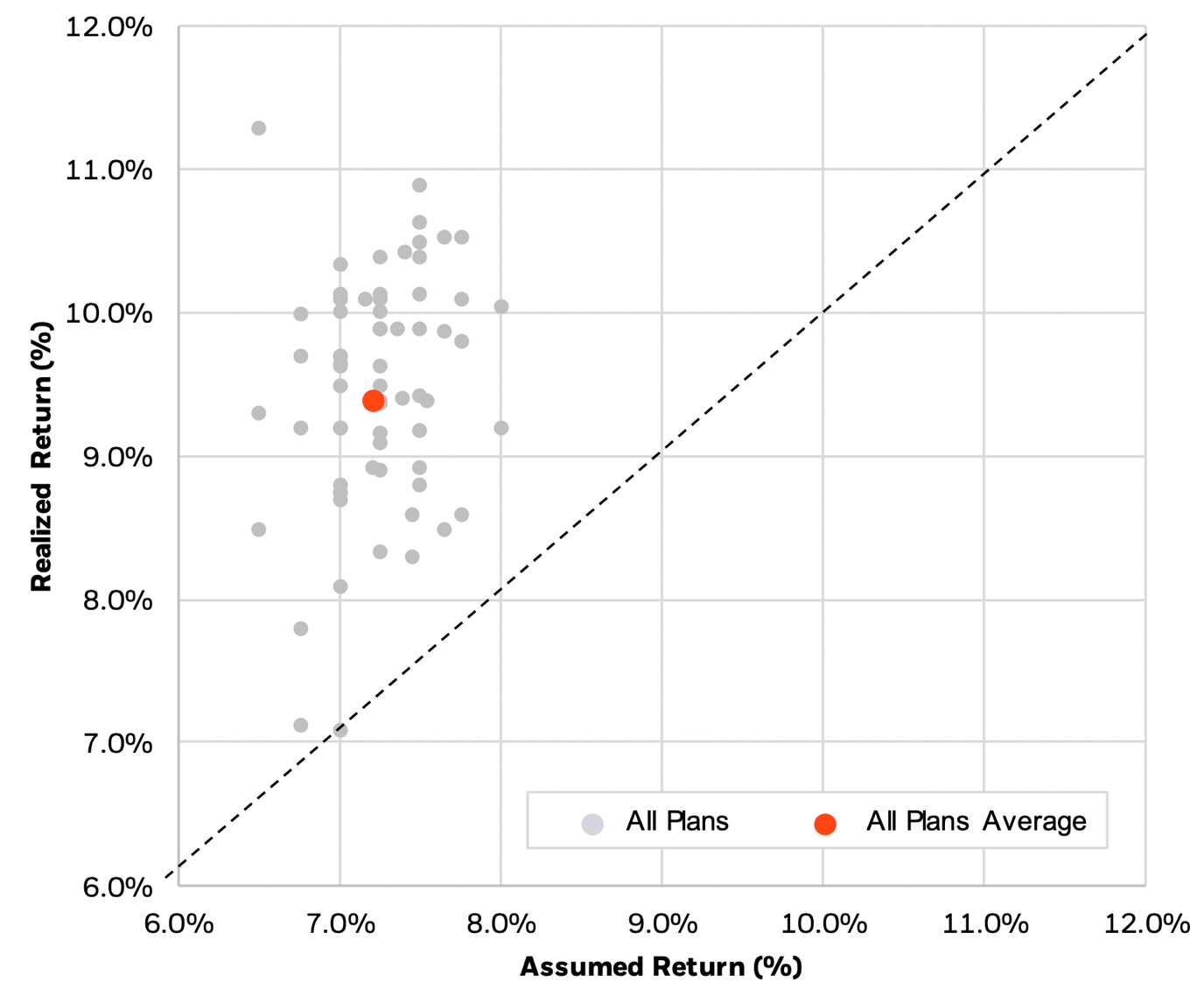

“Nobody puts baby in a corner” is the immortal line from Dirty Dancing, but it seems that by now, we have done exactly that to pension funds. For more than a decade, pension funds have been confronted with low expected returns for conventional assets and low interest rates in bond markets. And for more than a decade, they have got away with it thanks to booming equity markets. The chart below shows the expected returns of 69 US pension funds vs. the realised returns over the decade from 2010 to 2019 as analysed in a BlackRock study.

