The Virtuous Investor: Rule 14

Don’t let your virtues slip – just because you are doing good does not mean you can get away with some vices

This post is part of a series on The Virtuous Investor. For an overview of the series and links to the other parts, click here.

“We must take very good heed that we despise not any vice as light, for no enemy overcometh oftener than he which is not set off.”

Erasmus of Rotterdam

We humans have an uncanny ability to cheat ourselves. As I have shown in another post there is a phenomenon called moral licensing that shows if we behave morally or virtuous in one domain, we might allow ourselves to behave immorally in another. After all, if we donate to a charity, we can’t be bad people even if we cheat at an exam, can we?

The funny thing is that this happens every day in financial advice. Professional financial advisers often face conflicts of interest when dealing with their clients. This is particularly true for financial advisers at brokerage firms in the United States, where they have to follow only the suitability rule and not live up to the fiduciary standard. The key difference, for those who don’t know, is that under the suitability rule an adviser must only check if a recommended product is suitable for the client, while under the fiduciary rule she must check that the recommended product is in the client’s best interest. Hence, under the suitability rule advisers can easily recommend products that provide them with the highest sales commission or fee income. This is the reason why financial advisers in many countries around the world now have to follow the fiduciary standard and put the client’s interests above their own.

The thing is that if advisers aren’t forced to put their clients’ interest above their own, they act selfishly and tend to recommend products that provide them with higher commission fees. Funny that.

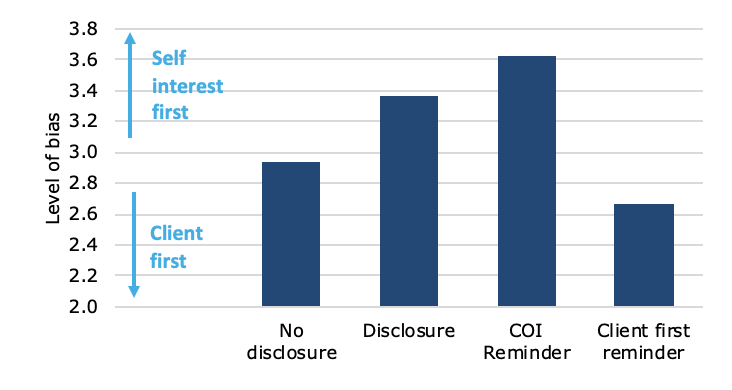

The chart below shows the result of an experimental study with 588 volunteers who were recruited to give financial advice to three imaginary clients. They could either recommend Fund A that did not pay commissions or Fund B that paid commissions. If there was no disclosure about the conflict of interest, advisers on average slightly favored Fund A but a substantial minority gave biased advice and recommended Fund B.

One popular remedy against biased advice is to force advisers to disclose conflicts of interest, but as the chart below shows, that just led to more biased and self-interested advice! This increasingly self-interested behavior has been predicted by several studies and can be understood as a form of moral licensing. After all, if I have to disclose my conflicts of interest then it’s the client’s fault if she does follow my advice. Also, if my client knows my advice is biased, I might need to exaggerate my bias so that after the clients discounts my bias I still end up where I used to be without disclosure. If that sounds cynical then be aware that studies have shown that advice becomes more biased the lower the cost of information gathering about biased advice becomes for clients. The more transparent the bias becomes to clients, the more biased the advisers seem to act.

Biased advice by non-expert advisers

Source: Sah (2019).

Another effect shown in the chart is that advisers become even more biased in their advice if they not only disclose their conflicts of interest but if they themselves are reminded of their conflicts of interest before they give advice (COI reminder in the chart above). This is meant to simulate a situation where the adviser is reminded by her boss or her company that selling Fund B is good for business. As the experiment shows, that is a sure-fire way to create biased advice that is not in the best interest of clients.

But bias does not always increase if we behave seemingly moral in one domain. If the advisers are reminded of their obligation to put clients first before giving advice, their bias declines afterward (Client first reminder in the chart above). Also, other studies have shown that more experienced advisers tend to give less biased advice. One driver for this phenomenon is that more experienced advisers seem to have learned that giving financial advice is a long-term activity. If you burn your clients with biased advice, they will not stay with you for a long time. Experienced advisors have learned to go for sustainable relationships and repeat business.

Conversely, for investors who are clients of financial services firms, this means that they should be on the lookout if they deal with an inexperienced adviser at a firm that does not have to follow the fiduciary standard.

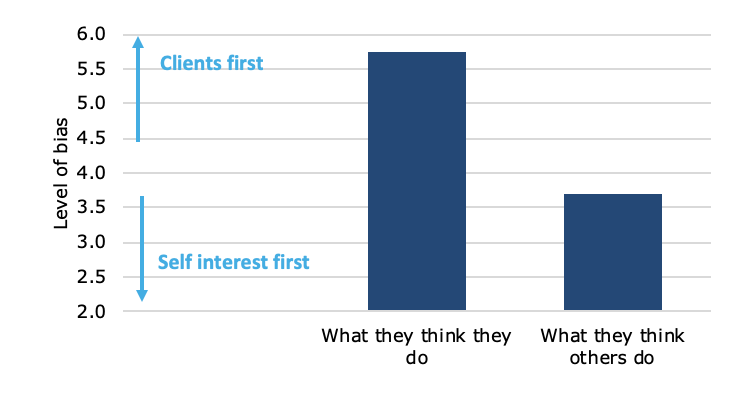

But when it comes to our own investments, we have to be aware that most of us aren’t experts and can bias our actions subconsciously. Take a look at the chart below which are the responses of financial professionals when asked about financial advice on Fund A and Fund B from the experiment above. The financial professionals were asked if their advice is biased and self-interested and if they think that the advice of their colleagues is self-interested. On average, the financial advisers thought that the advice they gave was not self-interested while they thought that their colleagues were giving biased advice.

It’s the classic experiment: Ask a group of people if they think they are above average drivers, and more than half will raise their hands. But that is statistically difficult. Only about 50% of the people can be above average.

If you want to be particularly poignant, you might want to ask a group of people to raise their hands if they think they are above-average lovers. Let me know the results if you do because I have never been able to muster the courage to do that in a room full of strangers.

In any case, we can’t all be unbiased while the average of all of us are biased. So, the virtuous investor needs to be aware that even if she follows all the rules of the virtuous investor, makes a plan, invests for the long run and ringfences speculative investments, etc. She might still easily fall prey to some of the mistakes I have described in the previous editions of this series. Always be on the lookout!

Financial professionals’ perception of bias in advice

Source: Sah (2019).