Yesterday, I wrote about a study that compared essays written alternatively with the help of ChatGPT, Google or no tool at all. We found that people who write an essay with ChatGPT cannot remember anything about what they wrote. Meanwhile, humans who read essays written with the help of ChatGPT find them eerily formulaic and ‘artificial’. Today, I want to discuss a few findings on what is actually going on in our brains when we are writing essays with or without the help of ChatGPT.

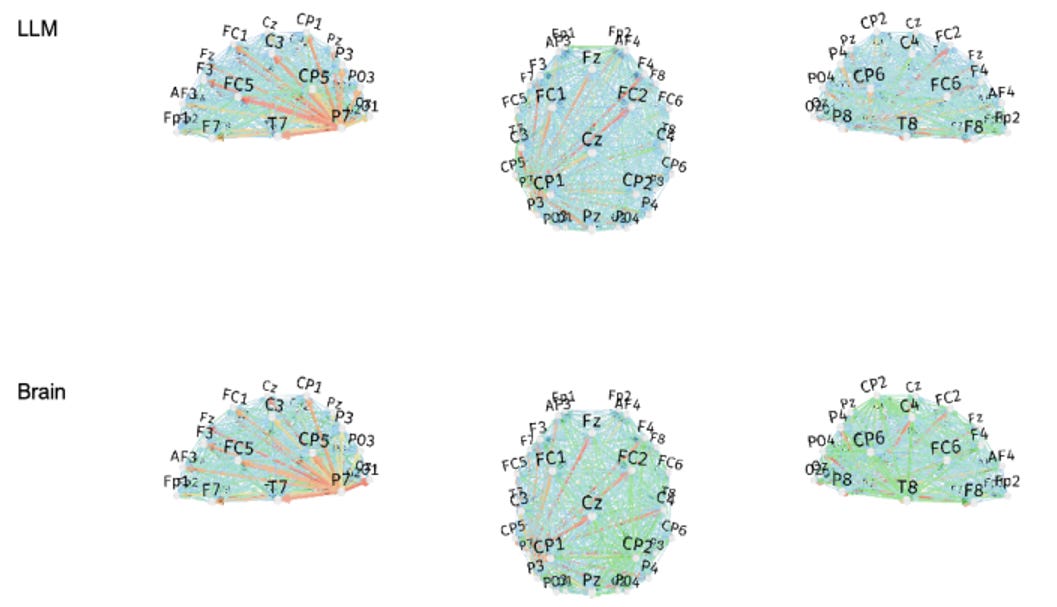

Below is an EEG chart of the alpha waves picked up from test subjects who wrote an essay using ChatGPT (top row) and those who had no help (bottom row). The colour-coding is such that blue shows low activation, green higher activation and yellow and red indicate the highest levels of activation. And if you don’t know what an alpha wave is (don’t worry, I didn’t know either), it is the frequency and pattern of electric activity associated with internal attention and focus, as well as creative tasks like brainstorming.

Alpha connectivity in EEG scans of people using ChatGPT (top) or no tool (bottom)

Source: Kosmyna et al. (2025)

The EEG results show that test subjects who used ChatGPT had lower brain connectivity and activity than people who had no tools to assist them. This supports the cognitive offloading theory of large language models. This theory claims that if we have access to ChatGPT and similar tools, we try to outsource as much of the hard mental labour to the tool in order to preserve energy for other tasks. And it seems as if people who used ChatGPT to write an essay really did shut off their brains, which also explains why they were afterwards unable to recall what they wrote in their essays.

Finally, another experiment the researchers did was to ask the volunteers who had used either ChatGPT or no tools to do the same task again, but with reversed roles. People who used ChatGPT for the first time were not provided with any tools to help them, whereas those who had no prior experience could now utilise ChatGPT.