Realised vs. expected returns for 69 US pension funds during the 2010s

Source: BlackRock

The problem is that we cannot assume equity markets to go on booming forever. And note, that I am by no means bearish about equity markets this year or even on a ten-year basis. I think the mistake many observers make about equity market valuations is to assume that valuations have to decline to long-term averages. But I think it will be impossible to go back to normal interest rate levels we have seen before 2008 for a variety of reasons. And in a world of permanently low interest rates, equity valuations will settle around permanently higher valuation averages. Where these new averages are, I have no idea, but it certainly is above the 15 to 18 times earnings range many value investors hope to see again. Probably, the “new normal” is somewhere around 20 times earnings, but your guess is as good as mine.

Translating the asset allocation of pension funds into economic exposures one can see that pension funds require stable and ideally strong economic growth. It’s almost the only driver of returns in their portfolios.

Economic exposure of pension fund asset allocation

Source: BlackRock

Currently, we are still in the recovery from the pandemic so economic growth is strong, but interest rates are rising and economic growth will eventually slow down to more moderate levels in coming years. Which means that pension funds will start to feel some pain. How much pain will largely depend on equity market performance.

But in the US, though not in the UK or in Europe, equity markets are already fully valued so it seems unlikely that they will show another stellar decade as during the 2010s. How do pension funds get out of this corner? Here, investors need to be careful about the advice given by asset managers. Every asset manager has its own agenda. The folks at BlackRock recommend a combination of leverage and increased alternative investments, but that isn’t surprising since BlackRock is the world’s largest equity manager and has a very profitable (and high fee)set of alternative funds.

Looking through the expected returns for alternative assets, BlackRock assumes that private equity funds will achieve a return that is two thirds higher than the return of US small-cap equities (11.5% vs. 7% for US large and small-cap). Infrastructure investments are supposed to have a third higher returns than US equity while direct lending is supposed to have 50% higher returns than US equity. If you make these return assumptions, it is no surprise that the “optimal” portfolio is heavily geared towards alternatives.

While I am a fan of some alternatives (in particular infrastructure and CLOs), I think the history of alternative investments is one of lots of disappointment. The average performance of private equity over the long run is just 20% to 27% above the S&P 500 before fees. After fees, it is a lot smaller. And hedge funds have managed to underperform a simple 60/40 portfolio in the US every calendar year since 2002.

If you ask me, pension funds will have a day of reckoning sometime in the next decade where they will find out that all the alternatives in the world and all the leverage they may use will not be enough to generate the returns they expect to generate or need to generate. Pension funds would do well to think now about the measures they can take to be able to live with lower returns than the ones they achieved during the last decade. Hail Mary passes in asset allocation will not work all the time.

It’s time to think about the hard and painful measures that may not be too popular with beneficiaries. The longer these measures are postponed, the more painful they will have to be when they become inevitable. Just think of climate change. We could have put out economies on a more sustainable, less fossil fuel-dependent path at almost no cost if we had started in 1990. But we decided to wait for thirty years and now the costs of change are much higher. By relying on high equity market returns for a decade, pension funds have put themselves in a corner. Unfortunately, there will be no Patrick Swayze coming to rescue them.

What I find scary about pension funds current appetite for alternative investments is why are they investing in them really? Do they believe those investments are really going to provide superior returns despite the paucity of evidence for this or are they attracted to the opacity of valuations? It seems to me that with illiquid and difficult to trade investments there is the opportunity for the pension fund managers to make up pie in the sky valuations. This allows them to fiddle the returns they can claim to have made with made up numbers. This has already happened with superannuation funds in Australia. https://www.investmentmagazine.com.au/2020/04/more-pain-ahead-as-funds-writedown-assets/