One of the most-read finance books of all time is Jeremy Siegel’s ‘Stocks for the Long Run’. However, in my view, this is also one of the most misunderstood books of all time because it promotes an unrealistically positive view of equities as this perfect long-term investment that can never fail if you only hold on to them long enough. Don’t get me wrong, I am a big fan of equities and think long-term investors should hold a lot more equities in their portfolio than most do (see here for an interesting view on retirement portfolios), but we are not doing us and our clients a favour if we claim that equities have little to no risk in the long run. This is why I am so grateful to Edward McQuarrie for setting the record straight in a brilliant article that contains so many important insights, that I will write about it in a three-part series over the next couple of Wednesdays. In this first part, I will focus on the absolute returns of equities in the long run.

In his article, which I recommend all of you read in full, Professor McQuarrie corrects the data that Jeremey Siegel used in his book in the following ways (and I am quoting directly from his paper here):

“Includes securities trading outside of New York, in Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and southern and western cities. The new record covers three to five times more stocks and five to ten times more bonds.

The expanded coverage captures more failures, reducing survivorship bias. Outside of New York, banks failed, turnpikes succumbed to canals, canals lost to railroads, and new railroads fell on hard times and never paid a dividend. States defaulted in the Panic of 1837. Corporate bonds were downgraded or defaulted.

Includes federal, municipal, and corporate bonds, and large numbers of each, as opposed to the one bond used each year by Siegel prior to 1862. The new bond record observes price changes, where Siegel had to infer price change from successive yields.

Calculates capitalization-weighted total return for stocks. The old record was either price-weighted or equal-weighted and lacked information on dividends.”

Based on this expanded data for the US as well as international markets, we can now look at the risks of equity investments in the long run. Is it really true that if one holds on to equities for long enough one is certain to make a profit? The answer is a resounding: It depends.

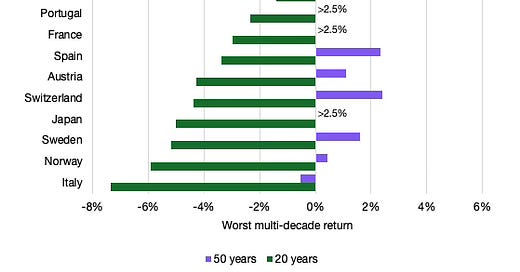

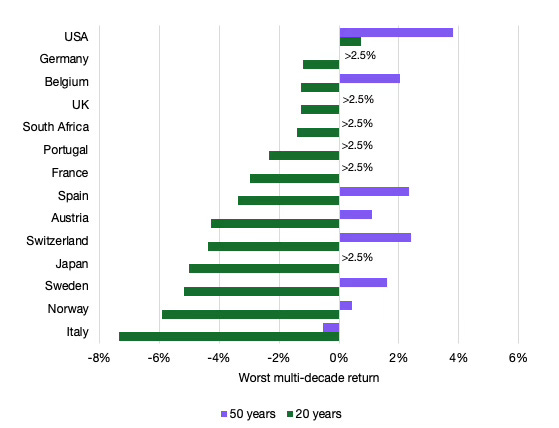

It depends on what you consider to be the long-term. The chart below shows the worst possible return over 20- and 50-year investment horizons for a series of international equity markets.

Worst returns over 20- and 50-year holding periods for equities

Source: McQuarrie (2023)

I make several observations:

If one thinks about the long term as 50 years or more (which is the case for pension funds, endowments, or sovereign wealth funds), then, yes, one is almost certain to make money with stocks. However, note the case of Italy which saw its equity market decline by 0.54% per year between 1961 and 2011 for a 50-year total return of -23.7%.

Over investment horizons of 20 years (which is a long-term investment for personal investors) the worst-case scenario has been significant destruction of wealth for every market except the US. The average worst return over 20 years is -3.2% per year, leading to a 20-year total return of -47.8%. Imagine holding on to equities for 20 years and still being left with half the money you started with – and that is before inflation…

The US market is the only one without a negative absolute return over any 20-year period, but don’t take this as an endorsement of US stocks. In the past 150 years, the US has not experienced major destruction from wars on its home soil, had no hyperinflation, no civil war, and was one of the very few countries that never defaulted on its government debt. Any of these major crises can kill the equity market for decades and while I don’t expect any of these things to happen in the next couple of decades they are still possible. Similarly, and far more likely than any of these major disasters, economic mismanagement can lead to a permanent decline in a country’s equity market. Remember that Argentina was one of the wealthiest countries in the world in 1900. And look at the Italian stock market and its long-term track record above.

Because you never know which country or region is going to be the star performer in the future and which one is going to be a dud, international diversification is key to successful equity investing in the long run. This way, you mitigate the impact of any negative outcome like the ones summarized above.

Yes, equities are a great investment in the long run, but they are not without risk and far from being a sure gain. This is particularly true when one looks at the relative performance of stocks vs. bonds as I will do next Wednesday.

One can conclude several things from that observations A) there is a huge component of luck in long term wealth management B) US economy is an unnatural outliner that is C) ripe for a "regression to the mean" .

I've written this piece about exponential growth of technical progress and its natural limits, but that is highly interwoven with economic growth, especially with US economy of the last decades:

https://theafh.substack.com/p/the-last-day-on-the-lake

and man, does this data look even worse if you go back 100 years. Germany, and I suppose Japan and Italy all went to zero.

One is reminded of what Tom McClellan's dad said, ""Everyone times the market. Some people buy when they have money, and sell when they need money, while others use methods that are more sophisticated."

And indeed, I do think it is a matter of buy-and-hold vs getting the hell out of Dodge while you can. It has been calculated that one made decent money (CAGR >7%) in post-bubble Japan if one sold the Nikkei whenever it went below its 200-day moving average, then using that cash to buy Japanese treasuries. (Wash and repeat).

One the other hand, this approach would have been completely useless for an investor in Germany 1944...