The more you know a stock the worse your performance gets

I use to joke that I can tell which country an investor lives in and which industry she works in just by looking at her portfolio. It is a natural tendency for all of us to invest predominantly in companies active in our home country or the industry we work in. Unfortunately, this tendency can lead to portfolios that are not diversified enough. If you are predominantly invested in energy or mining stocks, you might on the one hand miss the returns achieved in technology stocks in recent years or suffer more than other investors if there is a major decline in commodity prices like the one we have seen at the beginning of this year in the wake of the Coronavirus outbreak in China.

Of course, one might compensate for this lack of diversification by knowing more about a company, industry or country than the average investor. Didn’t Andrew Carnegie say the way to become rich is to put all your eggs in one basket and then watch that basket? However, the evidence is mounting that your performance becomes worse, the more you watch that basket.

Ellapulli Vasudevan looked at the portfolios of 308,000 Finnish investors between 1995 and 2014 as well as 76,000 US investors between 1991 and 1996. He found that many investors tended to buy and sell the same stock over and over again. About 40% of investors sold all of their holdings in a stock just to buy it again at a later time. And 10% of investors engaged in at least 6 of such roundtrips.

It seems as if a significant portion of investors follow Carnegie’s maxim of having just a few eggs in their basket and then watch that basket, trying to reduce short-term losses by selling some of the eggs temporarily and then buying them back when the risks have subsided. As I have written before, these investors are more likely to sell their stocks when they are sitting on a gain than when they are sitting on a loss, but what is novel about Vasudevan’s research is that he shows what happens once investors have sold the stock.

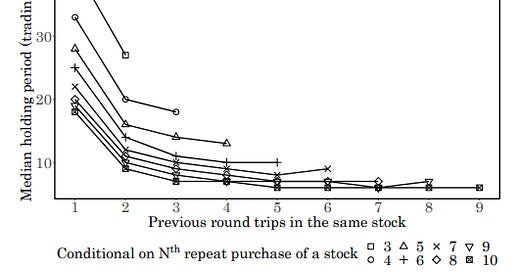

It is most likely for investors to sell a stock when they have made a profit but experienced some recent setbacks in the stock. They have made good experiences but held the stock too long, so when they buy the stock back they tend to watch the basket of eggs even more closely. This way, it seems, they are trying to avoid the lost return from holding the stock for too long. But what they effectively do is teach themselves to become short-term traders. Every time they buy the same stock again, the average holding period declines by about 11%.

Median holding period of stocks in every roundtrip

Source: Vasudevan (2020).

Unfortunately, by watching their stocks more closely, they are more likely to react to short-term noise. As they try to anticipate the next correction, the returns of their stocks become smaller and smaller. The chart below shows the annualised alpha relative to the market for every roundtrip. Because every roundtrip becomes shorter and shorter, one would naturally expect the alpha to become smaller, but the annualisation guarantees that this effect is compensated for. And yet, every time they buy the same stock again, the performance relative to the market declines.

Annualised alpha for successive roundtrips in a stock

Source: Vasudevan (2020). Note: “Nonfinal” indicates roundtrips in stocks that will be bought back at a later time, while “Final” indicates roundtrips of stocks that are never bought by the same investor again.

What makes the analysis above so interesting is that it also indicates when this process of buying and selling the same stock stops. At some point, the performance of a roundtrip will likely be very poor. This might be because of a misjudgment by the investor, but more likely happens just by chance. After all, the more often you check your investments, the more you will see short-term noise and react to it. And when this short-term behaviour goes all wrong, one can experience significant losses. At this point, investors apparently become fed up with that stock and stop buying it. The average performance of the last roundtrip tends to not only be very poor but the damage gets worse the more roundtrips the investor has made.

By putting all the eggs in the same basket and then watching that basket closely, the investor has accidentally broken one egg, after which that egg gets discarded and the investor focuses on the remaining eggs. Until one of these breaks, etc.