Most asset management firms tend to have both ESG and non-ESG funds on their product shelf. Often, the ESG and non-ESG funds are managed by the same fund management team or at least managed along the same kind of investment process. Hence, the ESG and non-ESG funds should have similar performance. Yet, if you believe a study (and heads up I have serious doubts about it), then ESG funds in the same fund family get preferential treatment over their non-ESG siblings.

The study authors looked at US-domiciled equity funds and paired ESG funds with non-ESG siblings in the same fund family that match the ESG funds as closely as possible in terms of fees, fund size, fund age, etc. In short, for every ESG fund, they tried to find the closest sibling from the same fund company that isn’t an ESG fund. Then they compared the performance of the ESG with the non-ESG fund.

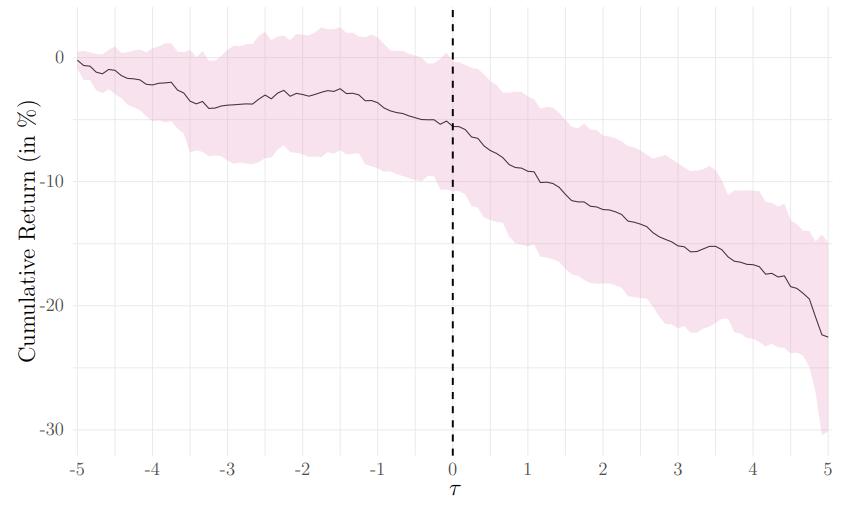

The chart below shows the relative performance of the non-ESG fund vs. their ESG sibling in the five years before the launch of an ESG fund and the five years after the launch. While the non-ESG fund slightly underperformed the hypothetical ESG fund in the five years before the ESG fund was launched, the underperformance of the non-ESG funds accelerated and became much bigger after the ESG fund was launched. In the years after an ESG fund was launched the non-ESG funds from the same fund family underperformed by an average of 14.4bps per month or 1.75% per year.

Performance of non-ESG funds vs. ESG funds of the same family in the ten years around the launch of ESG funds

Source: Csiky et al. (2024)

Note that the performance difference is not due to differences in fees or fund size because the ESG funds were paired with their closest match in that respect.

Instead, the authors of the study claim that the driver of this outperformance of ESG funds may have been favourable stock allocations within a fund family. In other words, strong performing stocks or successful IPOs of new companies may have been allocated preferentially to ESG funds rather than non-ESG funds in the same fund family. The authors claim that by looking at opposing trades (situations where the non-ESG fund sold some stocks and the ESG fund in the same family bought these stocks in the same quarter) this preferential allocation contributed about half of the observed performance difference. A greater exposure to IPOs in ESG funds can explain another large chunk of the performance difference.

If you believe the results of the paper, you might start to suspect that fund managers are manipulating their portfolios to make sure ESG funds have a slightly better performance because ESG funds tend to attract more client money.

However, I have my doubts about this explanation. You see, ESG funds and non-ESG funds are not identical. There will always be small differences in the portfolios simply because the ESG fund will emphasise certain companies more (usually the ones with better ESG characteristics or exposure to an ESG theme) and own lower shares of other companies (typically oil & gas companies).

This is where the period of the examination comes into play. The funds were monitored from 2000 end the end of 2022 with a focus on the period from 2010 to 2020 when most ESG funds were launched.

But during this period, there was a green premium even though that may have been due to other factors than greenhouse gas emissions. And during that period oil & gas stocks significantly underperformed. So, in my view, the performance difference observed in the study is not due to internal subsidies from non-ESG to ESG funds in the same fund family but simply due to green stocks outperforming brown stocks during that time.

Besides, I know quite a few fund managers, and not once did I hear that they shifted stocks from one portfolio to another portfolio to boost performance. Only once have I had direct experience with a portfolio manager allocating stocks to different portfolios based on which portfolios he wanted to boost in terms of performance. And that was in wealth management and the portfolio manager was immediately dismissed the moment the firm found out.

Given the fair-trading policies in place in almost all fund management firms giving one fund preferential treatment over another would be a sackable offense and in most countries outright illegal. So, let’s not jump to nefarious conclusions when a simple explanation works as well. And the simple explanation is just that green stocks outperformed brown stocks and that created a performance gap between ESG funds and non-ESG funds in the same fund family.

I held my breath until the very last paragraph where you mention that preferential IPO share allocation is something fund management firms police very tightly internally.

A broader issue for another study I really wish someone would perform is whether IPO participation is even an advantage over the longer haul.

Investment banks have always implicitly sent the following message to institutional clients: The more you churn your portfolios, and the more trading commissions you generate, and the more of those commissions you disproportinately direct to us, the higher your allocation of the next hot IPO we manage will be; you'll promise to be long-term holders, but then you'll inevitably flip some or not all of it on the pop, and boost your outperformance relative to benchmark and competitors; wash, rinse, and repeat. The don't call it "the sell side" for nothing!

However, my gut feeling is that, on average, IPO stocks tend to underperform the market in the three to five years following their debut, suggesting that funds relying heavily on IPO allocations may see short-term boosts but struggle to sustain outperformance. Success stories of companies like Amazon and Google create a perception that IPOs are great investments, but many IPOs (especially outside of tech) have struggled or even collapsed (WeWork, Blue Apron). The Renaissance IPO ETF has trailed the S&P 500 in multiple periods, illustrating the challenge of making IPO investing a consistently winning strategy https://www.google.com/finance/quote/IPO:NYSEARCA?window=MAX .