bloomberg

But I don’t want to criticise this point of view too harshly because it is entirely possible, in my view, that we may enter a prolonged period of very high interest rates. Let me start by sketching out my view on this. I think that inflation will decline slowly (slower than the market expects at the moment) and that the Fed will eventually cut interest rates.

However, if the Fed cuts interest rates too soon when inflation is still high, it will likely create a spike in demand-driven inflation in 2024 that forces the Fed to hike interest rates once again, but this time starting from levels around 3-4%, not 0%.

This is the mistake the Fed made in the 1970s and what led to the spiral of ever-increasing interest rates and inflation. Fed officials emphasise that they are fully aware of this policy error and do not want to repeat it, but only time will tell if they are able to avoid this fatal mistake.

Having said that, what would happen if the Federal Reserve Rate remained at 5% for the coming years or even goes to 10% or so?

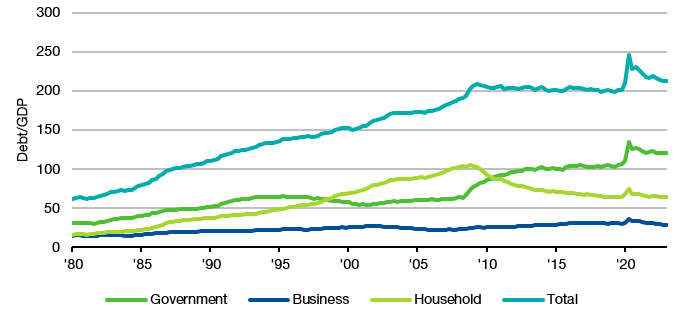

First, we need to recognise a crucial difference between today and the 1970s and 1980s. The level of debt we have accumulated is much higher today than it was forty years ago. Below is a chart of the debt/GDP ratio of the different sectors in the US (government, businesses and households). As a rough guide, government debt and household debt have quadrupled since 1980 while business debt has doubled.

Normally the focus is on the large amount of government debt and how this is going to lead to a catastrophe, but the true weakness lies in business debt. You see, the government can print money to pay for its debt while businesses and households cannot. If the cost of debt rises for businesses and households, they have to either reduce their debt by paying it back (thus reducing profits or disposable income) or they need to spend more on interest, which reduces the money available for investments or consumption.

Debt in the USA

Source: Bloomberg

We have done an in-depth study on the additional debt servicing cost for businesses, households and the government under several scenarios. First, we assume the Fed Funds Rate stays at 3% forever. Second, we assume the Fed Funds Rate stays at 5% forever, and finally, we assume the Fed Funds Rate goes to 10% and then stays there forever. The chart below shows how much money businesses would have to divert from new investments to additional debt service costs (through higher interest rates). The amount increases over time because much of the debt has an interest rate that is fixed for some time, and we assume the interest rate only adjusts upward when maturing debt is replaced. Of course, the businesses could choose not to replace the debt, but that would reduce the amount of money available for investments even more, so the chart below is a best case scenario for debt servicing costs.

How higher interest rates filter through to higher debt servicing costs: The case of US businesses

Source: Liberum

As you can see, higher interest rates for longer would eat up a lot of the money available for investments. If interest rates remain at 5%, about half the money that is typically invested in new projects would need to be diverted to service existing debt. If interest rates go to 10% investment growth would practically be reduced to zero because by 2025 the money would effectively be needed to pay for debt rather than being invested in new projects.

In other words, if the Federal Reserve tries to keep interest rates at 5% or more, then investment growth would drop off dramatically in 2024 and 2025. This, in turn, together with the lower consumption by US households which face a similar problem would lead to a deep recession. And once we are in a recession, the Fed has a hard time justifying rates of 5% or more.

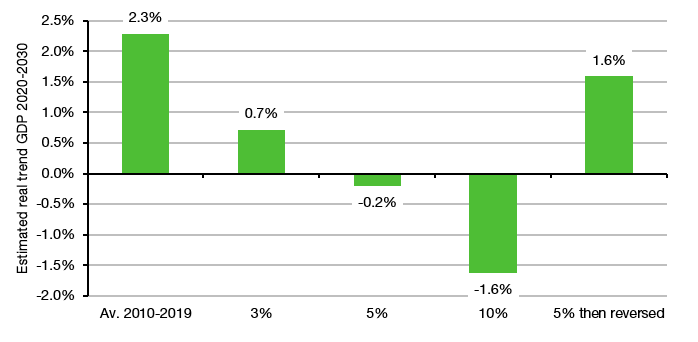

In fact, if the Fed were to remain stubborn and refuse to cut interest rates, trend growth in the 2020s would decline a lot. The final chart shows our estimates for real trend growth in the US for the current decade if interest rates were kept at 3%, 5% or 10% all the time. As you can see, with 5% interest rates, trend growth in the US would drop to essentially zero for the entire decade and with interest rates of 10% it would become negative. Even 3% interest rates would reduce trend growth in the US by about half.

Trend growth in the US under different interest rate scenarios

Source: Liberum

But guess what will happen if the US enters a very long recession in 2023, 2024 or 2025? Public pressure on the Fed will be so large to cut interest rates that it will be impossible to resist. Should a Fed chair refuse to cut interest rates in such an environment, one would have to expect that this person would very quickly be replaced by the President. In other words, the only way forward is one where the Fed keeps interest rates at 5% this year and then drops it back to the 1-3% range. In my view, any persistent Fed Funds Rate above 3% would damage US growth so much that it cannot be defended for more than a year. Our debt load forces us to keep interest rates at very low levels like we have seen it in the 1950s when, not coincidentally, debt was also very high because of World War II.

Obviously, we could be wrong, but the numbers speak a clear language, in my view. We cannot sustain a return to 5% interest rates or more for long and as I mentioned in my introductory note to this series: What cannot happen will not happen.

Nice piece. A central tenet of the argument regarding the 5% scenario seems to be, as you say: “If interest rates remain at 5%, about half the money that is typically invested in new projects would need to be diverted to service existing debt.”

Investment and capital budgeting is typically based on project NPVs. NPVs are typically based on long term costs of capital, which aren’t so volatile and use more normalised risk free rates. Investment that can’t be funded internally gets funded via new debt, equity or hybrid. Hence what do you see as the mechanism by which the volume of investment halves?

Many thanks for the comments and Fernandez paper. I used to read him religiously at UBS.

Reminding myself of your original comment: "If interest rates remain at 5%, about half the money that is typically invested in new projects would need to be diverted to service existing debt. If interest rates go to 10% investment growth would practically be reduced to zero"

So you're attributing the investment impact to NPV effects from discount rate changes rather than free cash flow, which I think makes more sense.

The impact very much depends on the numerator (expected cash flows) and how many projects are at the margin of NPV positive. If 50% of projects were juicy enough (IRRs comfortably above cost of equity) then they'd still be NPV positive and undertaken with a 200bp rise in COE.

I've sent you a LInkedin request. Wld be great to connect.