Can central banks still target inflation?

One of the mysteries of the last decade is why, despite the strong recovery in the job market and the economy overall, inflation has remained stubbornly low in most Western countries. This conundrum reminds me of the jobless recovery after the 2001 recession. Back then, central banks saw the economy recover after the recession and inflation rise but job creation remained remarkably sluggish for many years. The result was that central banks in the US and Europe left interest rates too low for too long and helped fuel the housing bubble that led to the Global Financial Crisis.

Today, we have the reverse image of this conundrum insofar as job creation remains strong but inflation, and in particular core inflation and wage inflation remain low. Traditionally, low inflation is explained by underutilized resources in the local economy as well as frictions in adjusting wages etc. A commonly stated reason for the low wage inflation, for example, is the decline of unionisation and thus bargaining power of workers.

But what if the true reason for the stubbornly low inflation in the last decade is not domestic but global in nature? There has been a lot of talk about globalisation and how global supply chains and the shift of production from developed to emerging markets has kept production costs low. As a result, there is little reason for companies to pay higher wages domestically, since they can simply use workers in emerging markets or machines to do the work.

Interestingly, such globalisation effects are typically not reflected in inflation models and if they are, then typically only in the form of import prices. However, globalisation may influence inflation through many different channels, only some of which are captured by import prices. First, as supply chains become more global, exchange rate fluctuations have an increasing impact on input prices for producers. Exchange rate fluctuations, on the other hand, are predominantly driven by international differences in economic growth and interest rates. Hence, in a more globalised world the weakness of one economy can develop a significant influence on the inflation in another country with close trade relationships. Given the close trade relationships between the US, China and (to a lesser extent) Germany, a disinflation and slack in the Chinese economy could lead to lower inflation in the US and Germany.

Second, increased globalisation means increased global competition so that domestic producers face challenges from foreign producers. Thus, even though domestic producers may face higher wages and rising input costs, they may be increasingly unable to pass these higher costs on to end consumers due to the cheap competition from emerging markets, for example. This would imply that volatility in producer prices cannot be passed on to core consumer products and services.

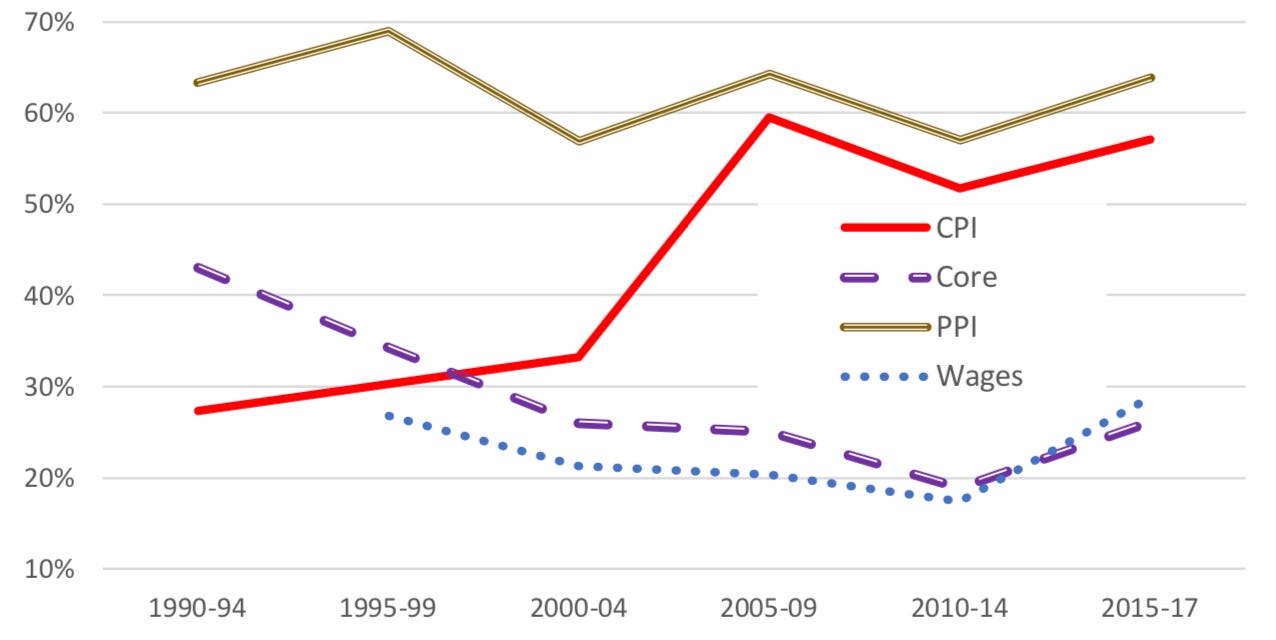

To test if globalisation lead to lower inflation over the last decade, Kristin Forbes from MIT has checked how much of the variation in inflation can be explained by international factors such as commodity prices, exchange rate fluctuations, trade integration and global supply chains. The chart below shows one of the key results of her paper. The share in variation of consumer price inflation (CPI) in 43 countries explained by global factors has more than doubled from 27% in the 1990s to 57% over the last five years. This indicates that globalisation is playing an increasingly important role in the variation of inflation.

Meanwhile, core inflation and wage inflation, on the other hand remain largely determined by domestic factors. This makes sense if core and wage inflation is not so much driven by import price inflation but the ability of domestic firms to pass on higher costs to end consumers. If globalisation leads to increased competition from foreign businesses, then core inflation and wage inflation may look like it is still influenced only by domestic factors but only because domestic businesses are unable to pass on fluctuations in costs to end consumers. Producer price inflation (PPI), on the other hand, has always been significantly influenced by global factors because this inflation measures the prices of goods that are used in global trade and global supply chains.

Share of inflation variation explained by global factors

Source: Forbes (2019).

What does this mean for central banks and monetary policy?

On the one hand, there is increasing evidence that globalisation has played a key role in keeping inflation low over the last decade. On the other hand, this also means that central banks are increasingly unable to target inflation simply because many of the factors that drive inflation are beyond their control. Central banks are unable to fix exchange rates or control inflation in China and other emerging markets, so they are increasingly powerless to control inflation in the US or Europe.

And now imagine that the global disinflation trends we have seen over the last decade start to wane or even reverse. What if wage pressures in emerging markets lead to rising inflation there, that then puts increasing price pressure on the cost of goods produced in a global supply chain? What if emerging market currencies crash in a recession and trigger high inflation (e.g. through higher commodity prices) in these emerging markets? Could it be that this emerging market inflation then spills back into developed markets? What if a developed country runs increasing fiscal deficits that trigger a decline of its currency and thus an increase in inflation locally that then spills over to other developed markets?

There is inconclusive evidence so far that these mechanisms could lead to a significant spike in inflation, but it could be that central banks are less and less able to fight inflation should it ever rear its head again. So far, we don’t have to worry about that because inflation remains stubbornly low, but it could be that monetary policy is not only increasingly unable to fight a recession, as I have pointed out here, but may also increasingly become unable to fight inflation. It is not the death of monetary policy (yet), but certainly a case of deteriorating health.