This post is part of a series on The Virtuous Investor. For an overview of the series and links to the other parts, click here.

“Moreover, if through infancy and feebleness of mind we cannot as yet attain to these spiritual things, we ought nevertheless to study not the sluggisher one deal, that at the least we draw as nigh as is possible.”

Erasmus of Rotterdam

Let’s face it, we all make mistakes, both as investors and in our lives. There is no shame in making mistakes, but there is shame in not wanting to get better at whatever you strive to do. If you want to be a great painter, you better paint as many paintings as you can. The first few are likely going to be rubbish, but over time, your skills will develop, and you will get better at it.

Does that mean you are going to be the next Leonardo da Vinci or Pablo Picasso? Probably not, because these painters had an exceptional amount of talent that only very few people have. But that talent needed to be exercised and practiced before it could come to full fruition. One of the fascinating things to do when you study artists is to look at their work in chronological order. You can do that for Leonardo with the help of Wikipedia here. What you will notice is that there are certain qualities of the art that come to the fore only gradually as the artist develops his skills and intuition. Leonardo painted the Mona Lisa thirty years after he painted Ginevra de’ Benci. Notice the difference?

Ginevra de’ Benci by Leonardo da Vinci (c. 1476 – 1478)

Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci (c. 1503 – 1516)

What is true for artists is true for investors as well. We all have to practice investing in order to get better. And just like most artists never will be as good as Leonardo, so too will most investors never be as good as Warren Buffett. But you can at least strive to become the best investor you can be.

There is one crucial difference between artists and investors. While we can choose to become an artist or not, everyone is forced to become an investor, whether they like it or not.

We live in a world where saving for retirement has increasingly been outsourced to individual investors, be it through the switch from defined benefit to defined contribution pension schemes, tax incentives for retirement savings like ISAs in the UK or IRAs in the US, or simply by the erosion of social security payments that no longer cover the necessary living expenses for many middle class people.

If we go beyond retirement savings, we need to save for a down payment on our first home, to pay for the education of our children and many other things. All of these life events force us to save money and invest it, often for many years. I put the word invest in italics in the last sentence because the easiest way to invest money is to leave it in a savings account and earn money market rates of return. In the past, that may have been sufficient but with today’s zero or negative interest rates in developed markets, this is no longer the case.

So, we are forced to invest our savings in stocks, bonds and other assets. And no matter how much you learn about investing through books or blogs like this one, it will not be the same as sticking your head out and investing your money in the real world.

One of the most satisfying things I get to do in my professional life is to work with younger analysts who have just left university or have very little practical experience as investors. It is very satisfying for me to see them develop their skills and help them do so. Amongst the most common observations I have with young analysts is that they tend to propose very risky trades. I remember one analyst proposing to invest in the Russian Rubel because it was cheap. My reaction to this proposal was to ask her if she had ever invested in the Russian Rubel herself? The currency might be cheap,but it is so volatile that most investors don’t have the stomach to stay invested for long enough to reap the rewards. You cannot get a feeling for volatility until you have invested your own money in risky assets and went along for the ride.

Practice is a necessity for investors, but unfortunately, practice is only half the ticket to better returns. The other half is to learn from past mistakes. And unfortunately, this is where most investors fail miserably. I have recently written a book about the seven most common mistakes investors make and devoted an entire chapter to the inability to learn from past mistakes and techniques investors can use to avoid this. The book will be published in February, so I won’t go into too much detail here.

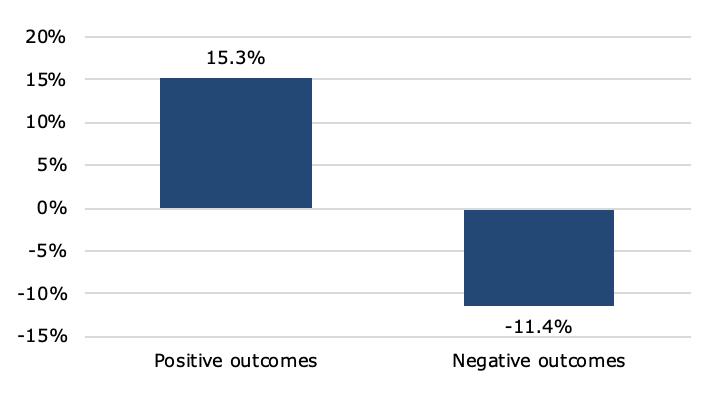

But I will say this: As investors we tend to forgetour past mistakes and remember our past successes. The chart below is taken from a recent study by Katrin Gödker and her colleagues at Maastricht University. They asked participants in an experiment to invest in a risky asset that could either have positive or negative outcomes. After a week, they went back and asked them how many times they had a positive outcome and how many times they had a negative outcome with their investments in the prior week. People on average overestimated the number of positive outcomes by 15.3% and underestimated the number of negative outcomes by 11.4%.

Biased recall of investment success and failures

Source: Gödker et al. (2019)

The virtuous investor is aware of this faulty financial memory and uses techniques to record investment decisions and learn from mistakes. The simplest technique I know of and that I use myself are investment diaries. In an investment diary, you record every investment decision you make with three short bullet points:

What decision did I make (e.g. I bought Russian Rubel at an exchange rate of $0.015 per Rubel)?

Why do I think this investment is going to make money (e.g. Rubel is undervalued by x%)?

What could go wrong (e.g. Rubel could devalue as oil price slips)?

These three bullet points in your investment diary give you a picture of your thinking. After a while (and I recommend doing this regularly) you can review past decisions and your thinking at the time. This way, you will start to understand where you made mistakes in your investment decisions and learn to avoid these mistakes over time. I admit, it is a long and tedious process that will improve your investment performance only gradually, but as with almost all things in life, there are no shortcuts. Becoming a good investor not only takes years of practice, it takes years of deliberate practice. And deliberate practice means not just doing things, but systematically reviewing past actions to learn from past mistakes and build on past successes.