In part 1 of this series, I established that stocks can have negative absolute returns over very long investment horizons such as 20 and even 50 years. In this second part of my series, I want to look at the results of Edward McQuarrie’s study for the relative return of equities vs. bonds.

We have seen that even in the worst-case scenario, stocks in most countries had small positive returns after 50 years or so – an investment horizon typically too long for private investors, but entirely normal for institutions. But just because equity investments have a slightly positive return in nominal terms doesn’t mean that they are a great investment. Even over the longest investment horizons, there is a significant likelihood that bonds will outperform stocks.

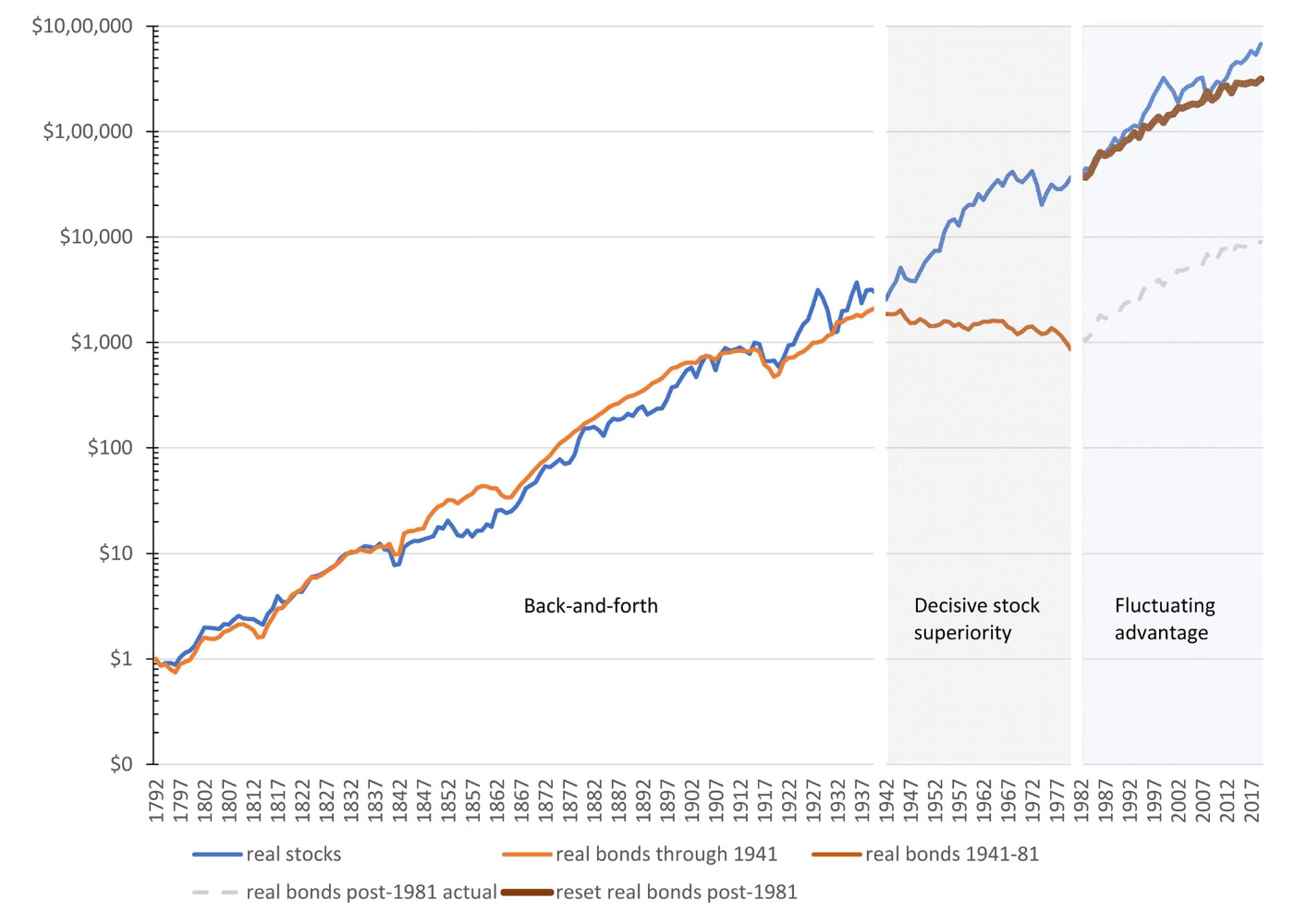

One of the most common charts in all of finance is the relative performance of stocks vs. bonds in the US in the long run. But as with all long-term historical data, there is a huge risk of survivorship bias. Stocks of companies that went under are often not included in the track record or, the track record of stocks and bonds is based on a very limited number of assets (in the case of Siegel’s ‘Stocks for the Long Run’ bond returns before 1837 were imputed from one bond only).

Edward McQuarrie went to great lengths to reduce this survivorship bias by adding more bonds and stocks from all marketplaces across the US to the data. And with one great chart, he dismantles the myth of stocks outperforming bonds in the long run. The chart below should definitely change your view on the relative performance of stocks vs. bonds in the long run.

Stocks vs. bonds in the long run

Source: McQuarrie (2023).

Outside the post-World-War years from 1941 to 1981 stocks in the US did not outperform bonds by any meaningful margin. Let me repeat that: Apart from the four decades to the 1980s, stocks did not systematically outperform bonds. Sometimes stocks outperformed bonds, sometimes bonds outperformed stocks.

If we take the entire track record back to 1792 we can see that while stocks are more likely than not to outperform bonds in the long run, even for investment horizons of 50 years, the chance of stocks beating bonds is just two in three. Invest for many decades and you still have a one in three chance that bonds will beat your stock portfolio.

Likelihood of stocks outperforming bonds in the US

Source: McQuarrie (2023)

