I always warn readers of long-term projections for the economy. The uncertainty grows with the time horizon and the results depend heavily on the assumptions made in the model as I have described here. Keeping these limitations in mind, I think that new research from the University of Groningen warrants a closer look because it shows the declining importance of Europe and North America for global trade.

One of the main drivers of economic growth and global trade is the share of the working age population in a country. If a country has a larger share of working age people, it has more workers and can produce more stuff, thus creating higher economic growth.

However, a country with a higher labour supply also tends to have lower wages for a given level of productivity. The main driver of wages remains productivity with more productive industries paying higher wages, but once accounted for, wages tend to decline if labour supply increases.

In Europe, we have come to an inflection point. Until 2020, the share of working age population in Europe was higher than the global average. Going forward, it will be lower because of the ageing demographics. This means that Europe no longer benefits from a demographic dividend and faces rising wage inflation to deal with the declining labour supply. The demographic dividend has moved on to India and will again move to Africa in 2050.

Working age population (15-64 years) as share of the total population

Source: Brakman et al. (2024). Note: EUR = Europe, IND = India, AFR = Africa.

How are trade flows going to react to this? Most global businesses focus their production of goods and services in countries with lots of qualified people to hire. This means that trade moves in the direction of countries that have a larger working age population. It also tends to move away from countries with declining working age populations.

What the new research did was to estimate how much of global trade will be centred around Europe, North America and other regions in two scenarios. One where only the demographics change, but national income and productivity remain unchanged, and another where demographic change leads to changing trade patterns, which in turn increases the wealth and productivity of receiving countries over time.

Likely, increased participation in global trade leads to the import of more productive technologies and as a result increases GDP growth and GDP per capita over time. This is what we have seen in every country that developed its industrial base since the Second World War, whether it is China, India, or any of the Asian Tiger countries. The question is not whether increased participation in global trade improves productivity and income, but by how much. This is where the large uncertainties come into play.

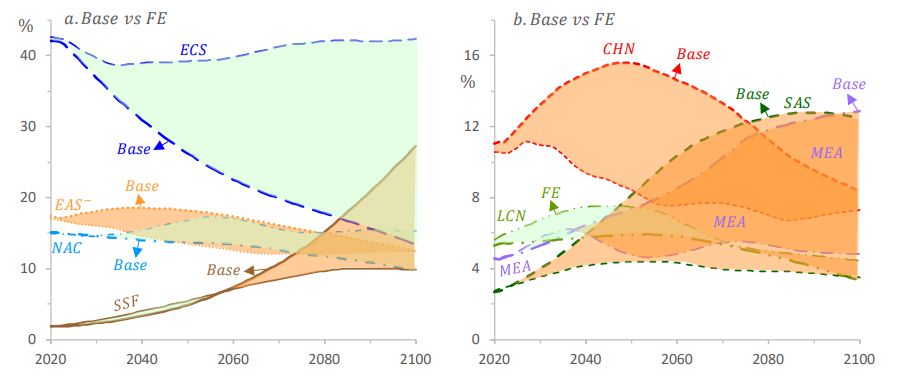

The charts below show the projections for shares in global trade purely from demographic effects and the base scenario for the dynamic effects of increased trade on productivity and income.

Regional trade projections

Source: Brakman et al. (2024). Note: Thin lines only reflect demographic changes, Base case includes also changes in productivity and income. ECS = Europe and Central Asia, NAC = North America, EAS- = East Asia ex-China, SSF = Sub-Saharan Africa, CHN = China, SAS = South Asia, MEA = Middle East and North Africa, LCN = Latin America and Caribbean.

Currently, trade is centred around Europe with some 42% of global trade involving at least one European country. The ageing demographics of Europe mean that this share is likely to decline somewhat towards 40% and a little below before recovering again after 2050. But if we take productivity and income effects into account, Europe will likely lose its status as the global centre of trade and see its share in global trade drop significantly to well below 20%. It will still be bigger than North America, but only barely so.

Meanwhile, the two big winners are likely to be South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Demographic effects alone will increase the global trade share of Sub-Saharan Africa from 2% today to 10% in 2100. But if the increase in productivity and income is included, the projected share in global trade rises to 27% turning Sub-Saharan Africa into the world’s most important trading hub! South Asia, meanwhile, could see its share in global trade rise to 12%, on par with Europe.

2100 could look very different from today indeed, with a quarter of global trade centred around Sub-Sharan Africa and Europe, North America, the Middle East, South Asia, and East Asia ex China all hovering around 10-15%. China could be a small player at less than 10% of global trade and Latin America even less important than it is today.

Of course, that ignores any shifts in global trade due to the trade war and the geopolitical decoupling underway right now, but qualitatively, I would expect that this geopolitical decoupling should benefit countries in South Asia and Southeast Asia as well as Africa the most since they tend to be ‘neutral’ in the rivalry between China and the West. It looks as if the future of trade is in Africa and Asia, not Europe and North America.

Very important topic, thanks!

* Predictions to 2100?

* Demography is destiny, but China's is worst of all, and India ain't too good, either

* Africa looks good if it gets its free trade zone thing together. Good luck with that!

* re Peter Zeihan, USA still looks best to 2050 because demography+ attractiveness for immigration + educated work force. This has considerable investment implications, at least for me.

the US is the one in the best position in my opinion. And again in my opinion Africa has no chance of getting out of the black hole in which it finds itself, especially considering the climate changes that are already devastating; even if in Western and Northern Europe you don't notice it, in the South we are starting to notice it seriously