Last Thursday, I wrote about why I think that investing to exploit vulnerabilities in markets or companies only works if one has a good idea of what could trigger a shift in market assessment and when that may occur. Today, I want to show how difficult it is to make money by investing in existing vulnerabilities with the help of a few numerical examples.

Let’s assume you have identified a vulnerability in the US stock market that if it materialises could lead to a bear market in the S&P 500. You don’t know how bad the bear market will be, so you look at three scenarios. First, a ‘regular’ bear market where the S&P 500 drops 25% and then recovers (you assume that you have great market timing and cash in at the bottom of the bear market…). Second, a severe bear market like we have seen it in the financial crisis in 2008 or after the tech bubble burst in 2000 when the S&P 500 dropped 50%. Third, a Great Depression-like bear market where the S&P 500 dropped 85%, something that we have seen only once in the history of the US stock market.

In order to benefit from this vulnerability, you have identified an investment that will cost you some money to hold but will pay off big time when the crisis happens. To keep things simple, I assume you buy a put option on the S&P 500 with one-year maturity so that at the end of the year the put option either expires worthless or pays off if the market drops.

For example, you could buy a put option with a strike price at the index level at the beginning of the year, so you hedge your entire investment. This put option will cost you about 5% of the market level and you can hold the rest in cash. The put option will pay off one-for-one if the market drops, so a 50% drop in the S&P 500 will give you a 45% return (1.45x your money when combined with the cash held elsewhere), etc. But maybe the vulnerability is something that can be taken advantage of with other assets that pay off much more. I have simulated different payoffs from 1.5x all the way to ten-baggers and hundred-baggers. Note though, that such ten- and hundred-baggers are extremely rare, so don’t make that your base case assumption. A realistic payoff for a levered bet on a vulnerability is 1.5x or less.

The table below shows the payoff of your investment for different likelihoods of the vulnerability to materialise (1%, 5%, 10%). Note also that I assume an event with a 10% likelihood will happen on average after ten years. It could well be that it happens after one year (10% chance) or not happen in the next 20 years (12% chance). In fact, the numbers show that it is more likely this event will not happen in the next 20 years than it will happen in the next year. So, you better have a very long time horizon when trying to exploit this vulnerability and investors who will not complain if you lose money every year for a decade or two before your investment pays off (good luck finding these investors).

As you can see, if you are trying to exploit a vulnerability that is very unlikely to materialise (say a default of the US or a once-in-a-century real estate or financial crisis) you are almost inevitably going to lose a lot of money compared to just investing in the market all the time and taking the hit when the crisis comes.

Even if the crisis is a once-in-a-generation crisis with a 5% chance of materialising like a very overvalued market (e.g. the tech bubble in the late 1990s) you are likely going to be worse off betting on the vulnerability than just staying in the market and riding the bubble. If somehow you found an investment that becomes a ten-bagger if the crisis hits, you need a 50% drop in the market or worse to break even. A normal bear market will not be enough.

And even in a once-in-a-decade vulnerability with a 10% likelihood of materialising will not necessarily be worth your time. With a simple put option that delivers a 1.5x payoff, you would need the worst bear market in US history to repeat itself before you broke even (and remember that I assume your timing in exiting the bear market or selling your put option is perfect).

