Maybe it is because I am German, but I am fascinated by the decline in productivity growth in Europe and North America. In the past, I have written about the decline in research productivity and the reduced capital investment in workers. Now, a new study has tried to assess the relative importance of these and other factors in a range of countries.

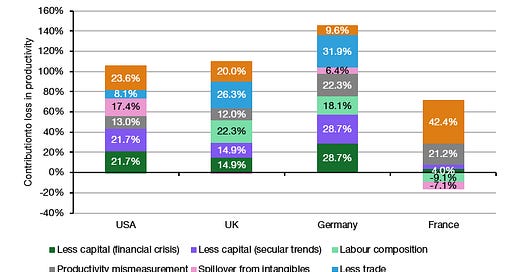

The research of Ian Goldin and his colleagues from Oxford University is a veritable tour de force to assessing what could drive labour productivity. Every bit of detail is examined carefully and teased apart from the other potential influences. In the end, they often can explain more than 100% of the observed drop in labour productivity between 2005 and 2017, which means that there may be some other factors that have increased productivity somewhat. My chart shows the results for the US, the UK, Germany, and France in comparison.

Contribution to labour productivity decline 2005-2017

Source: Goldin et al. (2024)

A couple of things stand out:

The loss of capital investments in productivity-enhancing technologies as well as worker education and training is the dominant driver in most countries. It explains c.43% of the productivity decline in the US, c.30% in the UK and a large 57.4% in Germany. They estimate that about half of this decline is due to the lack of access to capital and the lack of investment during and after the financial crisis and the other half is driven by secular trends.

The changing labour composition from an ageing population was a major driving force in the UK and Germany.

Fewer benefits from international trade accounted for about a quarter of the productivity decline in the UK and close to a third in Germany. This is a result of these countries either having less access to the most productive technologies or being replaced by other countries in global value chains and thus losing the incentive to invest.

Finally, there is about 10% to 20% of the productivity decline that is likely due to measurement errors and the inherent difficulties in determining what constitutes productivity growth.

Which brings me to the last component, labelled ‘Misallocation of resources’ in the chart.

This is the second most important driver for productivity decline in the US and the most important one in France. But even in the UK, it explains about 20% of the observed productivity decline. This sounds like businesses are not putting the right people to work in the right places, but it is more complicated than that. In effect, this is a combination of several factors, all of which reduce competition and introduce market friction.

First, there is the misallocation of human resources. This is the result of some industries paying more than others and people going where they can make the most money with their talents, even if these industries have small productivity growth. To put it bluntly, this reflects that people prefer to work in finance, law, and consulting (three sectors with low productivity growth) rather than engineering and technology.

Second, there is the trend toward less competitive markets and large businesses building moats around their products and services and stifling competition. This is the most important driver for the misallocation of capital in the US and UK where the largest companies have managed to remove a lot of their competition and now can earn huge profits without the need to innovate or increase productivity. The US tech space is no longer a competitive market because if it were, companies like Microsoft, Meta, or Apple couldn’t keep the operating margins they have right now – and indeed had for more than a decade.

And finally, the misallocation of capital results from the persistent decline in bankruptcies and creative destruction. I disagree with Austrian economics on almost everything, but there is a lot of truth in the power of creative destruction. Yet, the rate of firm exits and startup creation alike has declined in the US and most developed countries. Where zombie companies are allowed to continue operating, many resources are wasted, and employees remain in jobs with low productivity growth. And where there are fewer startups, there are fewer highly productive new jobs created.

Americans like to emphasise how efficient their economy is. Yet, it is precisely their economy that is more wasteful and less efficient than most. Among the countries examined in this research, only France wastes more resources through misallocation.

First of all thanks for your newsletter. Top!

Regarding productivity I often think about the missed opportunities, considering all the tech driven productivity tools that have been made available over the years. Excel, Word, email, video conferencing, the list goes on. A lot of this goes to waste because we have added unnecessary and wasteful activities and lots of extra red tape. Imagine doing what we did 50 years ago with the help of today’s tools …. What a productivity explosion …

The tremendous amount of Western resources going into renewables is both raising the cost of energy and siphoning away resources from productive uses to the unproductive. If one is convinced of the climate crisis thesis, a more rational approach would be to design a modular nuclear plant that can dispatched across a range of its output. It would be mass produced off-site, with all the regulatory/safety variables accounted for.