Greenwashing everywhere

I have recently written about the lack of consistency amongst providers of ESG ratings on stocks. This chaos amongst ESG ratings of different providers and the lack of transparency of the criteria different providers use to rate companies on ESG risks has been identified in a recent study by SCM Direct as a main source of the greenwashing pandemic in mutual funds.

The study, which has become prominent thanks to an article in the Sunday Times, looks at the practice of different mutual funds that claim to follow a sustainable investment approach. Now, with the ratings chaos, this is always going to be difficult since, as the study of SCM Direct shows, companies like Tesla have a very different ESG rating depending on how rating agencies treat information that is not disclosed by the company. Undisclosed information is given the lowest possible score by FTSE, leading to a very low overall score for Tesla, while MSCI ESG or Sustainalytics typically assume a company that does not disclose certain information has practices in place that match the industry average – thus creating a much better ESG rating for a company like Tesla.

Tesla ESG ratings by rating agency

Source: SCM Direct, Wall Street Journal.

And these differences in the treatment of undisclosed information leads to differences in the portfolio composition of funds. A fund manager that uses exclusively FTSE ESG ratings would likely exclude Tesla from her portfolio, while a fund manager who uses MSCI ESG or Sustainalytics would include it.

These differences amongst ratings approaches together with different processes of fund managers to the inclusion of stocks mean that many sustainable investment funds can have large allocations to sin stocks like tobacco, defence, and others. And this is where the SCM study overshoots its target, in my view.

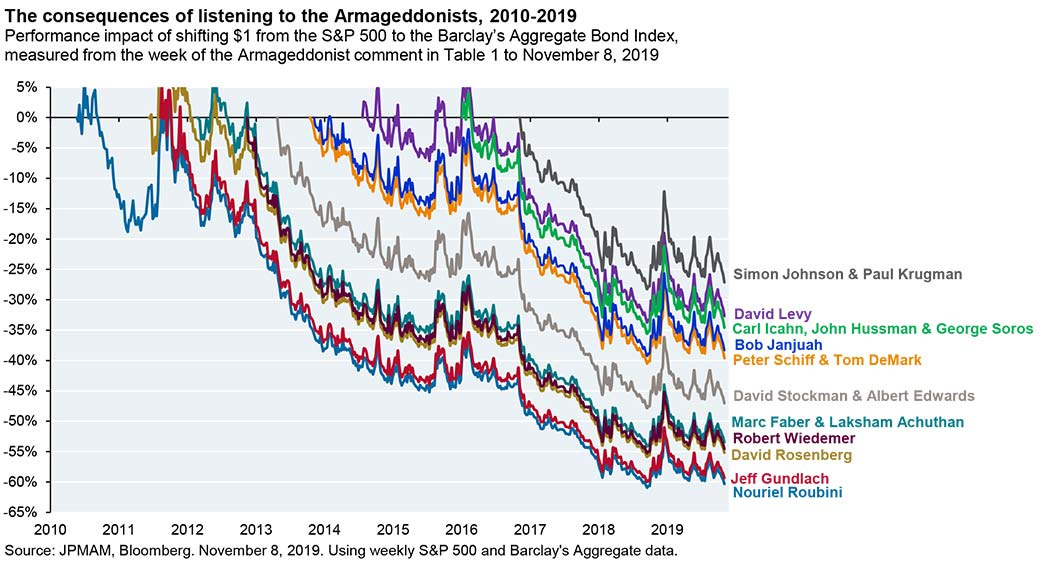

If you think of ESG investing solely as a method to avoid investments in defence contractors or tobacco companies, you have not understood what ESG investing is. ESG investing is an approach to manage risks emanating from polluting the environment, violating social standards like labour laws and faulty governance. And the right way to manage risks is not to avoid them altogether. If we would do that, we would simply hold cash or highest quality money market investments in our portfolios. And JP Morgan has recently shown the damage such an approach can do to your portfolio.

Instead, managing risks means accepting some risks, diversifying these and then monitoring them so that if these risks materialize, they do only limited damage to the portfolio. As such, the better way to create sustainable investment portfolios is a best in class approach, where companies are selected based on their risks relative to other companies in their sector or industry. Such a best-in-class approach inevitably means that you will end up with tobacco companies and other sin stocks in your portfolio. But it will reduce your overall portfolio risk compared to a traditional portfolio and provide an incentive to companies to improve their ESG ratings.

If companies know that more funds will invest in their stocks if they get a better ESG rating, then they will aim to improve their rating over time. If they think that no matter what they do, their industry will always be excluded from these portfolios, then why bother with ESG risks at all?

Similarly, the authors of the SCM Direct report complain that UK and US government bonds are considered sustainable or even ethical investments despite the fact that both countries are nuclear powers and have a sometimes checkered track record in international politics. But compared to government bonds from many other countries, the US and the UK have working democracies (at least so far) and checks and balances for politicians in power.

Nevertheless, the SCM Direct report does make some great points. Sustainable investing needs a universal definition and clearly defined concepts that are regulated by government authorities rather than based on the approaches of individual rating providers. Otherwise, there is too much incentive to game the system and declare a fund to be sustainable even though the managers have hardly changed their investment process compared to a traditional fund.

ESG risks need to be taken seriously, and fund managers need to put these risks at the same level as the market, credit and counterparty risks if they want to call their fund sustainable or ethical. Furthermore, funds need to clearly explain to their investors how they manage ESG risks and what they mean by sustainable.

Otherwise, we end up with the opening example of the SCM Direct report. They searched the Fidelity fund database for all funds managed by the company that are labelled socially responsible funds. The 49 fund share classes that showed up were all but socially responsible. Only two funds stated in their KIID that their investment process reflects ESG criteria. In a different database, the search for socially responsible funds provided by Fidelity created a list of five funds, none of which managed their portfolios with an emphasis on ESG risks. No wonder, Fidelity switched off the ability to search for socially responsible funds in their database after the article in the Sunday Times was published, but that certainly isn’t the solution to the chaos of ratings and the greenwashing of so many traditional funds.