Assume you have the privilege to coach an NBA basketball team. In the first game, you score a narrow win over your opponent. Will you change your line-up for the next match? Now assume that the next match ends by the same narrow margin as the first game, but this time you lose by that margin. What are you going to do for the third match?

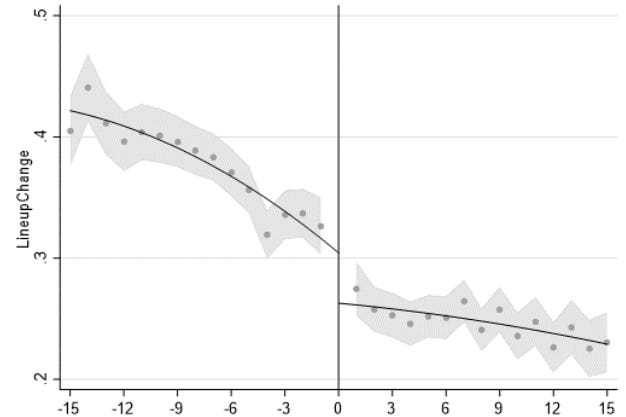

If you are a normal basketball coach, you are about 4% more likely to change the line-up of your team after a narrow loss than after a narrow win. This is the result of a study by Pascal Meier and his colleagues of coaches in the NBA, the WNBA, the NFL and NCAA basketball. The chart below shows the discontinuity in probability to change the line-up of NBA teams after a narrow win vs. a narrow loss.

Coaches are more likely to change line-ups after a narrow loss than a narrow win

Source: Meier et al. (2023)

Does that make sense? Probably not because narrow wins and losses are most likely determined by random factors that are outside the control of the coach. Yet, when faced with losses, we feel the urge to do something, anything really, to change the situation. After a narrow win, we are happy to rest on our laurels and do nothing, thinking that “you never change a winning team”.

If you think about it, that is also what happens in the investment world. So many analysts and economists have a streak of good luck in their forecasts (remember there are only two kinds of forecasts, lucky and wrong) and tend to continue to do the same thing until they experience a large error and have to go over the books to check what they missed. Probably, they missed something a long time ago, but they simply didn’t care because their forecasts were still working.

Similarly, fund managers tend to have a prescribed investment process and as long as their portfolios outperform the benchmark, they feel little need to tinker with the process. But let the portfolio underperform for a little while and they start questioning every detail of their investment process in an effort to turn their performance around.

This is why I emphasise that post-mortems or after-action-reviews should be performed at regular intervals or ideally after each major investment decision. Instead, what tends to happen is that people perform a post-mortem only once things have gone wrong. Just think of the investigation into the oversight of the San Francisco Fed over SVB Bank in California. The risk of omitting post-mortems after a successful investment is that you let the seed of future failures grow undetected until it is too late. And as the case of the San Francisco Fed and SVB shows, that failure can have massive ramifications.

Reminds me a lot of Deming’s funnel experiment. If you don’t know it, pick up a copy of Out of the Crisis.

This is so true and should be self-evident; but unfortunately is often overlooked - whether in sports, finance, project management, health, life.

On the other hand, over-reacting to (slightly) bad news is often as bad as ignoring the need for after-action-reviews during good times.