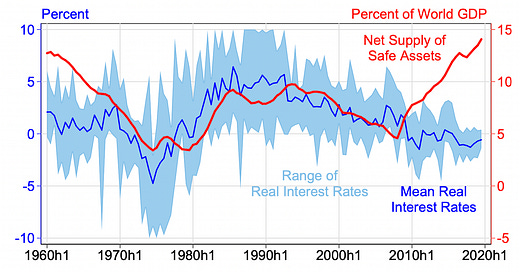

As another part of my quest to convince people that monetarist theories of inflation and interest rates are dead, let me present you with the following chart that shows the net supply of safe assets in developed countries and the real interest rate in these countries.

Net supply of safe assets and real interest rates

Source: Ferreira and Shousha (2021)

From the 1960s to the financial crisis the net supply of safe assets (i.e. government bonds) was closely linked to the real interest rates around the world. Declining supply meant that prices for safe assets had to increase, which in turn pushed real rates lower. Increase supply meant prices had to fall and real rates rose. That is the basics of supply and demand when it comes to government bonds. And that was at the heart of the argument back in 2009 and again in 2021 that all that deficit spending and should lead to higher inflation and higher interest rates, which finally will translate into higher risk premia for government bonds and thus higher real rates.

…except it never happened.

I have explained here how the world has changed since the financial crisis and how the introduction of zero interest rates has been not just a quantitative change but a qualitative one. And the chart above underscores how the world has become a very different place over the last decade.

But the dynamics of supply and demand don’t just disappear. They tend to work all the time in a free market. And if the rapidly rising supply of safe assets hasn’t increased real interest rates, there should be other drivers that have overwhelmed the supply effect and pushed real interest rates lower over the last decade. Personally, I think a lot of it has to do with the changed behaviour of banks, businesses, and investors in a zero interest rate environment, but two researchers from the Federal Reserve have tested the influence of other macroeconomic developments on real interest rates and compared them to the influence of the rise in the supply of government bonds. The researchers used three potential drivers of real interest rates besides the supply of safe assets:

Productivity: We have witnessed a decline in productivity growth over the last decades. Note that this channel is linked with the overall level of interest rates. If productivity growth declines, businesses have less of an incentive to invest, which in turn means that productivity growth in the future declines even more. To counteract this lack of investments, central banks have to lower interest rates (eventually ending up at zero interest rates). But ironically, if interest rates come close to zero, households have to save more of their income in order to make up for the lost interest income of their savings. The result is a savings glut where households consume less and save more thus reducing the incentive for businesses to invest (because if there is not enough growth from end-customer demand, why bother investing?) and productivity falls even more. And because consumers don’t earn any interest income in safe assets like government bonds, they don’t invest their savings into these safe assets but rather into stocks or real estate. The end effect is that while savings increase, the demand for safe assets doesn’t (or not by much), thus pushing interest rates even lower. I know this is exactly the opposite of what economic textbooks say should happen, but did I mention that a zero interest rate world is qualitatively different?

Aging demographics: As the share of working-age people declines in Western countries, the demand for safe assets as part of their household savings should decline as well. Furthermore, a declining supply of labour reduces the marginal productivity of capital, thus reducing the real rate of interest.

Convenience yield: This is the difference between high-grade corporate bonds and government bonds. The relative size of the convenience yield vs. the real yield of government bonds is what determines the demand for government bonds and corporate bonds. If the convenience yield is high relative to the real yield of government bonds, investors will switch out of government bonds and into corporate bonds.

The chart below shows how the real rate of interest on government bonds in different countries has been influenced by these four factors as well as international spillovers from other countries. The maroon bars are the influence of the supply of safe assets, and it indeed has created substantial upward pressure on real interest rates over the last decade. But declining productivity growth, an aging population, and global spillovers have all counteracted the upward pressure from the rising supply of safe assets.

Drivers of real interest rates over time

Source: Ferreira and Shousha (2021)

Interestingly, a decomposition of the variance of real interest rates shows that the net supply of safe assets and the change in productivity growth each explain about one-third of the variation in real interest rates. The convenience yield explains another 15% to 20% of changes in real interest rates. Meanwhile, demographics explain only about 5% of the change in real interest rate. Did I mention that I tend to ignore demographic projections because they are utterly useless and too small to matter in practice?

But what this research really shows is that if we ever enter a world where governments reduce their deficits and thus reduce the supply of government bonds (in my view, you shouldn’t hold your breath on this one, but let’s be optimistic) the impact on real interest rates would be to push them lower, thus creating even more of an incentive to switch out of government bonds and into higher-yielding assets like stocks.

If a government issues debt and a branch of the government purchases that debt, makes the interest payments back to the government, and ultimately retires or rolls over the old debt with new debt, is there any debt created? Aren't we just playing a new version of monopoly? Has the elusive perpetual motion machine finally been invented?

With a dislocation like the one you plot, is it not right to conclude that the only way out of the funk is to allow a crash in speculative assets or grossly devalue the currency? Investors absorbed the mid-2010s expansion without inflation on the expectation that some variation of the former would eventually prevail; the policy response to COVID (at least in the US) led many people to consider that they had insignificantly hedged against the possibility of massive inflation. If the above narrative is true....where do we go from here?