The Virtuous Investor: Rule 2

Have confidence in your knowledge – even if it brings temporary losses

This post is part of a series on The Virtuous Investor. For an overview of the series and links to the other parts, click here.

“The next that thou go unto the way of life, not slothfully, not fearfully: but with sure purpose, with all thy heart, with a confident mind, and (if I may so say) with such mind as he hath that would rather fight than drink.”

Erasmus of Rotterdam

Once the virtuous investor has acquired the required knowledge in investment techniques, fees, market behaviour etc. it is time to put this knowledge into action. In fact, typically, the virtuous investor will build his knowledge in investments in a trial-and-error fashion, learning as he goes along. This is what we all do.

However, when putting our investment knowledge into practice we often abandon them at the first sight of trouble. A good investment strategy needs time to come to fruition and show its merits. Every asset allocator will tell you that you can only start to measure the performance of a strategy after five years or more. The higher the downside risks of a strategy (e.g. a pure equity portfolio) the longer the investment horizon needs to be. Yet even institutional investors typically assess their investment strategy after three years or less.

Individual investors are an even more impatient lot. In its Global Investor Survey 2019, Schroders asked 25,000 people in 32 countries how long they expect to hold an investment. Our chart shows that even in Japan, where investors were the most patient, the intended holding period for investments is 4.5 years. In Europe, it is typically around 3 years and in emerging markets it is typically 2 years or less. But these are self-reported expectations. In a previous job I had at a global wealth management firm we checked how long investors stuck to a specific asset allocation in their discretionary portfolio mandates. It turned out that investors changed strategy on average every 18 months! There is absolutely no way that an investment strategy can be evaluated after just one and a half years.

Expected holding period for investments

Source: Schroders Global Investor Survey 2019.

According to the 2016 survey from Schroders, it seems that institutional investors are a little bit more patient and expect to hold their investments about 4.7 years on average, but if you look at their deeds, not their words, they, too seem very impatient. Anne Tucker investigated the turnover of fund managers with three different metrics. Our chart below shows the average length of time that a stock stays in the portfolio of an actively managed fund. Note that this measure below is based on quarterly reported portfolio holdings by US mutual funds and thus excludes any stocks that have been bought and sold within a quarter. Even so, the average holding period for stocks was a mere 14 months, thought there is a trend towards longer holding periods visible in the chart.

Average holding period of stocks in active mutual funds

Source: Tucker (2018).

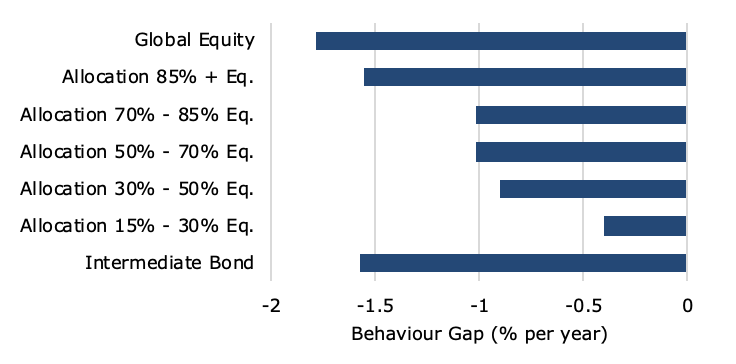

All of this buying and selling not only increases trading costs in a portfolio, it also introduces significant timing risk. If investments are sold and bought at the wrong time, the investor might end up missing rallies and experience a much lower return than a true long-term buy-and-hold investor. Of course, if the timing is right, the investor could also generate a much higher performance than the buy and hold investor if he manages to avoid drawdowns. Morningstar has for many years calculated the performance of the average investor and compared it to the performance of a buy-and-hold investor in the same fund. They call the difference between the performance of a buy-and-hold investor and the average investor the “behaviour gap”. The size of this behaviour gap over the ten years ending in March 2018 is shown in the chart below. Negative numbers imply that the average investor has had a worse performance than the buy-and-hold investor. Typically, the behaviour gap increases as investment strategies become more volatile. Investors in a defensive allocation fund with 15% to 30% allocated to equities lost about 0.4% per year relative to a buy-and-hold investor. Investors in global equity funds, however, lost 1.8% per year through ill-timed transactions.

Interestingly, if we enter the realm of pure bond portfolios, Morningstar shows rising behaviour gaps again with government bond funds, corporate bond funds and high yield bond funds showing behaviour gaps in excess of 1% per year. All of these numbers are large and lead to significant underperformance of the average investor vs. a long-term buy-and-hold investor.

Behaviour gap 2008 – 2018

Source: Morningstar.

No wonder that 51% of investors surveyed by Schroders were disappointed by their investment performance with the second most common complaint being that they should have remained invested for longer (the most common being a rather unspecific complaint about insufficient performance of the product). The survey also looked into the behaviour of investors during the short period of market volatility in the fourth quarter of 2018. Only 30% of investors did not change their portfolios while two out of three did make changes in response to the market volatility. Of these, one in five moved some of their investments in cash and 37% moved some of their investments in lower risk investments – thus missing out on the strong recovery in the first half of 2019.

Buy and hold is hard to do, but there are techniques that investors can use to “keep the faith” in their investment knowledge and their investment strategy. One of them is to put short-term market volatility into a long-term context as I have done here. I will write about another tool that links your portfolio to your investment goals in two weeks time when we talk about rule 4.