Low interest rates have all kinds of unintended consequences as we have found out over the last decade. They change investor behaviour and banks’ lending activities amongst other things. But there may even be a case to be made that low interest rates undermine market competition and lead to a rise in dominant companies in different industries.

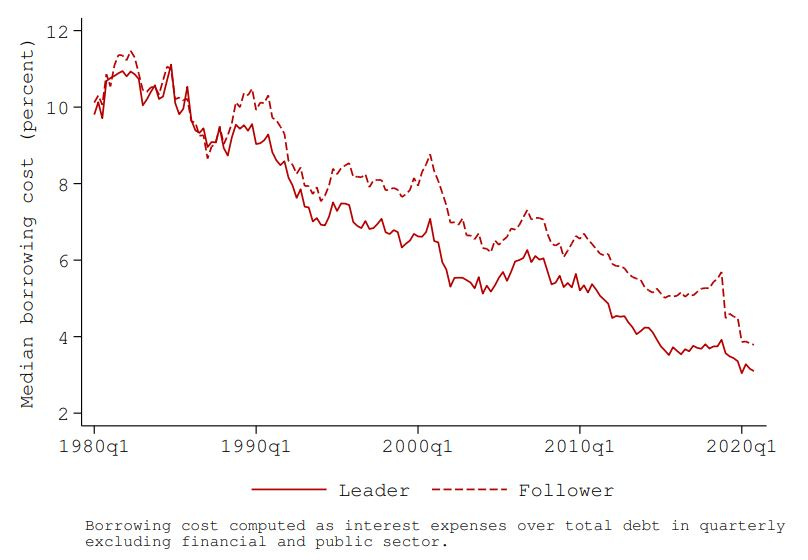

The chart below shows the average borrowing cost of market-leading companies and other companies in the same sector in the United States as calculated by Thomas Kroen and his colleagues at Princeton.

Average borrowing costs for market leaders and followers

Source: Kroen et al. (2021).

What seems to be going on is that as the level of interest rates declines, smaller companies that aren’t market leaders are subject to increasing risk premia for bank loans. This makes sense for lenders because, at very high interest rates, the extra risk in lending to a smaller company that may be driven out of the market is part of the overall compensation of the loan through high interest rates. But as interest rates decline, banks become more discriminating, charging smaller borrowers more than larger ones to compensate for the possibility that these smaller borrowers may have a harder time surviving in a recession.

But this difference in interest cost for market leaders and followers, on the other hand, allows market-leading companies to sustain lower borrowing costs and/or increase their balance sheet leverage to get more cash on hand. This cash can then be used to invest or purchase smaller competitors, which in turn increases the market share of these market leaders. The impact of these small differences in borrowing costs are amplified more in industries and sectors with large growth, where capturing market share is the best and sometimes only way for companies to become profitable. Think of social media and the tech space in general where there are large economies of scale and in fact, only the largest companies may ever be profitable while the small ones just burn cash until they die or are bought by larger competitors.

But of course, if the market leaders gain market share thanks to lower borrowing costs, that means that smaller companies in the industry become riskier borrowers for banks and banks increase the risk premia for these smaller borrowers. And so the cycle continues. The lower cost of capital for market leaders allows them to gain market share and that in turn increases their relative advantage in accessing low-cost capital. It’s a wonderful positive feedback loop and to be honest, I have no idea how, or when, it ends.

Very good piece and well observed. From the perspective of someone who spends most of their time advising or investing in SME companies, access to capital especially as these businesses transition through the scaling challenges of No Mans Land, is a key determinant of success. As a consequence smaller companies have to rely more heavily on equity or equity like sources of capital and/or increase operational leverage throughout the P&L structure. This requires financial fluency - a rarer commodity at the lower end of the spectrum - which in turn skews the distribution of value created and retained to the top 10% of SMEs in each industry sector, which is where they start to become interesting for small cap PE and so on. It ends - or at least the reset button is pressed - when the b/s leverage which prolonged access to lower rates of borrowing always bring with them turns around and bites them. For many enterprise sized businesses the misallocation of capital at this point in the cycle will cause high levels of stress down the road, but that may not be of much comfort to the bulk of the SMEs…Great piece.