This is not how yield curve inversions work

Over the last couple of weeks, I have seen several bloggers make a fuzz about the fact that the Treasury yield curve is steepening and no longer inverted. The general thrust (either stated explicitly or heavily implied) of these articles is that since the yield curve is no longer inverted, there won’t be a recession.

I am sorry, but that is not how logic works.

It is one of the most common logical fallacies to conclude that the inverse of “If A then B” is “If not A then not B”. “If the yield curve inverts, the US economy drops into recession” does not imply “If the yield curve does not invert, the US economy does not drop into recession”.

The correct contraposition of “If A then B” is “If not B then not A”. “If the yield curve inverts, the US economy drops into recession” implies “If the US economy does not drop into recession, then the yield curve does not invert”. Unfortunately, the last statement doesn’t make for a good story, so you never hear about that.

By the way, if you do not understand why “If A then B” implies “If not B then not A” then you need to brush up on your high school math (at least that’s where I learned that) or simply look up the explanation here. Unfortunately, the inability to do simple logic is widespread in the investment world and one of the reasons why so many pundits can safely be ignored.

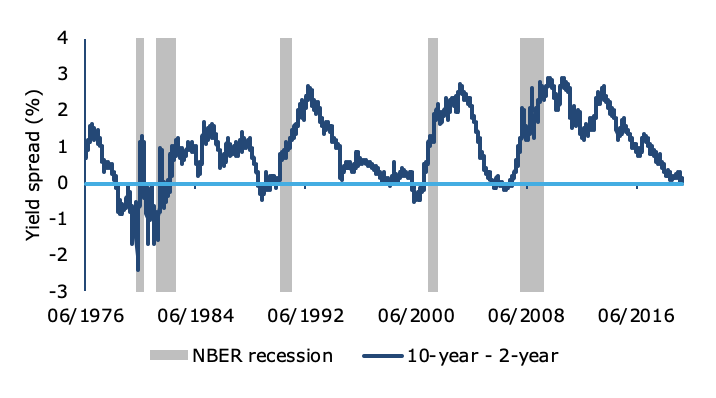

Let’s look at past yield curve inversions in the US to see what’s what. The chart below shows the difference between the 10-year and 2-year Treasury yield (10Y2Y) going back to 1976. As I have explained here, the 10Y2Y spread is my preferred measure of yield curve inversions because it has very few if any false positives.

Spread between 10-year and 2-year Treasury yields and US recessions

Source: FRED St. Louis Fed.

The eagle-eyed observer will notice that before almost every recession, the yield curve inverted and then steepened again, sometimes several times before the actual onset of a recession.

But for those of you like me who suffer from bad eyesight, I have summarised the data in the table below. For every recession since 1976, I have noted down the start date of the recession and the start and end date of the first yield curve inversion before the recession. I only counted yield curve inversions that happened at most two years before the onset of the recession. If a yield curve inversion ended before the onset of a recession, I checked if the yield curve dropped back into inversion before the recession. In order to avoid false counts simply because the yield spread was fluctuating around the zero mark, I only counted yield curve inversions as new inversions if they happened at least one month after the last inversion ended. As you can see, with the exception of the double-dip recession in the early 1980s, every recession of the last thirty years was preceded by yield curve inversions that were interrupted several times. A steepening yield curve and an interrupted inversion is rather the norm before a recession.

Interruptions of yield curve inversions before recessions

And how often did the yield curve invert and no recession followed within two years of the first inversion?

Zero.

There has not been a single false positive since 1976. If you ask me, I wouldn’t get my hopes up that this time is different, and we don’t get a recession in the US in the next one to two years.