Trump is back in the White House and with him comes a renewed push to decouple the US from China and other political adversaries. In Europe, meanwhile, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has led to decoupling and reordering of many supply chains. But how does this deglobalisation trend pan out? Fascinating research from the ECB provides some key insights that I want to discuss in two posts. Today, I will focus on how deglobalisation is happening. Tomorrow, I will talk about its impact on prices and inflation.

I cannot stress enough what a treasure trove the paper by Ivelina Ilkova, Laura Lebastard, and Roberta Serafini is. I think everyone interested in global trade and its influence on inflation should read it to see what kind of baloney some economists and investors are spouting about global decoupling leading to lower inflation (more on that tomorrow).

First, let’s look at the reality of deglobalisation. The authors look at changes in global supply chains for key products (including strategically important goods, minerals, etc.) in the Eurozone and the US between 2016 and 2023. This period covers both Trump’s first term in office and the fallout from the Ukraine war and the global supply chain disruptions of 2022.

There are basically two ways how businesses can react to global supply chain risks. First, they can decouple from certain suppliers and relocate production to their home countries (backshoring) or to politically friendly countries (friendshoring). Second, they can diversify global supply chains to be less reliant on a single manufacturer or country (note that this could mean diversifying from one political adversary to another political adversary).

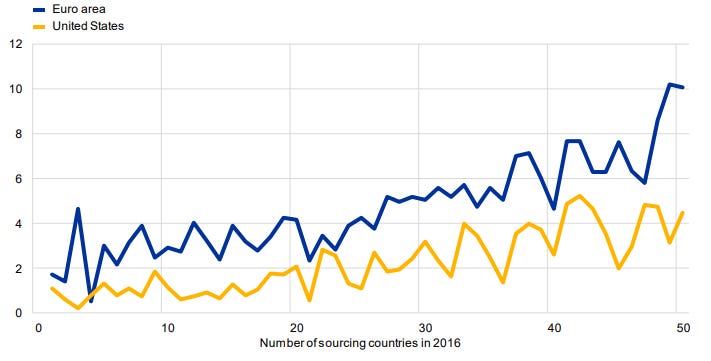

What definitely has been happening is the diversification trend. The chart below shows the increase in a number of sourcing countries between 2016 and 2023 in the Eurozone and the US. The more diversified a supply chain was in 2016 the more the number of sourcing countries has increased, but in general, the number of sourcing countries has increased everywhere and for almost all imported goods, particularly in the Eurozone.

Change in number of sourcing countries 2016 to 2023

Source: Ilkova et al. (2024)

As for the decoupling trend, the evidence is more mixed. The chart below shows the changes in shares in the Eurozone’s import market between 2016 and 2023. As you can see, the import share has declined massively for Russia and the UK. The former was a result of the Ukraine war, and the latter was a result of Brexit. But while the Eurozone has decoupled from these two countries it has increased its ties with China. No sign of decoupling there. Similarly no sign of the Eurozone decoupling for other Asian countries.

Change in share of Eurozone import market 2016 to 2023

Source: Ilkova et al. (2024)

Now compare this to the US below. Here we see a clear decoupling of US supply chains from China and Russia in favour of closer links with Brazil and other Latin American countries but also France and Spain. And there has been an increase in the import share from geopolitical adversaries like Zimbabwe, the DRC, Vietnam, and others. Once again, a rather mixed picture.

Change in share of US import market 2016 to 2023

Source: Ilkova et al. (2024)

What this research shows is what I and others have been arguing for a long time. Most businesses cannot simply decouple from supply chain hubs like China. It takes many years to do that, and it is often too expensive to justify. Hence, the only decoupling trends that are somewhat meaningful are the decoupling of the US from China and the decoupling of the Eurozone from Russia and the UK. And at least when it comes to the decoupling of the Eurozone from the UK, that trend may reverse if the current UK government is successful in its efforts to move closer to the EU again.

Taken together, the data tells me that the world is not in a deglobalisation trend but in a derisking trend where diversification of supply chains leads to new investments in certain areas like Southeast Asia that in the past would have been made in China or Russia.

If I understand what the map is showing is the US is importing less from NAFT counties Canada and Mexico which is counter intuitive. Why would that be?

there seems to be an opposing force with respect to excess global industrial capacity.

but perhaps the simple answer is that the lowest cost supplier will be selected within trade clusters, even if a much cheaper option exists elsewhere?

https://hoisington.com/pdf/HIM2024Q4NP.pdf