No, I am not talking about elections, but about the famous Ben Graham quote (or was it Warren Buffet?) that “In the short-run, the stock market is a voting machine. Yet, in the long-run, it is a weighing machine”. This is still the case today, as a new study by Paul Geertsema and Helen Lu indicates.

The researchers wanted to know whether accounting variables like changes in assets and liabilities, profitability, or even simple measures like the change in outstanding stocks can predict stock market returns better than market-based measures like price momentum, size of the company, share price seasonality, etc.

To do this, they did something quite illuminating. They measured the predictive power of a battery of market-based metrics that have been shown in the literature to forecast future equity returns for all the stocks in the US between 1963 and 2022. Then they did the same for accounting-based variables.

But they didn’t just look at the typical forecast period of one month or one year and then rebalanced the portfolios every month or every year. Instead, they looked at the performance of stock portfolios based on these forecasting variables from one month ahead up to three years ahead. And, thankfully, they split the performance between a long portfolio and a short portfolio.

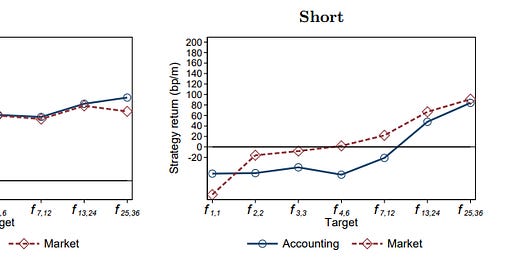

Here is the profitability of portfolios formed on market-based and accounting-based variables over time:

Performance of market-based and accounting-based forecasts over time

Source: Geertsema and Lu (2024). Note: f1,1 is the performance in the first month after the forecast was made, f4,6 in months four to six, etc.

Several things stand out in their results.

First, in the short term (forecast horizon of 1 to 3 and sometimes 12 months) market-based variables are much better at forecasting future stock performance than accounting-based variables. But over longer time frames (year two and year three after the forecast) accounting-based variables do just as good a job as market-based variables. In the case of the short basket of stocks to avoid, accounting-based measures tend to do even a better job than market-based measures.

Translated back to Ben Graham’s maxim, market-based variables effectively measure sentiment and how investors vote in the form of flows, etc. And in the short-term the market can be much better predicted by looking at how investors vote for or against a stock.

Second, in the long run, the fundamentals matter more and more. This is when investors weigh the long-term prospects of a company based on how the business is going rather than how the share price is moving. The longer the investment horizon, the more the market becomes a weighing machine.

Third, and this is not visible in the charts but an important finding, adding market-based measures to the accounting-based forecasts does not improve the long-term performance of the forecasts. And adding accounting-based measures to market-based forecasts does not improve short-term forecasts. The two work at different time frames and trying to mix them just muddles the water and in the worst case makes forecasts worse.

Fourth, accounting-based forecasts work better for larger stocks than small caps, presumably because larger stocks are subject to larger short-term mispricing as investors become overly excited about these stocks in the short run too afraid of touching them if they have underperformed in recent past.

Fifth, and something that isn’t mentioned in the research but strikes me as an important finding, forecasts with an investment horizon of 6 to 12 months don’t really work well, whether you use market-based or accounting-based variable. Yet, this is the forecasting period that most investors are interested in. Just think of the many forecasts strategists like me are constantly asked to provide for the next 12 months (in particular at the start of the year). And this is the investment horizon of tactical asset allocation, which apparently is still used by many private banks and actively managed multi-asset portfolios to ‘enhance returns’. But guess what? Tactical asset allocation is a bad idea that loses money almost all the time as has been shown time and again.

So please, stop trying to forecast the next 12 months and focus either on the next three months or the next three years. But my guess is, I will still be asked about the next 12 months and will continue to write annual outlooks and the like because that is what most people want. You can’t change human nature, I guess.

Let's reform the calendar so that a year is now 36 months.

..or 40 months if you want to it to be metric.

It will make us longer term thinkers, and another advantage is that by this measure I'm approaching my 16th birthday.

Intuitively, I like momentum-based strategies with a value „sanity check“. Unfortunately, this research appears to condemn this approach to the rubbish bin.

At the same time, it appears to support:

(1) long momentum strategies that re-balance the portfolio one every three months

(2) short strategies based on fundamentals

(3) ten-year return outlooks based on the CAPE of the market

What do you think?