The Virtuous Investor: Rule 18

Stop worrying about trifling matters – Some things are just not worth the fight

This post is part of a series on The Virtuous Investor. For an overview of the series and links to the other parts, click here.

“In trifles and matters such as skillet not if all the world knew, we take some deliberation and advisement with ourselves.”

Erasmus of Rotterdam

The investment world is obsessed with the word optimise. We constantly try to optimise the portfolios we invest in, the withdrawal strategies for retirement, the taxes we pay etc. And that is a good thing. As advisers, our job is to help our clients make better decisions and get them the best possible outcome for their financial lives.

But in our efforts to optimise investments, we – that is professionals and private investors alike – go too far and start optimising the deck chairs on the Titanic. We get bogged down in tiny details of our investment decisions while forgetting the big picture. In fact, the tiny optimisations often take up so much of our time that we cut the time spent on the really important things.

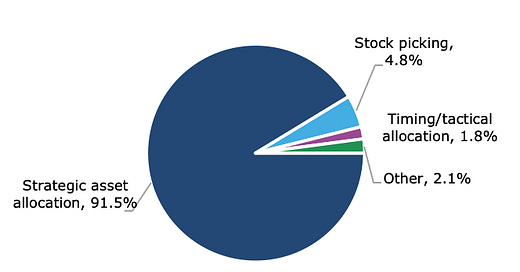

For example, we all know that the strategic asset allocation of our portfolios is one of the most important determinants of our financial success, yet even professionals spend remarkably little time each year thinking about these long-term decisions. Instead we agonise about tactical decisions, like how to position our portfolios for Brexit or the next Fed meeting. Or we ponder whether we should buy shares of Amazon or Microsoft.

The virtuous investor knows how to allocate her time properly to the things that matter and avoid spending too much time on things that don’t matter. So, without having spent too much time to optimise this list, here are some of the behaviours that I have observed in my career that really aren’t worth pondering about too much:

Small asset allocation weights. I cannot tell you how often I have been sitting in an investment committee meeting where the discussion focused on whether to increase the allocation to an asset class by 1% or not. I have seen strategic asset allocations of portfolios optimised with asset class weights to the precision of half a percentage point or more. And the obsession of many investors with tactical asset allocation where portfolio weights are shifted by a percentage point or so is beyond me. Every time I am in such a meeting, I want to scream at people: It does not matter! Imagine you think about allocating some of your portfolio to emerging market equities and you ponder if you should put 10% or 11% of your investments in that asset class (Similarly, you may wonder if you should overweight emerging markets tactically by 1%). Even if emerging markets outperform global equities by 10% over the subsequent twelve months or so, the return impact on your portfolio is a mere 0.1%. Meanwhile, the fees on the portfolio are often several times higher than that. And remember that this outperformance from emerging market equities is highly uncertain and could well go in the other direction since tactical asset allocation typically does not add value. As a rule of thumb, I stop discussing it if we talk about anything less than a 3% allocation.

Adding more and more exotic asset classes to a portfolio. How many marketing brochures have I seen where some fund shows the diversification benefits of, say aircraft leasing, by starting with a 60/40 stock/bond portfolio and then adding 5% of the fund to it. Who are you trying to fool? Surely, if an investor is even considering investing in something as exotic as aircraft leasing, she already has a lot of other alternative asset classes in her portfolio. And if you add aircraft leasing to such a diversified portfolio, the diversification benefits typically disappear or are so small as to make no practical difference. The same can be said for almost any alternative asset class. Once you have a few of them it will be really hard to add more value by adding a new asset class. Interestingly, the one asset class that has the biggest diversification benefits of all alternatives is the one that is most unpopular today: commodities.*

Tiny taxes. Taxes are an important factor to consider and getting your asset location right is a great way to enhance long-term performance. But I have seen so many investors try to optimise ineffectual taxes while ignoring the massive allocation differences in their portfolios overall. I am sure this is a global phenomenon, but in my experience, this is particularly an issue in Germany and Switzerland. A German adviser once told me that Germans are willing to pay two Euros to save one Euro in taxes and the current CumEx Files scandal in Germany certainly helps to reinforce that stereotype. In my personal experience, I have met clients in Switzerland who were obsessed with not paying stamp duties on their investments. In Switzerland, you have to pay a stamp duty of 0.075% as a private investor if you buy securities at a domestic exchange and a stamp duty of 0.15% if you buy securities abroad. The result is that these investors refused to buy international stocks and bonds because they did not want to pay the extra 0.075% in stamp duty. The end result was a portfolio of almost exclusively Swiss stocks, which meant essentially a concentration in food, pharmaceutical, and banking stocks but no technology, energy or utility stocks.

Choosing between two identical stocks. Stock picking can add tremendous value to your portfolio if you are skilled at it. But I have met too many people who asked me whether to invest in Roche or Novartis (if they were Swiss) or to invest in BP or Shell (if they were British). My honest answer: it doesn’t matter. In most cases these stocks behave almost identical and no investor cannot tell before the fact which one will outperform. Obviously, if BP gets hit by a major oil spill and Shell doesn’t the performance between the two will differ significantly, but in order to anticipate that you need to be good at something else altogether, namely predicting ESG risks. Once you have identified several stocks in the same industry that essentially have the same fundamental opportunities and risks, stop worrying and pick one. You can’t optimise beyond a sound fundamental analysis.

Forecasting with a decimal point. How many times have I been in a meeting where people argued whether US GDP growth next year will be 2.5% or 2.3%? IF I got a penny for each time, I would be richer than Jeff Bezos. And yet, it doesn’t matter at all, if the US economy grows at 2.3%, 2.5% or 2.7%, for that matter. What matters is if the US economy grows faster or slower than today and whether that is priced in the expectations of investors. If the US economy grows at 1.8% today and consensus expectations for next year are 2% growth as well, then growth of 2.3% or 2.5% doesn’t matter, because in both cases, risky assets like stocks should rally because growth accelerates more than anticipated. If the economy grows 1.8% today but consensus estimates for next year are 2.7%, then it does not matter if the economy grows at 2.3% or 2.5% because in either case it will be a disappointment and stocks will likely correct. The same growth can have a vastly different impact depending on the expectations priced into the market.

Forecasting with a decimal point, part 2. For all the stock pickers and equity analysts out there, who just got a big smile on their face when I criticised macroeconomists for their forecasts, let’s do the same with earnings forecasts…

Learn how to differentiate between the things that matter and the things that don’t and you will not only become a more virtuous investor, but you will suddenly become much more productive in life in general.

Share of portfolio variance explained by different policy decisions

Source: Brinson, Hood, and Beebower (1986).

*Note: If you are a professional asset allocator and you want to make your marketing people happy while not messing up your portfolio, combine the first two strategies and add an exotic asset class to your portfolio with an allocation of 1% or 2%. This way, you can tell your investors you are invested in that, but you don’t have to worry that it will destroy your performance if it all goes wrong.