But that is the US case and I have mentioned in the first part that US stock market returns are different from the rest of the world. Luckily, when it comes to the returns of stocks vs. bonds, the US is pr etty much middle of the pack when it comes to the worst possible outcome. Most countries show a significant underperformance of stocks vs. bonds in the worst case both over 20 and 50 years.

Worst relative returns over 20- and 50-year holding periods for equities vs. bonds

Source: McQuarrie (2023)

To be clear, I am not trying to convince readers to abandon stocks. As I keep telling everyone, equities are a great long-term investment and in the long run, they are likely to outperform most other asset classes and in particular bonds. The data bears that out with equities beating bonds in two out of three cases.

But I warn against looking at equities as a panacea. Equities can disappoint more often than many investors believe. These overly optimistic expectations about equity returns are what lead to disappointment and make investors turn their backs on stock markets for many years, often at the very moment, stocks start to outperform again (and any investor in UK or emerging market equities will likely nod along right now).

Given these results, one can conclude that even long-term investors should consider bonds in their portfolios as a means of diversification. But for bonds to act as a diversifier to equities, they need to have a low or negative correlation with equities. And in the third and final part of this series, I will look at the long-term trends for the correlation between stocks and bonds.

Matthew, Thanks for both Part 1 and Part 2. I've always heard that debt markets are bigger than stock markets. What I can find quickly shows Global Bond market cap at $133 Trillion, and Stocks market Cap (for 10 largest) at $89.5 Trillion.

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/04/ranked-the-largest-bond-markets-in-the-world/

https://www.visualcapitalist.com/the-worlds-10-largest-stock-markets/

And, clearly there's a lot of debt trading in REPO, CDRs, and other types of debt derivatives, that generally are only available to finance institutions and not to individuals.

Let's just posit that there's no "clear" evidence that stocks always outperform bonds, even on longer periods (horizons). Let's also posit that stocks and bonds are only two of many asset classes. What other (alternative) assets have comparable performance?

So what about DMS data they publish in Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Yearbook?

And The Rate of Return on Everything (2017) data?

https://imgur.com/a/ArnoAKR

They are not that long (since 1870/1900), but I don't see bonds being on par with equities in these.