Normally, Fridays are reserved for lighter notes from the quirky corners of economics and finance research, but the July issue of the Review of Financial Studies had an article that I found mildly distressing. It looked at the relationship between stock market returns and violent crimes in the US.

With access to the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS), the researchers could track crimes in the US between 1991 and 2015. The more than 80 million incidents recorded in the database for that period contain a lot of details like the police precinct, the time of day of the crime, and the type of crime. Using the police precinct reporting the crime, the researchers could split the offenders into several income groups (i.e. whether crimes were committed in wealthier neighbourhoods or poorer ones), while using the type of crime data allowed researchers to differentiate between exterior crimes (e.g. robberies, traffic incidents, etc.) and domestic crimes.

Domestic crimes are predominantly committed by the residents of the home which together with the type of neighbourhood the home is in gives you an idea whether the offender is wealthy or not. Now add to the mix that only about 28% of US households own stocks and that these households tend to be in the wealthiest third of the nation by income, and you can try to assess if stock market returns have an impact on violent crimes.

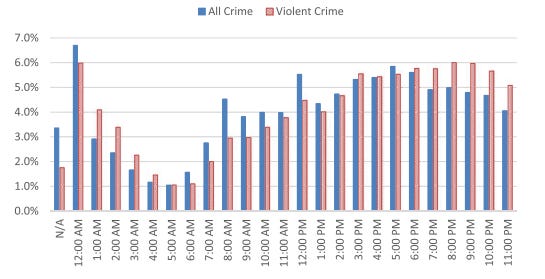

Violent crimes are mostly committed in the evening and at night

Source: Huck (2024)

The alarming finding of the study is that stock market returns are correlated with violent crime rates.

On average, violent crime rates increase on days with higher stock market returns. That sounds weird, but once you separate higher-income offenders from lower- and middle-income offenders it becomes clear what is happening. For low- and middle-income offenders, days with higher stock market returns are correlated with higher violent crime rates but that increase is not statistically significant. For high-income offenders, days with higher stock market returns are correlated with a statistically significant decline in violent crime rates. But there are of course many more low- and middle-income households than high-income households so the total violent crime rate shows a mild increase in violent crime on days with better stock market returns.

And of course, the reverse is true as well. Days with lower stock market returns are correlated with a statistically significant increase in violent crimes for high-income households. But not all violent crimes. Exterior crimes show no correlation while domestic crimes do show a correlation. In other words, the study shows a worrying correlation (and note that throughout this post I never used the word ‘causation’, only ‘correlation’) that indicates that on days with lower stock market returns men (and it is predominantly men) are more likely to attack their wives and children at home.

The effect is luckily not large. Extrapolated to the almost 400 million people living in the US, a one standard deviation drop in stock market returns leads to about 45 additional instances of violent crime, but it is a worrisome statistic, nevertheless. Especially if you think about the extreme days in stock markets during the pandemic panic in March 2020 or the height of the financial crisis in October 2008. In these extreme stress periods, daily returns were often four to six standard deviations below average indicating some 200 to 300 additional violent crimes as a result of the existential dread, stock market crashes can cause in investors’ minds.

Policework deters crime.

Friday hypothesis - during period of stockmarket volatility police officers are distracted by thier Robinhood accounts, financial news and reports, thus are not paying as much attention to their work and crime figures reflect this.

We could extend this to dates of sports fixtures which also (and this is a true fact) distract policemen, not by patroling near the events but by listening to the scores and putting bets on while they should be working.

fascinating! Never heard of such a connection, but it's not really a big surprise.

I suppose the correlation would be even more compelling in times where people are invested with a lot of leverage.

Not sure whether the correlation is linear. Were domestic violence incidents at end-March 2020 (while volatility was skyrocketing) so much more frequent than on normal "bad" days?

My superficial interpretation is that a certain percentage of folks are under high pressure quite often, and they just snap when exposed to a trigger. The trigger can be all kinds of stuff: Christmas, lousy weather, a bad day at the markets... So we do have a kind of correlation, but at the same time it's somewhat random.