Inflation is high and central banks are hiking interest rates, thus increasing mortgage rates and making houses less affordable. Clearly, the current bout of inflation has an immediate impact on the housing market. But what are the long-term implications? As it turns out, our experience of the current high inflation is likely to change our attitudes towards houses and mortgages forever.

Ulrike Malmendier has almost single-handedly (with apologies to Stefan Nagel who collaborated with her in many cases) created the field of lifetime experiences and how they influence economic decisions. Her note on how the Great Depression shaped the behaviour of people for the rest of their lives led to a complete rethink among many economists on how people make decisions.

But one doesn’t need a seminal event like the Great Depression to change behaviour. An extended period of high inflation will do just as well. In 2021, Ulrike Malmendier and Matthew Botsch demonstrated that the average inflation experienced during one’s lifetime influences the kind of mortgages people use to finance their homes. People who lived through the high inflation of the 1970s expected inflation to be higher in the future, even decades after the end of the high inflation period. And because they expected inflation to be higher, they preferred fixed-rate mortgages over adjustable-rate mortgages. If you expect inflation to rear its ugly head again, that means your mortgage rates are going to go up, so better fix them for as long as you can.

Here in the UK, mortgages were traditionally floating-rate mortgages. Before the housing market collapse in 2006-2008, more than 80% of all mortgages were floaters. In the aftermath of the housing crisis, banks were much less willing to sell these floating-rate mortgages and instead offered more fixed-rate mortgages. Today, according to the Bank of England, 85% of all UK mortgages are fixed with some 61% fixed for five years. And of newly issued mortgages, some 91% are fixed-rate mortgages.

This is probably where I have to explain to my foreign readers, particularly in the US, that the UK mortgage market has its idiosyncrasies. In most European countries the standard mortgage is a 10-year fixed rate mortgage and in the US, it is a 30-year fixed rate mortgage. Here in the UK, we wish, we had these options. As I have said, historically most mortgages were adjustable-rate and after the housing crisis, the best UK lenders could come up with are a choice of 2-year fixed or 5-year fixed mortgages. I don’t know why UK banks aren’t able to offer 10-year fixed-rate mortgages. It is one of those British eccentricities like quoting share prices in Pence instead of Pounds Sterling. It makes everybody’s life harder, but they keep on doing it because they have always done it this way…

But the UK experience is symptomatic for people who experience higher inflation throughout their lifetime. The higher the experienced inflation, the more likely people are to take out a fixed-rate mortgage instead of an adjustable-rate mortgage. This has implications for monetary policy and the housing market. If a larger share of mortgages is fixed, it takes longer for higher interest takes by central banks to cool a booming housing market or to cool an overheating economy. The lag between the central bank hiking interest rates and these higher interest rates influencing the real economy becomes longer and monetary policy becomes harder.

But there is also good news. If you experience higher inflation in your lifetime, you are more likely to seek to protect yourself against higher inflation. And what better way to do that than to own your house instead of renting it? In another paper, Ulrike Malmendier together with Alexandra Wellsjo showed that countries with lower historical inflation have lower homeownership rates. I have always been fascinated by the differences in homeownership rates between countries. In Germany and Austria, homeownership rates are extremely low at some 40% to 50%. Meanwhile, in the UK and the US, homeownership rates are between 60% and 70%.

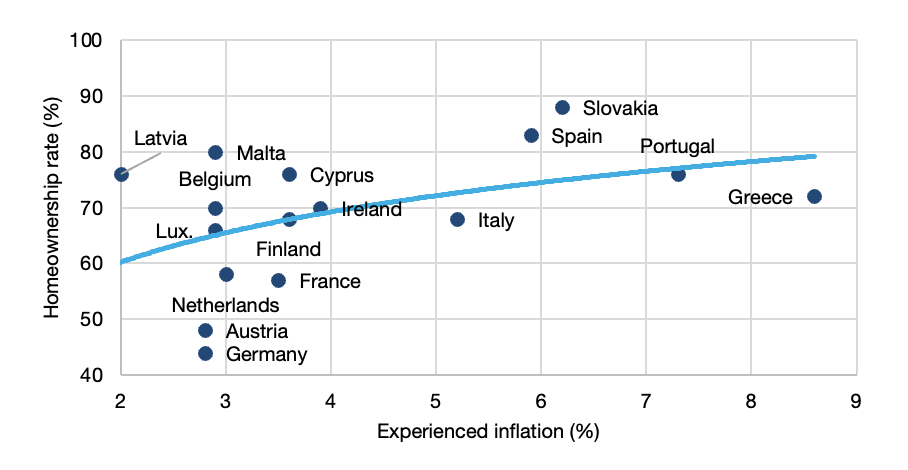

There are many reasons for these cultural differences but the inflationary environment in different countries is certainly one of them. Immigrants in the US who come from countries with high inflation are more likely to own their homes in the US than immigrants who come from countries with low inflation. And the chart below shows that the average experienced inflation in 20 European countries is linked to the homeownership rates in these countries. A one-percentage-point increase in the lifetime inflation experience of a person increases homeownership rates by some 19 percentage points. The current inflationary environment is likely to increase lifetime inflation averages by less than 0.1 percentage points, but if inflation hovers at high levels for longer or settles to a new normal of around 3% instead of 2%, the impact on homeownership rates could be large. And that would provide a large investment opportunity in housebuilding stocks in Europe because somebody has to provide the supply for this increasing demand.

Link between lifetime inflation experience and homeownership rates

Source: Malmendier and Wellsjo (2020)

Another reason for a higher percentage of home-ownership is the lack of a good pensionsystem. For example, the Netherlands have a high share of their private wealth invested in pensionfund schemes (at the moment Euro 1.500 billion). Whereas people in countries like Italy or Spain have to invest in a home to create wealth for their own pension.

Nicely written.

Not sure if European housebuilders are going to be a winner - declining and aging population, plus very restrictive building regulations in some places might spoil the fun.

In the UK many of the generation born 1910s didn't trust banks, investments or gilts. I can remember old people with their life savings at home in cash. This generation has died but no doubt we'll have similar quirks for future cohorts who've lived through 2008-2010 and Covid. What will our quirks be?