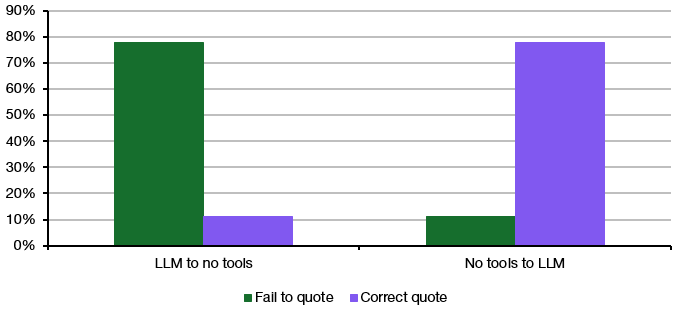

Going back to the results I showed yesterday about who was unable to remember any sentence from the essays they wrote versus accurately remember entire sentences, the chart below reveals an interesting finding. People who first completed the task without the help of ChatGPT and then were allowed to use ChatGPT remembered more of their essays, while people who used ChatGPT for the first time and then were stripped of the tool still couldn’t remember anything.

Essay recall among participants after switching access to support tools

Source: Kosmyna et al. (2025)

Indeed, brain scans of people who had access to ChatGPT but then had to write an essay without its help showed much higher brain activity if they were left to their own devices, but the connectivity in their brains was still lower than that of people who had practised essay writing without any help before. As a result, they were somewhat overwhelmed by the task of writing an essay without any tech help and had a harder time remembering what they wrote.

Indeed, one of the main results of the study seems to confirm the old adage of ‘use it or lose it’. If you don’t use your brain, it will slowly degrade, and your cognitive skills will decline. On the other hand, if you have trained your neural networks well and then start using ChatGPT and other tools, you can become better at the task at hand because you have two powerful engines that can work together rather than offloading exhausting work to a machine.

I’ll let the researchers have the last word:

“In conclusion, our analysis indicates that repeated essay writing without AI leads to strengthening of brain connectivity in multiple bands, reflecting an increased involvement of memory, language, and executive control networks. Prior use of AI tools, however, appears to modulate this trajectory […] These findings resonate with current concerns about AI in education: while AI can be used for support during a task, there may be a trade-off between immediate convenience and long-term skill development.”

I think the conclusion is a confirmation of what I had realized:

We are, in fact, at a crossroads. The first instinct — especially among those who did not live through the paper-to-digital transition — is to delegate knowledge entirely to AI: to turn to it when necessary and accept the first answer, whatever it may be. This becomes a disposable, as-needed kind of knowledge.

But the quality of AI’s answers depends on the depth of the questions. In the end, it becomes a dialogue with oneself — a way to draw answers out of our ability to ask the right questions.

Perhaps something similar has happened with keyboards versus handwriting; physically forming letters engages motor skills that aid memory, while typing just isn’t as memorable. That’s one of the reasons I still use a paper notebook in management meetings ... well, that and the fact that typing like a courtroom stenographer while avoiding eye contact feels incredibly rude.

Ancient orators used the method of loci https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Method_of_loci , walking as they recited to anchor their speeches in space and motion. I noticed the other day that when I re-wound and re-listened to a podcast segment, it brought me back to exactly where I had been walking the dogs a few hours earlier! I think all this is related; writing by hand or walking while reciting engages more of your sensorimotor system, which strengthens memory encoding. Embodied cognition, cross-modal reinforcement, and the ways we offload cognitive tasks to tools like keyboards or AI all shape how our brains encode and recall information.

Just as keyboards, calculators, and ChatGPT shift mental effort to tools, they also change how we learn. Offloading frees working memory but might reduce certain skills, such as fine motor memory or memorization techniques, unless consciously practiced. The method of loci works partly because it ties verbal information to spatial/motor memory. Similarly, handwriting connects visual, motor, and semantic processing. So these “old school” methods and modern tools may just be different ways of scaffolding memory. Optimistically, using tools such as ChatGPT doesn’t “dull” the brain, but just changes which neural pathways are strengthened.

Or maybe I’m just trying to remain positive and delude myself into thinking we’re not accelerating our societal slide! I think the band Missing Persons might have said it best: “It’s like the feeling at the end of the page, when you realize you don’t know what you just read.” https://youtu.be/BX86s8fHgkI