Investing in demographics is a stillbirth

Today, my book goes on sale and if you have pre-ordered a copy, you should have it in your mail soon. If you haven’t bought the book, let me ask you:

WHY?

You can still rectify this terrible mistake by going to Amazon or my publisher Harriman House.

One of the chapters in the book is dedicated to a mistake that is particularly common when trying to invest in trends and themes. As I show there based on examples from the IT and tobacco industry, investors and analysts typically focus too much on one side of the equation that determines prices. Either, they focus predominantly on a demand trend or a supply trend. Much effort is made on predicting this long-term shift in demand and if the shift is strong enough, the investor or analyst comes to the conclusion that this will be an exceptional investment opportunity that will drive profits for companies exposed to this trend. This kind of thematic trend examination is particularly popular in brokerage firms where the analyst has to convince his clients to buy or sell stocks (because that’s how they make money) and in think tanks and consulting firms where a megatrend will likely lead to increased consulting work. But this kind of thematic trend investing has also become increasingly popular in private banking and retail investing where investors are invited to buy a growing number of thematic ETFs and funds.

Don’t get me wrong, I love thematic investing and if done right, I think it is one of the best ways to identify long-term investment opportunities. However, to do it right, one needs to look at more than just a shift in demand alone. Prices are determined by the balance of supply and demand and all too often a thematic trend on the demand side is overwhelmed by another shift on the supply side or vice versa.

An example that isn’t in my book is demographic change. Since we entered a new decade a month ago, I saw several private banks and asset managers tout that demographic change will be a dominant investment theme in the 2020s. The arguments are always the same: The baby boomer generation is retiring and the ratio of young people to old people is increasing. And because the ranks of the elderly and retired are growing fast the businesses that cater to the needs of this demographic will see faster growth in the future. I have succinctly expressed my views on this thesis in my predictions for the coming decade, but let me explain it in more detail.

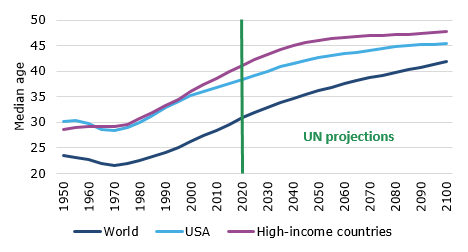

Let’s first look at the demand for products and services for the retirees and the elderly. The chart below shows the median age of the global population together with the United States and high-income countries overall. The median age of the global population is 30.9 years, while in the United States it is 38.3 years and in high-income countries 41.0 years. Thanks to higher immigration rates, the United States had a younger population than other high-income countries since the 1990s. Over the next ten years, the median age is expected to increase by 0.7% per year globally, and by 0.5% in the United States and high-income countries.

Median age of population

Source: UN World Population Prospects 2019.

As a first approximation global demand is driven by the total number of people, their average income and their consumption basket. Population growth is typically in the order of 1% globally and expected to slow down to 0.9% in the 2020s. In the United States, population growth is expected to be around 0.5% and in high-income countries, it is expected to be around 0.25%. Meanwhile, growth in real income per capita is typically around 3% globally, in the United States around 2% and in high-income countries overall around 1.5%. The shift in the average consumption basket can be approximated by the change in median age of the population.

What these numbers show is that investors are trying to benefit from a trend (demographic change) that is completely overwhelmed by the growth in income and its fluctuations. Real per capita GDP growth is about two to three times greater than the annual shift in the consumption basket due to demographic change. Furthermore, the variability of income growth (aka the economic cycle) is about three to four times larger than the trend these investors are trying to benefit from. In this case, the noise completely dominates the signal.

But instead of looking at the population overall, the case for investing in demographic change hinges on the fact that older people have higher growth rates than the population average. The chart below shows the 10-year average annual growth rate for people aged 65 and over since 1960 together with the projections until 2100. Every data point shows the average growth rate in the decade running up to the year the data point is plotted. Hence, the average annual growth rate of people aged 65 and over has been 2.3% globally, 3.0% in the United States, and 2.3% in high-income countries. Over the next ten years this growth rate is expected to decline to 1.9% globally and remain constant in the United States and high-income countries before dropping quickly afterwards. The acceleration in demand from older people is already behind us and has taken place over the last decade (which coincidentally is why I first wrote about demographic change in the mid-2000s). Did anybody notice an effect on the companies that are supposed to benefit from demographic change? Has anybody outperformed the stock market over the last decade by investing in funds and stock baskets that were designed to benefit from demographic change? If not, what makes you think that these investments will do better in the future than they did in the past?

Growth of population aged 65 and over

Source: UN World Population Prospects 2019.

Finally, and this is the point I make in my book at length, let’s investigate how supply shifts in reaction to this change in demand from older people. If we want to benefit from demographic change then population growth of older people has to be higher than growth in the rest of the population. This excess growth of older people leads to excess demand for products and services catered to them. The chart below shows the annual excess growth rate of people aged 65 and over versus people aged 64 and under. The chart is practically the same as the chart above showing an acceleration in excess growth over the last decade that now remains stable in the United States and high-income countries before declining in the 2030s and beyond. Again, demand by older people is growing faster than demand by younger people but this excess growth is slowing down which implies that the demographic trends are weakening, not strengthening.

Excess growth of population aged 65 and over versus people aged 64 and under

Source: UN World Population Prospects 2019.

Furthermore, the growth of the older population as well as the excess growth are so small that it is easy for companies to adjust to this slow change in demand patterns. Everybody knows that there are more and more older people, so it is easy to prepare for this trend by building more care homes, specialising in the development of drugs for Dementia and develop package holidays for older people. While it may take a decade to develop a new drug, an elder care home can be built in a year or so and package holidays and entertainment offerings for older people can be designed and brought to market within a year or less. While demand shifts due to demographics happen over a decade or more, supply can adjust in a fraction of the time. And this means that by the time the demographic shift has happened there is already a highly competitive industry that caters to it. And as everywhere, the more competitive an industry is, the lower the profit margins get.

In fact, in case of demographic change the very investment proposition may be self-defeating. The more money is invested in companies and ventures that cater to an ageing society, the more competitive this segment of the economy will get and the less profitable these ventures will eventually be. This is a recipe for underperformance, not outperformance. Yet, no institution or analyst who touts demographic change as a major trend has ever looked at these supply effects as far as I can see. As I mentioned above, I have been writing about demographic change myself about 15 years ago or so and admit to making the same mistake then. This is why I have written my book. Over the years, I have learned from this and other mistakes and developed techniques to avoid them. I hope that my book will help you avoid these mistakes as well.