If you are younger than 65 right now and live in a developed country, you have a problem. On the one hand, you know that your society is aging rapidly and that means that the dependency ratio (i.e. the number of working age people who have to finance pensioners) increases rapidly. This will either lead to a reduction in social society and pension benefits over time or to higher taxes on both the working age population and pensioners. Either way, your expected net income after taxes declines, and your lifestyle is increasingly threatened.

The two ways to deal with this problem are either to accept a lower income and a reduced lifestyle or to save more. But with central banks introducing zero interest rates everywhere, saving more has become increasingly difficult because even if you are able to save more today, the savings just aren’t growing like they used to.

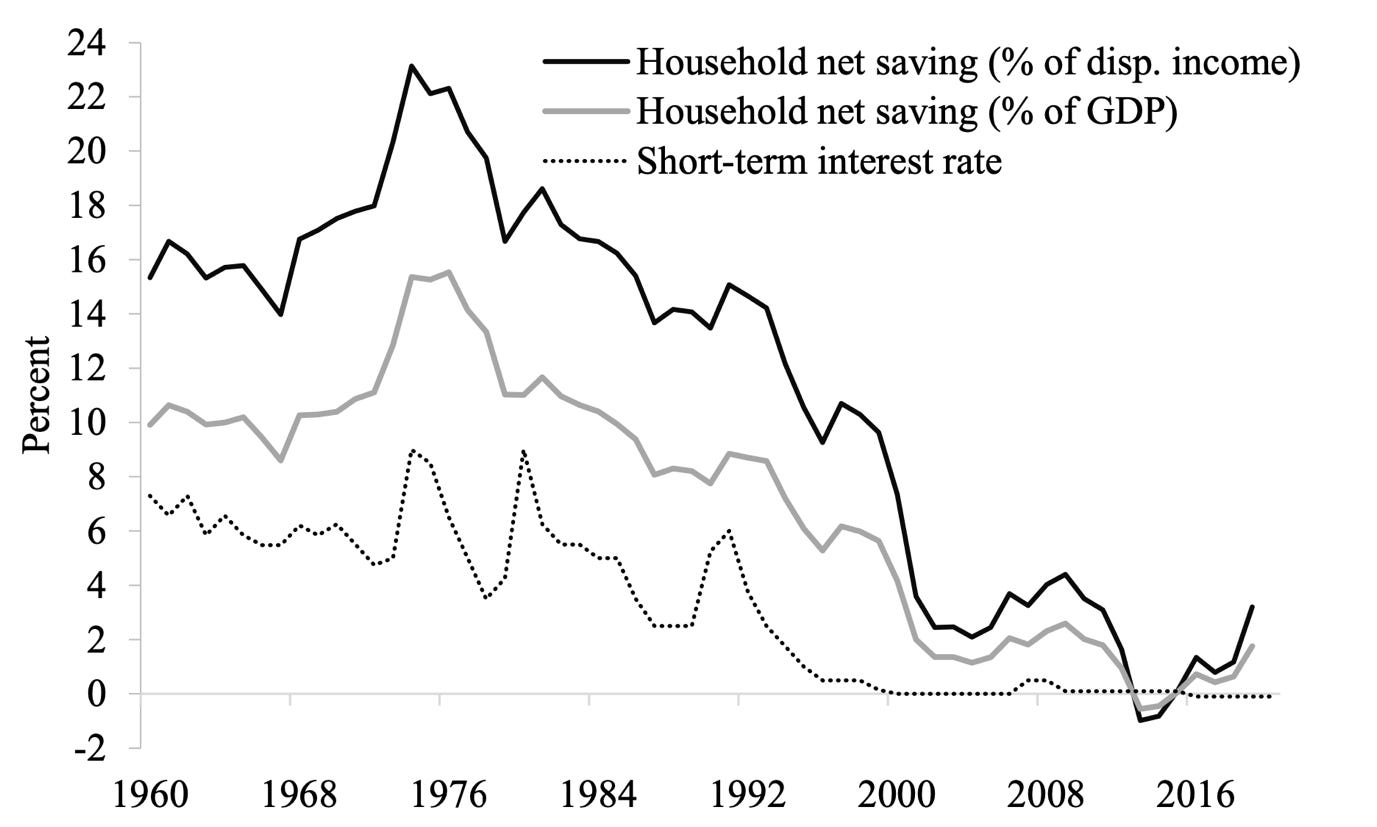

It is not clear which one of these forces will win in the end, the incentive to save more due to an ageing society or the incentive to save less due to lower interest rates. In this respect, studying the example of Japan, which has a head start of about two decades on the situation in Europe and the United States can be very informative. And when it comes to savings behaviour, the verdict is pretty clear. After two decades of zero interest rates, savings rates in Japan have plummeted.

Savings rates and monetary policy rates in Japan

Source: Latsos and Schnabl (2021).

I find it hard to believe that the outcome in Europe or the United States should be any different. People really don’t like to save for the future and if the incentive to do so is reduced through lower interest rates they are all too willing to spend their money today, rather than save for tomorrow.

The problem of course is that this aggravates the problem for pensioners since they now face an ageing society and lower savings than their parents and grandparents. The Japanese are solving that problem in a very simple way. They have managed to turn around the trend in the dependency ratio. Since about 2015, the dependency ratio is declining again in Japan.

Dependency ratios in Japan are declining again

Source: Latsos and Schnabl (2021).

The solution in Japan is simply that the employed population is growing fast again. And no, it is not through higher immigration, but through older people re-joining the workforce at age 65 or older.

Obviously, this is not some romantic version of being active and productive in old age. Most of the time, older Japanese have to go back to work in some minimum wage jobs just to make ends meet. And with more and more older people being forced to go back to work the wages for these jobs are coming increasingly under pressure. Japan faces an increasing income inequality without any meaningful immigration or outsourcing of manufacturing jobs to emerging markets. I wouldn’t be surprised if, in ten or twenty years, we in Europe and the United States would face the same problems. And I wonder how populist politicians will blame them for the lack of opportunity and income growth of the working class.

Of course, demographics is NOT destiny, as I always say, so the example of Japan is not a necessary result of the current developments in Europe and the United States. But we better start thinking about solutions to this problem today, to be able to fix it. Because it will be pretty hard to manage rising income inequality and declining real wages if you can no longer blame outsiders for your problems but have to pit different parts of your own population against each other.

Joachim do you think that the effects of climate change on proximate regions will lead to a markedly different outcome than experienced in Japan? The Japanese are notoriously averse to immigration and as an island nation they have the luxury of vast seas to keep unwanted immigrants out. The US and Europe, on the other hand, are connected by land to continents which may be the source of large numbers of emigrants due to cities and regions becoming increasingly inhospitable due to climate change causing heightened water stress, agricultural degradation, prevalence of disease and hotter nights.

You have not even included the big one: automation! The declining opportunities will differ on function and industry but will all contribute to an even greater decrease in the ratio of available dependence.