Should we fight the 1%?

The rise of populist uprisings from the Occupy movement to Extinction Rebellion and its impact on politics around the world has opened the eyes of many economists and investors to a topic that has long been neglected: Inequality.

The traditional approach to economics looks at growth as something that is universally positive. If GDP increases by 3% in any given year, economists implicitly assumed that everybody will be better off at the end of the year. Maybe not 3% better off, but more or less 3% better off. Similarly, if wage inflation is 2% in any given year, economists typically assumed that all wages rise more or less by 2%. But of course, that is not the case in reality. GDP growth of 3% may be equally distributed across the society, but it can also be highly unequally distributed, with much of the spoils going to owners of capital while poorer households benefitted little form the growth of the economy. Similarly, wage inflation can be evenly distributed or highly skewed towards high-skilled labour.

And of course, that is what happened over the last one to two decades: owners of capital and highly skilled employees benefitted disproportionately from the recovery after the financial crisis. And the result was higher income inequality as measured by the Gini coefficient or the share of income garnered by the top 1%. Thomas Piketty wants you to believe that this advantage of capitalists over workers is a permanent feature of society, but I disagree. First, there is plenty of historical evidence of periods when inequality-adjusted downwards. In a recent post, I have described the evidence collected by Paul Schmelzig indicates that the rate of return on capital declines at a faster rate than the rate of growth of the economy. And Walter Scheidel assembles all the incidences since the Roman Empire when inequality declined rapidly. Unfortunately, he also comes to the conclusion that in order to reduce inequality permanently you need either a war, a pandemic (a real one like the black death, not Covid-19), a revolution or system collapse, which is a rather bleak view of history. To balance it out, I suggest you read Paul Schmelzig’s account in conjunction with Walter Scheidel’s so you don’t get tempted to cut your wrist.

Be that as it may, inequality as a subject of research has gained a lot of traction in economics but I fear, economists may be missing the forest for the trees once more. Naturally, economists tend to look at inequality from an income or wealth perspective and use measures such as the Gini coefficient as an indication of how unequal a society is.

But this approach leads to a conundrum. It is gospel amongst leftist politicians and economists that income inequality is bad for society and in extreme cases leads to riots and civil uprisings. Yet, the Godfather of civil war studies, Paul Collier, does not find a statistically significant influence of income inequality on the outbreak of civil wars. However, civil wars in countries with high income inequality tend to last longer, which is simply a reflection of the fact that in a highly unequal country, there is more to lose for the losers and more to gain for the winners. However, there is some evidence that income inequality can explain the likelihood of civil strife indirectly.

As usual, it boils down to the fact that humans are social animals. And inequality is not only vertical inequality (i.e. differences between different social classes or income levels) but also horizontal inequality. Horizontal inequality is experienced when people who are of the same social class or have similar incomes experience different chances to advance in life. This can be due to outright discrimination based on race, religion or other social markers, or it can be due to differences in health outcomes (e.g. some people in the US used to have employer-sponsored health insurance while others were excluded for pre-existing conditions), in personal safety (some neighbourhoods or towns may not be policed as well as others), environmental degradation (it’s no fun living next to a toxic waste dump), etc.

Take two families with the same income and the same wealth and put them into these different environments and they will think life is not fair and the life satisfaction of the family with the worse personal safety will be lower than the life satisfaction of the other. Economists will either tell you that this is just a random error term they are experiencing or that the family living in an unsafe neighbourhood could simply move to a safer neighbourhood. But as we know, it isn’t that easy. People cannot just pack up and move somewhere else, especially if they have family members who need care or go to school etc. Geographical mobility is remarkably low. If it were not, we would have seen far more people from Spain and Greece move to the UK and Germany during the Eurozone Debt Crisis than actually did. And we would have far more migrants and refugees on our borders than we have at the moment…

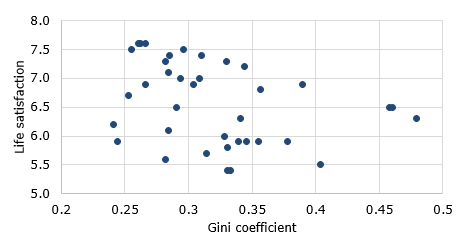

Using OECD data for 37 countries the chart below shows the relationship between income inequality (measured by the Gini coefficient) and average life satisfaction (given as the average response to a self-evaluation on a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being perfectly happy and satisfied). If you squint your eyes, you may be able to see a small negative effect (i.e. higher income inequality leads to somewhat lower life satisfaction). But this relationship is rather weak.

Little connection between income inequality and life satisfaction

Source: OECD.

On the other hand, there is a relatively strong link between life satisfaction and a Horizontal Inequality Score that I have calculated based on the numbers presented in the OECD’s Better Life Index components. The Better Life Index measures inequality in 24 variables, only two of which are related to income inequality. The others are all horizontal inequality measures. For each of the 22 horizontal measures, I gave a country 1 point if it is in the bottom third of the peer group, 2 points if it is in the middle and 3 points if it is in the top third. Then I grouped the 22 variables into eight functional groups similar to the OECD approach (functional groups are housing equality, educational equality, health equality, etc.). For each functional group, I averaged the score of each country and then added up all the scores. This means that each country gets a horizontal inequality score between 8 and 24 points, with higher scores implying lower inequality.

The chart below shows that the link between life satisfaction and Horizontal Inequality Scores is very strong with a correlation of 0.77.

Countries with less horizontal inequality (Higher Horizontal Inequality Score) have higher life satisfaction

Source: OECD.

The funny thing is that income inequality is linked to horizontal inequality, mostly because higher income allows you to buy a bigger house, better health insurance and send your children to better schools. The correlation between the Gini coefficient and horizontal inequality is relatively high at -0.54.

Correlation between income inequality and horizontal inequality

Source: OECD.

But while there is a link between income inequality and horizontal inequality, this link gets watered down by other influences when its impact on life satisfaction, civil uprisings or riots are measured.

What we learn from that is that the current efforts to rein in the top 1% are largely misguided. High income inequality isn’t the real problem. It is just an easy scapegoat. What drives politics and life satisfaction is horizontal inequality. Fighting income inequality is unlikely to provide relief in the perceived inequality of the daily lives of the people who demonstrate against inequality and the top 1%. And implementing redistributive policy measures as promoted by populist politicians on the left side of the aisle is unlikely to be an effective means to help the people who suffer the most today.

Instead, what is needed is a reduction of horizontal inequality by guaranteeing good healthcare for everyone, a safe environment to live in through better crime prevention, a cleaner environment, and more green spaces, better public schools and universities and a better community through increased social engagement. Ironically, I think both people on the left and the right of the political spectrum can agree on these goals. So why do we keep ourselves busy with polarised debates about taxes and the rich?