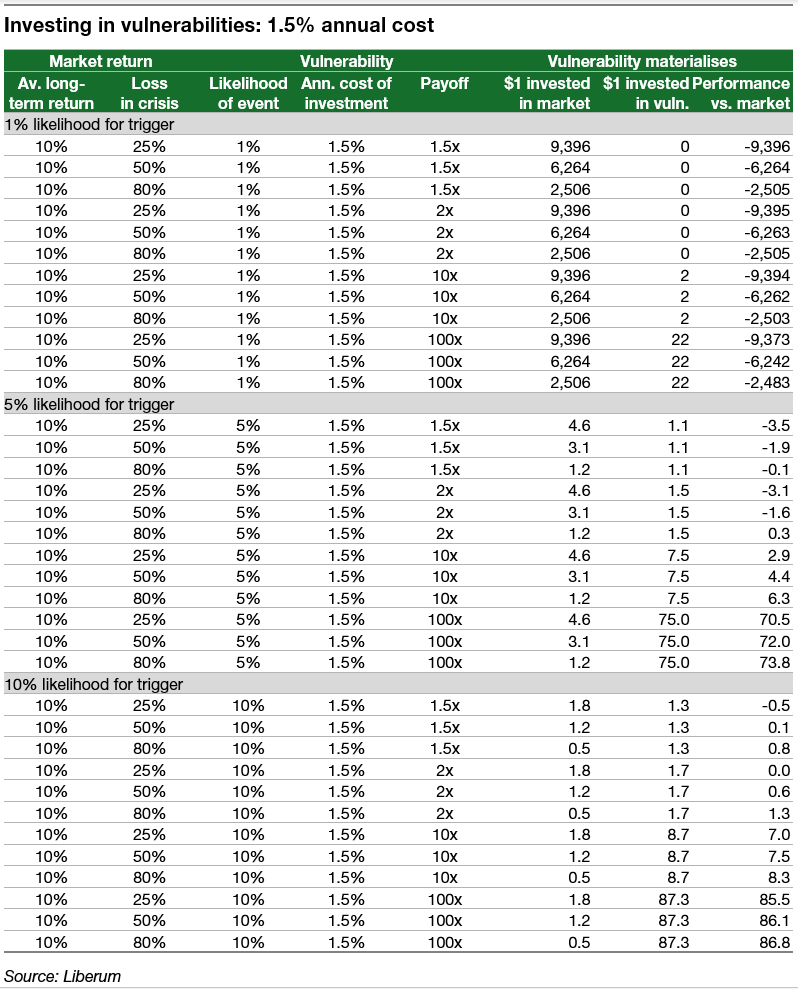

But a 5% cost every year may be too much. Maybe you can find an investment that only costs you 1.5% a year. This could be a 10% out-of-the-money put option where you take the first 10% of market losses yourself before your insurance kicks in. Or you invest in a bear market fund that charges you 1.5% per year and somehow manages to break even when the S&P 500 is up or down but pays off big time when the vulnerability materialises. No idea what such an investment could be, but I am sure you will be able to find some product marketers who will promise you a payoff like that.

With this, much lower, annual cost to bet on the vulnerability our payoff table looks like this:

Even with this much lower cost to bet on a vulnerability, you will need to have at least a 5% chance of the vulnerability materialising, the worst bear market in the history of the US repeating itself, and the investment to double in value before you are better off than being in the market all the time.

If the likelihood of the vulnerability materialising is 10% you will still need a 50% drop in the market and a return on your investment of 50% before you break even.

All of this goes to show why I tend to ignore vulnerabilities with a likelihood of materialising of 10% or less. It simply is not worth your time investing in these unlikely events. Even if the likelihood of the vulnerability materialising is 20% or more, you better have a major bear market and an investment that returns 30% or more when the market drops or it will not be worth your time.

This is why thinking about triggers is so important. It forces you to come up with an assessment of why a vulnerability should turn into a crisis, how bad the crisis will be if it materialises, and how much money you can make by investing in this vulnerability. All of these things have to work out at the same time or else you will simply be better off staying in the market and taking the hit when it eventually comes.

And in my experience, the vast majority of vulnerabilities in this world are so unlikely to materialise that there is no point in listening to Cassandras or paying attention to crisis scenarios. The maths is stacked against them. Being bearish only pays when you get lucky. And lucky bears are a rare breed.

"Lucky bears are a rare breed", exactly.

However, we are biased to think they are not rare and not even lucky -- we are inclined to think that folks like Roubini (who by the way, said in '22 a a global stagflationary recession was highly likely), and Taleb are a lot smarter than everybody else. Merely because of a few bulls-eyes!

That's the Taleb Paradox: he says we are all Fooled by Randomness; Warren Buffett just by coincidence did all the right things for a few decades (and lived long enough to enjoy the compounding effects), and yet we hope that Taleb *knows* better than everyone else how to make tons of money... by betting on catastrophies.