There is no law of gravity in finance

One of the things we have to be aware of is that there is no law of gravity in finance. Yes, there are some variables that should be mean-reverting. The classic example are corporate profit margins. When profit margins are high, the industry may be disrupted by new entrants who are willing to provide the same service or product at a lower cost and with lower margins, hence driving profit margins lower. When profit margins are low, some businesses will not be able to survive and leave the market, providing growth opportunities and less competition to the survivors. In a less competitive environment, profit margins can increase again.

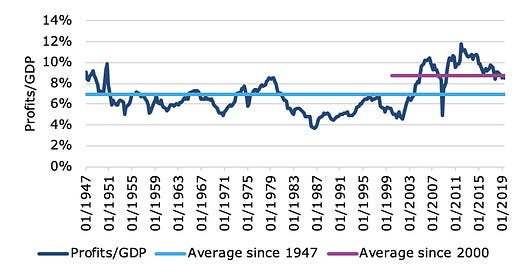

Here is a chart of US corporate profit margins over time. They are clearly mean-reverting in the long run, but as you can see the time it takes to get back to the long-term average varies dramatically. Profit margins have remained well above average for about a decade now without declining back to their long-term average. Instead, they have only declined to their average since 2000.

US Corporate profit as share of GDP

Source: St. Louis Fed.

It won’t help you to know that the average time for profit margins to revert to their long-term mean is 7 quarters from a peak and 19 quarters from a trough because, as the table below shows, the dispersion around these means is huge.

Time to revert to the mean for profit margins

Source: Klement on Investing.

Unlike in physics, there is no law in finance that says that if profit margins are far away from the mean they have to revert that quickly.

I had to learn that the hard way myself when I stood in front of clients in late 2014 and told them that it is unlikely that the 10-year Swiss government bond yield will ever drop below zero for a long time. Three months later it dropped below zero and has stayed there ever since.

Back then, I used my “insight” into the low level of interest rates to conclude that the odds of further interest rate declines are very low while it is far more likely that we will see interest rates normalise in the future. How wrong I was – and continue to be. I could find lame excuses why I wasn’t really wrong (after all, I am an economist and we are really good at finding excuses for forecasts gone wrong) but the truth is, I was wrong in asserting that interest rates have to normalise.

And this brings me to the Fed Open Market Committee meeting (FOMC) and the interest rate decisions of the Fed and other central banks in the West. It is still common knowledge that interest rates are currently too low and that at some point in the future they will have to normalise (where normalise means an increase to some arbitrary level higher than the current one). But there is no gravitational force that pulls interest rates higher.

Instead, as I have pointed out in this post, central banks are political institutions and thus have a strong incentive not to hike interest rates too fast or too far. They are incentivised to err on the side of loose monetary policy unless there is runaway inflation at which point the public pressure to fight inflation is so high that the central bank can get away with hiking rates quickly and decisively. If a central banker tries to hike interest rates without such an imminent inflationary pressure, he will be vilified as William McChesney Martin had to learn in the 1950s – an episode that triggered the loose monetary policies of the Fed that eventually led to the high inflation of the 1970s.

Over the last four decades, since Alan Greenspan took the helm of the Fed, we have gone from the Greenspan Put to the Bernanke Put, to the Yellen Put and the Powell Put. Yet, the decision when to exercise the put has changed with every chairperson. Greenspan only triggered the put after the tech bubble burst in 2000 and a recession was underway. Bernanke had to fight a global recession and the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression, a development the Fed noticed too late, so it had to overshoot the target to rescue the market from a global meltdown. Yellen then started to calm markets down as soon as recession fears were discussed in the news while Powell two weeks ago acted before we even had recession fears discussed in the market. Of course, by now, panic has taken hold of the market and the Fed has essentially thrown everything and the kitchen sink at markets - though so far with no success, which shows to me that monetary policy has become impotent as I have suggested here.

However, let’s take a step back from the current chaos in markets and reflect on the bigger picture and the initial actions of Jerome Powell a mere two weeks ago. Two weeks ago the Fed exercised its put option in anticipation of recession fears, not in anticipation of recessions.

That is an extraordinary shift in the exercise of the put.

Once the current crisis has been digested, investors can look back at it and learn that they can effectively blackmail the Fed into cutting rates. Not only do you not have to worry about losses with your risky investments, the signal is that investors don’t even have to experience short-term mark-to-market losses anymore. The Fed and other central banks will bail you out before you even have to recognise book value losses in your quarterly earnings.

And, far more importantly, the actions of the Fed two weeks ago open the gates to the implementation of MMT. There is a growing consensus that monetary policy can no longer fight recessions and that we have to increasingly rely on fiscal policy measures (automatic stabilisers as well as discretionary actions by politicians) to stimulate an economy in recession. The recent Fed actions provide politicians with a clear signal that it is willing to uphold its part of the bargain and keep interest rates very low and ideally below zero for a long time to make it easier for politicians to run large budget deficits.

(If you are not up to speed with MMT, I have explained it in a series of posts here, here, here, and here).

The implications for investors could be profound. If interest rates are low for a very long time, stock market valuations will remain elevated and may not revert to any past mean. Similarly, growth companies that rely heavily on debt to finance future growth can continue to finance themselves at very low rates and outperform companies that run lower debt levels and are profitable without the use of excessive debt. In other words, high yield bonds and leveraged loans may incur much lower default rates than in the past and growth may continue to outperform value for years to come. Remember, there is no law that value has to outperform growth in the long run and there is no law that leveraged companies have to default on their debt more frequently than other companies. These are just odds and it seems to me that the Fed and other central banks are rigging the odds.