Yesterday, I wrote about a study that tried to measure how stock market returns react to increases in geopolitical risk (in particular war risk). I concluded that stock market investors seem constantly on the lookout for potential disasters and react negatively the moment there is an increase in the threat level. If this is true, then there should also be a long-term risk premium associated with the risk of rare disasters like wars.

Behavioural finance guru David Hirshleifer teamed up with two other researchers to analyse seven million articles in the New York Times published over the last 160 years and measure how discussions of war have influenced equity risk premia. It is thus a close relative of the research I discussed yesterday, except that in the case of this study, they focus on changes in equity excess returns for investment horizons of up to three years.

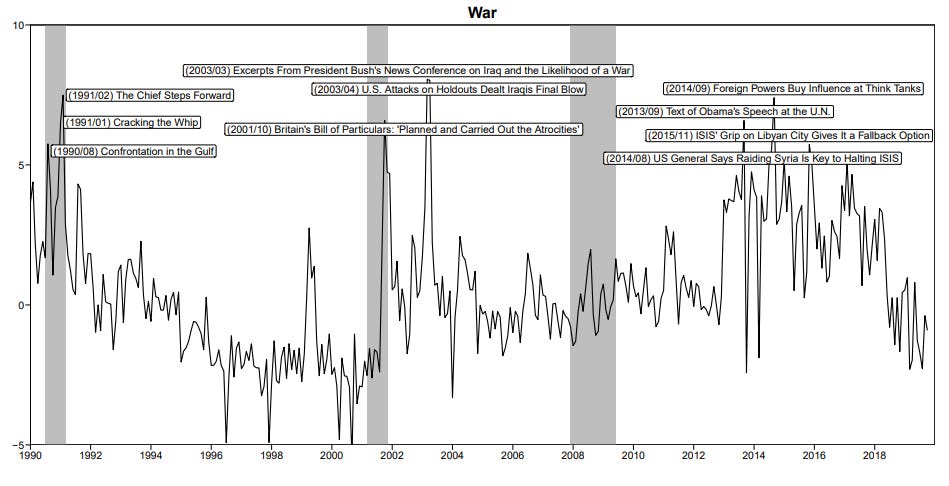

Ten articles that have contributed to the discourse on war threats since 1990

Source: Hirshleifer et al. (2024)

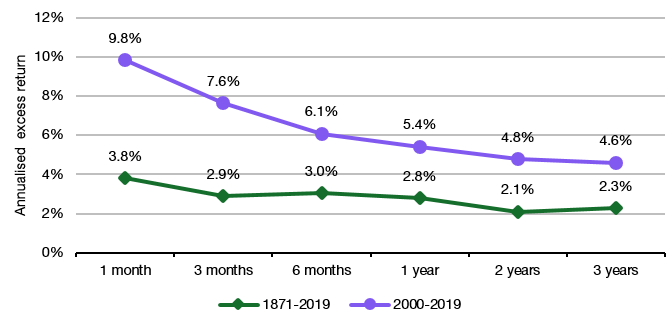

The main results for the US market shown below show two things. First, the highest excess return is available in the month after war threats have increased. This is the recovery after a sentiment shock from rising geopolitical risks that I discussed yesterday.

Second, the excess return of US stocks over Treasury Bills remains elevated for the next three years and it seems to have increased since 2000 compared to the average since 1871.

US equity excess returns in the years after an increase in war risks

Source: Hirshleifer et al. (2024)

The authors explain this effect using the theory that stock market excess returns can be explained with markets pricing rare disaster risks – a theory that I find rather unconvincing and that hasn’t very many empirical papers in its favour. Wars have become rarer over time (at least major wars that impact the US) and that implies that excess returns after an increase in war threats may have increased because investors are less prepared to take them into account and thus react more negatively to rising risks (thus giving way to even higher excess returns once markets recover). Whether this theory is the correct explanation is up for debate, but what is clear is that buying when war risks increase is a good strategy, even for longer-term investors.

The Dow had dropped in the spring of 1962, bottomed in the summer and slowly rose during the fall. It continued to rise during the Cuban Missile Crisis (November, 1962).

The moral, I suppose, is that the rumors of war must be of a war that you think you can outlive.