It really is the dismal science

When I am in a dark mood about my profession, I tend to say that economics isn’t really a science. Unlike the hard sciences, it doesn’t have laws and there is no established way to apply the scientific method or falsify a theory (in the Popperian sense). Instead, you can always find a time frame over which a theory seems to work or you can wilfully misunderstand a theory to show its validity even though it is by now consensus that a given theory is at least incomplete (as these guys have done).

But economics isn’t a hard science, it’s a social science and has to deal with those pesky subjects of inquiry called humans. And humans change their behaviour all the time, so it is likely impossible to formulate immutable laws of economics, with the possible exception of the law that everything changes all the time in economics.

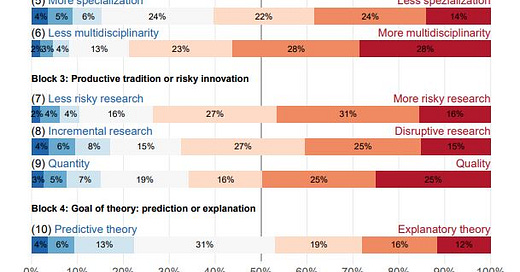

But this fluidity also means that there is no real consensus about what is important in economics and which areas should be researched and which areas can be ignored or are less important. What’s more, economists can’t even seem to agree on what kind of research is good research. The chart below is a summary of the views of 10,000 economists from the English-speaking world collected and analysed by Armin Falk and Peter Andre (no, not that Peter Andre).

Economists’ views on what kind of economic research should be done

Source: Falk and Andre (2021)

The first thing to note is that in almost all respects there is practically a 50/50 split amongst opinions. Theoretical research or applied research, basic research or policy relevance, specialised or not. There is wide disagreement on these subjects. The only areas where I can find solid majorities are in favour of more multidisciplinary research and riskier, more provocative research.

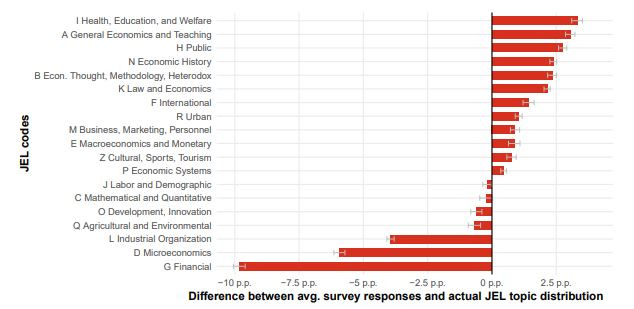

Yet, what happens in practice seems to be mostly the opposite. The chart below shows the difference between what economists think should be researched and the amount of research published in different fields. Negative bars indicate fields where a lot more research is produced than economists think necessary and positive bars indicate fields that are underresearched. Note that finance and microeconomics top the list of overresearched fields. No wonder, since this research is often relevant to businesses and thus easier to finance. Plus economists who want to have a career in the private sector better produce research that is relevant to potential future employers, whether this is necessary or not. Meanwhile, areas that naturally require an interdisciplinary approach like health and education economics, economics and the law, or public economics remain woefully underrepresented in published research. In the end, I think this is very much a reflection of incentives. Economists go where the money and career opportunities are and they are certainly not in public economics but in finance. And this is the general problem with today’s academia. It has become so dependent on funding that the output it produces becomes increasingly irrelevant to the really important questions of today – at least in the social sciences.

Should vs. is in economic research fields

Source: Falk and Andre (2021)