Bringing a knife to a gunfight

I have recently written about my suspicion that in most developed countries debt levels have become so high that cutting interest rates or starting a new round of quantitative easing may well lead to lower growth in the medium term.

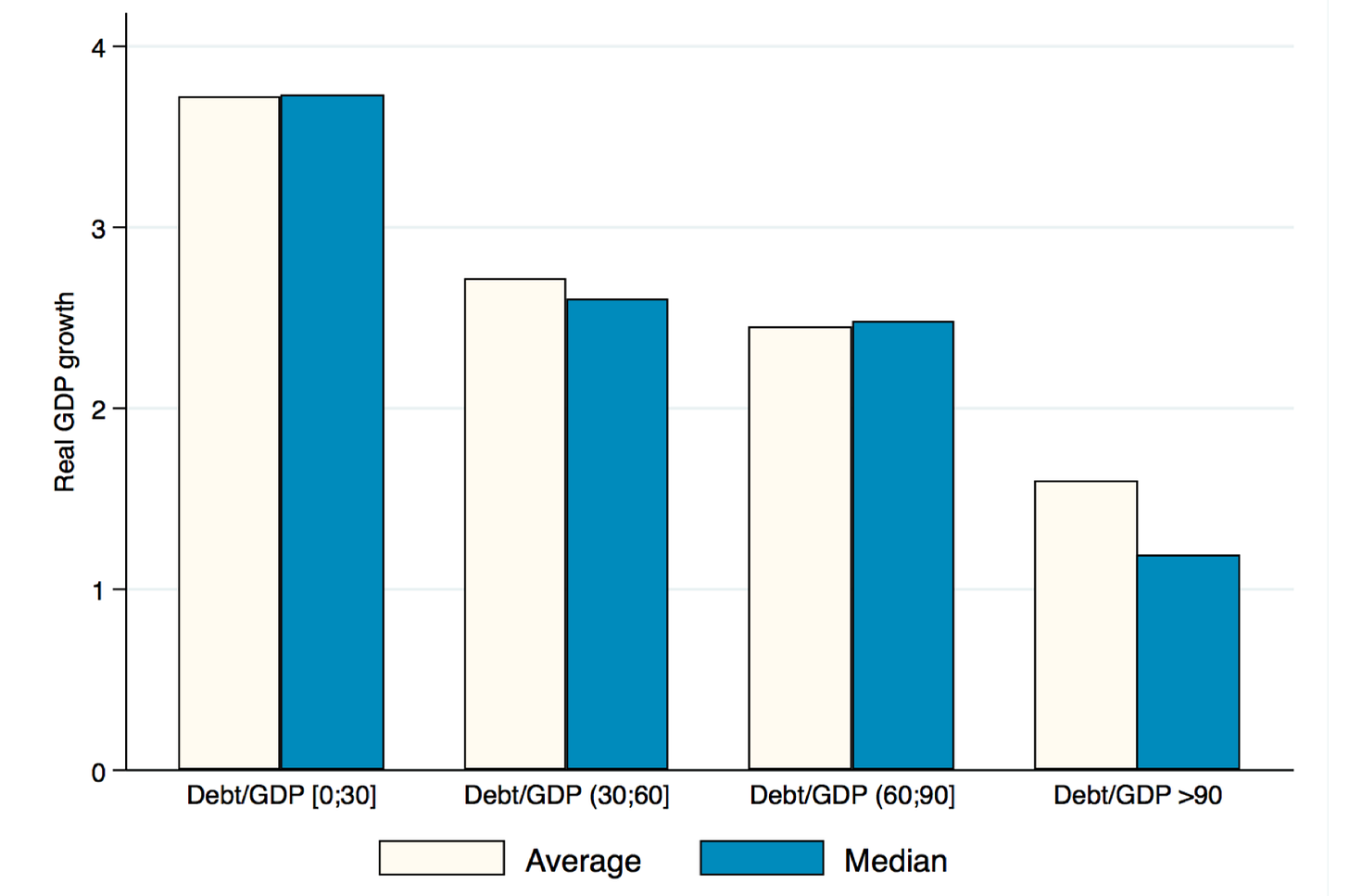

Historically, there has been a link between government indebtedness and future GDP growth, which was popularized by a 2010 paper by Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff. The paper came under intense scrutiny later on when an Excel error was discovered in their analysis but the chart below shows a recent independent verification with data until 2016 and from a different source. It shows qualitatively the same picture of lower growth in times of higher debt/GDP-ratios.

