Most people are vastly overconfident about their abilities, their knowledge, etc. Back in the days when I was working in private banking, I used to subject clients and advisers to a short overconfidence quiz to make them realise how overconfident they really are. If you want to, you can take the quiz yourself here.

Needless to say, hardly anyone showed an unbiased and realistic estimate of the uncertainty around their answers in that quiz.

However, overconfidence leads to all kinds of mistakes. In the investment world it can create excessive losses in all kinds of inventive ways (it never ceases to surprise me how inventive investors and their advisers are in finding new ways to lose money).

But overconfidence should also be an evolutionary disadvantage. If we think we can outrun a predator or fight it even though it is bigger and stronger than we are, chances are we won’t pass on our overconfident genes.

So, if overconfidence is a problem, evolutionary speaking, why are we still overconfident? This trait should have been eliminated by Mother Nature a long time ago.

This is where a paper by Dominic Johnson and James Fowler comes in. It was published in one of the most influential academic journals in the world, Nature, yet somehow it never made it into the public consciousness that is typically shaped by pop science books written by Malcolm Gladwell, Yuval Noah Harari, Jared Diamond, and the like.

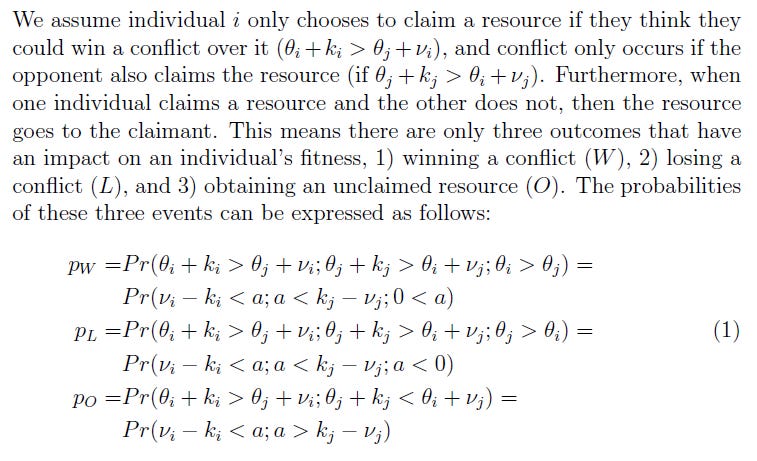

I guess that these authors had they considered reading this paper would probably have been – let’s say – ‘challenged’ since it contains a bit of maths. Here is how it starts with the most basic equation (1):

But if you make it through the paper, you learn quite a few interesting things.

First, you learn that whether evolution selects for overconfidence or rational/underconfident behaviour depends on the environment and the costs and benefits of being overconfident.

Think about it this way. In nature, every animal needs to find and secure resources to feed itself, mate and pass on its genes to the next generation.

Now assume you wander through the savannah and see a recently diseased antelope or the Stone Age equivalent to Scarlett Johansson. You can choose to claim the antelope/Scarlett and will do so if you can consume the resource before someone else gets to it or defend it against any challenge from a rival.

If you think you are not strong enough to defend your new possession against rival claims, you will retreat and look for another resource that is easier to defend, say a dead rabbit or the Stone Age equivalent of Rosie O’Donnell.

If you are overconfident, the risk is that you claim a resource that you will eventually lose if you get challenged by a stronger rival. But how likely is that and what are the costs to losing that resource? Turns out in most cases the likelihood of the Stone Age equivalent of Brad Pitt coming along to claim Scarlett Johansson is pretty small and if he does come along, you can put up a fuzz but eventually just retreat at relatively little cost. The benefits outweigh the costs by a lot.

On the other hand, if you are underconfident, you may not claim resources that you realistically could defend against a rival, and you will starve or not be able to mate and create offspring.

Hence, the larger the benefits relative to the potential costs, the better for you to be overconfident. And the larger the uncertainty around a potential resource, the more overconfident you should become because, in a highly uncertain environment, the risk of even meeting a rival that can take a resource away from you is potentially much smaller while the benefits could be much larger. A more uncertain environment naturally selects the most overconfident people who don’t care about the losses to them or their tribe.

But this is the typical setup in nature. We are constantly facing high uncertainty about both the costs and benefits of our actions but as a general rule, the benefits typically outweigh the potential costs (because in most instances we can walk away from a loss and try again another time).

Hence, evolution breeds for overconfidence. And the more uncertain the environment, the more it attracts supremely overconfident people because they are less sensitive to the potential risks and costs.

In a highly uncertain economy or a complex political and economic situation, we are more likely to vote for overconfident politicians who promise simple solutions (aka populists). Assets that are highly volatile or more complex and opaque are more likely to attract overconfident investors (aka young men). And when faced with uncertain and complex natural risks, we tend to flock around people who claim that it is all going to be fine (aka climate change deniers).

In that respect, the fact that it is high season for conspiracy theorists, populists and charlatans tells you more about how complex and uncertain our world has become than about the people who fall for them.

Evolutionary outcome for over- and underconfidence for different levels of costs and benefits

Source: Johnson and Fowler (2011). Note: left hand side (c) is a binomial model, right hand side (d) is a normally distributed model.

Interesting! A modern example could be an start up founder who overestimates its success chances. It's a high uncertainty situation with relatively larger potential benefits than costs, so overconfidence might turn out to be an advantage.

Thanks for this, Joachim. I clicked through to the overconfidence quiz, and it occurred to me that a clever participant might go for very wide spreads between min and max, paired with a confidence of, say 95%. Perhaps nature selects for market making skills!