It’s Fed Day (again) and while inflation is settling down in most countries, we are facing an increasing debate if the 2% inflation target most Western central banks aim for is achievable going forward. There is a case to be made that slowing gains from globalisation and persistent labour shortages in many sectors will push inflation systematically higher in the coming decade than what we used to have in the past. My research indicates that in the Eurozone and the UK, we should expect inflation to average somewhere around 2.5-3%, and in the US somewhere around 2-2.5%. But what do consumers think? Would they be willing to accept 3% inflation on a permanent basis?

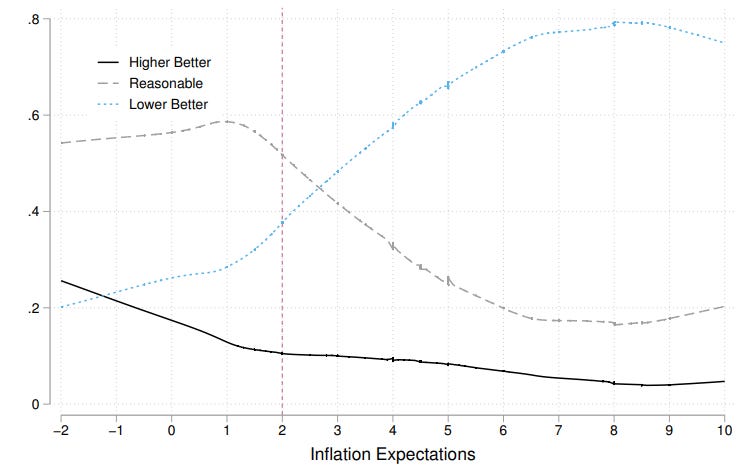

Lena Dräger and her colleagues asked consumers about their inflation preferences, their trust in central banks to achieve their inflation target, and other things. The key result is summarised in the chart below which shows for each level of inflation what share of consumers think that would be too high, too low, or about right.

Inflation preferences and inflation expectations

Source: Dräger et al. (2022)

Note first that no matter how low inflation is and even in deflationary times, the majority of people think that this would be a level that is too high or at best reasonable. This shows once again that the ordinary man or woman on the street does not understand inflation, something that is a major challenge for monetary policy as I have discussed here. Based on these survey results, the optimal level of inflation (if you ask the men and women on the street) would be 1%, but if it were 0% or even negative, people would not think of that as dangerous.

Second, note that once inflation surpasses 1%, views change quite quickly. The share of people who think inflation is too high and would better be lower starts to rise quickly, while the share of people who think inflation would be just right drops fast. This indicates that any change in the inflation target will likely trigger a significant public debate and will not be easy to communicate to the public.

And this is where the question about trust in central banks comes in. The survey found that people who have higher trust in central banks are more willing to accept a higher inflation target while people who do not trust the institution are less willing to do so. And given the track record of central bankers in the last couple of years, I dare say that trust in central bankers has eroded quite a bit, which means that opening a debate about a higher inflation target now is probably a very bad move. It would likely be soundly rejected by the public even though central banks (at least in my view) would do more damage trying to force an inflation rate of 2% or less on the economy than to let it average 2.5% or so. But if the public doesn’t trust institutions, changes to these institutions are very, very difficult to implement. And that is something that does not only apply to central banks.

Thank you so much for abbrevsting the Federal Reserve as "Fed" and not erroneously as "FED" as some do, as if it's an acronym such as the ECB.

I would say that central banks are the ones that do not know what inflation is :). Individuals experience inflation in direct terms: how living expenses move relative to their revenues (that is, their wages) to impact their welfare. I would postulate that the trend in a metric like the ratio of consumer prices / nominal wage index might be an effective way of measuring actual sensitivity of the populace in practical terms. The rate is too high or too low when it hurts. Studies asking citizens questions on what level of inflation (or deflation) is optimal seem a disingenuous exercise given that the wonks in the ivory towers cannot decide this amongst themselves [not to long ago in the US the target was assumed 0%, now it is 2%, and there is even a minority that calls for continued slow deflation].