The problem is that not all debt is created equal. We know that governments can run fiscal deficits for good and bad reasons. Good reasons are:

Investments in public infrastructure and other public assets

Countercyclical fiscal stimulus to dampen a recession

Tax smoothing in the face of unexpected expenditures (e.g. natural catastrophes, wars etc.)

In contrast, bad reasons for public deficits are:

“Political stimulus” to get politicians re-elected

Spending of public monies to benefit a small interest group (e.g. a specific industry or wealthy individuals)

Intergenerational transfers away from future generations to current recipients (e.g. through a generous social safety net)

In recent years, politicians both on the left and the right have engaged or promised to engage in deficit spending that falls firmly in the camp of “bad reasons to increase the deficit”. In the US, the positive effects of the Republican tax cuts of 2018 have largely evaporated by now and we are left with an economy that is running at full steam and at the same time accumulates more than $1 trillion in new government debt each year. In the UK, years of austerity have clearly come to an end as government borrowing has increased 7% year-on-year in June and is on track to surpass last year’s deficit by more than one third. The Office of Budget Responsibility estimates that in the case of a no deal Brexit the deficit could nearly triple in the 2020/2021 fiscal year from last year’s levels.

Yet, politicians on the left argue that they need to spend more on helping the poor and expanding healthcare and other benefits while politicians on the right argue that lower taxes and smaller government are the answer to our problems. In the case of a hard Brexit, for example, a Boris Johnson government in the UK may well cut corporate tax rates dramatically to emulate the example of Singapore. Meanwhile, in the US the Democratic candidates for President all endorse one form of public healthcare or another without going into too much detail how this should be financed. It is as if both sides of the political divide are stuck in old dogmas about taxation and public spending that have been rehashed since the 1980s.

But in 1980, the UK had a debt/GDP-ratio of 45% and a budget surplus of 1.0%. In 2018, the debt/GDP-ratio was 87% and the deficit was 1.5% of GDP. In the US, the situation is even worse because in 1980 the debt/GDP-ratio was 32% and the deficit was 2.5% of GDP. Today, the debt/GDP-ratio is 104% and the deficit is 3.8% of GDP. Am I the only one who thinks that it makes a difference for the efficacy of fiscal stimulus if you start with a small pile of debt or a large pile of debt?

Of course, politicians are always able to find an excuse why deficits may not matter that much. The current darling of politicians on both the right and the left is Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). I have written about that topic here, here, and here so I won’t go into that topic here.

But what worries me is that the increased deficits of recent years will reduce our ability to fight the next war. If my suspicion of the negative effects of lower interest rates on growth are correct they will exacerbate the negative impact that the high levels of debt have on future growth. And these effects, in turn will limit our ability to spend in an emergency.

Historically, the costliest emergency that has befallen advanced economies are wars and I think we need to prepare for another war effort. Just this time it is not going to be a war against other nations or terrorists. This time it is going to be a war against climate change.

Last year, the UN PRI published a report on The Inevitable Policy Response. In it, it argued that the longer we wait with our efforts to adapt to climate change (note here that I don’t talk about mitigation because in my view it is already too late to halt climate change) the more expensive and disruptive it will be. The longer we wait, the more emergency measures we have to take to build dams against rising seawater levels and pay for the damage caused by hurricanes, droughts and flooding.

Since 2005 the cost of emergency funding from weather and climate related disasters in the US has summed up to $500 billion. But that is likely going to be pocket change compared to the sums necessary to adapt to climate change in the future. In fact, it is likely to cost the US trillions of dollars to protect its coastlines against sea level rise and storm surges alone. And nobody knows how much it will cost to adapt to declining crop harvests and the damages from wildfires etc. In short, fighting climate change will cost us similar amounts to fighting another world war. And if we continue to behave as if deficits don’t matter or look for excuses why deficits can be run almost indefinitely (e.g. MMT), we are limiting ourselves to a knife when we are going to get into a gunfight.

Government debt and growth in advanced economies 1960 - 2016

Source: Global Debt Dataset (Mbaye et al. 2018), IMF World Economic Outlook.