Why are large companies so dominant?

The US, and in fact all industrialised markets have a megacap problem. The largest companies in a country or sector take up an ever-increasing share of the market, squeezing out smaller competitors. Just take a look at the profits relative to GDP of major US tech companies. This has led me and others to call for increased vigilance by regulators about anti-competitive measures by these companies and the possibility of a breakup of these dominant companies. But I am being challenged in my views by a new study by Spencer Kwon from Harvard and his collaborators.

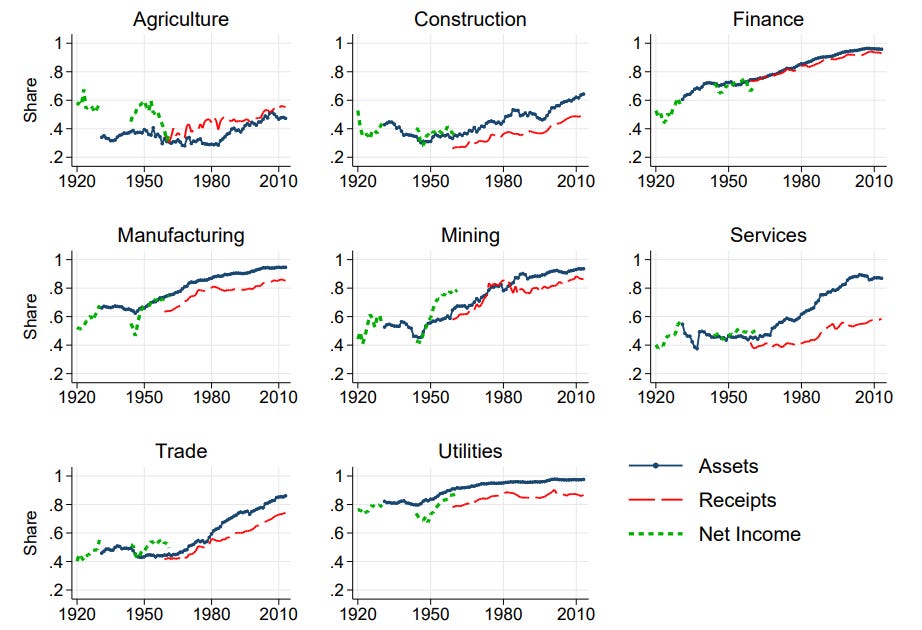

They looked at the concentration in a wide range of US industries over the last 100 years and found that in every industry there has been a persistent trend towards increased market share of the largest companies in each sector.

Market share of top 1% of companies by assets

Source: Kwon et al. (2023).

Note how in the chart above, the market share increases relatively steadily over the last century, indicating that the increased concentration of industries is not a result of lower tax rates or anti-competitive behaviour of companies in specific sectors. Instead, the research indicates that mechanisation and automatization allowed larger companies to take increased market share. Industry concentration increased particularly fast from the 1930s to the 1970s in the manufacturing, utilities, and mining industries when machines allowed to make workers more productive. Since the 1980s, service sectors like retail and leisure have seen the largest increase in industry concentration as services have become more automatised and less dependent on individual labour.

When did industries become more concentrated?

Source: Kwon et al. (2023).

This indicates that the key driver of industry concentration was economies of scale. Larger companies are better able to exploit the benefits of productivity-enhancing technologies. But in my view, if you dig deeper, another development stands out that enables larger companies to achieve these economies of scale: the ability to get access to capital at low cost.

As I have explained here, the secular decline in interest rates has been particularly beneficial to larger corporations which have easier access to capital markets and bank loans. This access to debt at ever-declining costs means that capital investments into productivity-enhancing technologies are more affordable and easier to make for larger companies than smaller ones. And this in turn means that economies of scale are increased over time.

Conversely, in times of rising interest rates and rising cost of debt, industry concentration should decline slowly. Look again at the first chart above. Note how during the 1970s, industry concentration remained stable or even slightly declined for all industries except finance. Obviously, that is no proof, but it seems a reasonable explanation. What it means, though, is that I need to revise my assumptions that the current industry concentration is excessive. It may be excessive from an ethical or normative point of view, but from a purely economic point of view, it isn’t. It simply is the result of a century-long trend towards increased industry concentration across all sectors.

The world you describe no longer exists. My client needs a VAT registration. More than 6 weeks ago we did the registration. Still no sign of the VAT number needed. Their sales are over the threshold so they are liable to pay the VAT from the date of the registration, BUT they cannot charge their customers VAT because they don't yet have a number. The solution from HMRC is to increase prices by 20 % whilst they wait for the VAT registration to be processed. - I kid you not - "You cannot include VAT on your invoices until you get your VAT number but you can increase your prices to account for the VAT you’ll need to pay to HMRC." You, Joachim, and I, are sophisticated and "process savvy" individuals, most small business owners are not. Personally this suits me because I have many clients who just cannot understand what they need to do to comply with the regulations. They pay me to advise them on getting it right. They shouldn't need to.

The UK. Simply opening a shop is a huge amount of paperwork and compliance with local council requirements. Add to that the tax admin and employment regulations which have to be satisfied BEFORE you can trade and I wonder why anyone would bother to attempt to start a business.